Political and Social Structure of Pre-1700 Europe: Feudalism, Manorialism

Contents

Political and Social Structure of Pre-1700 Europe: Feudalism, Manorialism

Introduction

The political and social structures of pre-1700 Europe, particularly during the medieval period (approximately 5th to 15th centuries), represented one of history’s most distinctive organizational systems. This era witnessed the development of feudalism and manorialism, interconnected systems that fundamentally shaped European society, governance, and economic life. The period marked a transition from the centralized authority of the Roman Empire to a decentralized, hierarchically-organized feudal framework that would dominate European society for centuries. Understanding this complex system requires examining its key institutions, the relationships between various social classes, and the legal frameworks that bound these classes together.

Feudalism: Definition and Core Characteristics

Definition

Feudalism, also known as the feudal system, represents a combination of legal, economic, military, cultural, and political customs that flourished primarily in medieval Europe from the 9th to 15th centuries. Historically, the term itself is a historiographic construct—a label invented long after the medieval period to describe the distinctive characteristics of that era, as feudalism was not conceived of as a formal political system by those who lived during the Middle Ages.

According to the classic definition established by medieval historian François Louis Ganshof (1944), feudalism describes a set of reciprocal legal and military obligations of the warrior nobility that revolved around three key concepts: lords, vassals, and fiefs. However, the broader definition articulated by Marc Bloch (1939) extends beyond the warrior nobility to encompass the obligations of all three estates of the realm—the nobility, the clergy, and the peasantry—all bound together by a system of manorialism, sometimes referred to as a “feudal society.”

The Oxford English Dictionary defines feudalism as “the dominant social system in medieval Europe, in which the nobility held lands from the Crown in exchange for military service, and vassals were in turn tenants of the nobles, while the peasants (villeins or serfs) were obliged to live on their lord’s land and give him homage, labour, and a share of the produce, notionally in exchange for military protection.”

Fundamental Principles

Feudalism was fundamentally characterized by the absence of centralized public authority and the exercise by local lords of administrative and judicial functions formerly performed by centralized governments and later resumed by them. The system was built upon several core principles:

Decentralization and Local Authority: Rather than centralized governance under a strong monarchy, feudalism fragmented authority among numerous local lords who exercised administrative and judicial control over their territories. This arose partly from the disorder and endemic conflict prevalent during the early medieval period.

Land-Based Economic System: Feudalism was fundamentally a way of structuring society around relationships derived from the holding of land in exchange for service or labour. The stability and security of land ownership formed the foundation of all social, economic, and political relationships.

Reciprocal Obligations: The feudal system was based upon mutual contractual obligations between lords and vassals. While the lord provided land (a fief), protection, and governance, the vassal promised military service, loyalty, and sometimes other forms of aid.

Military Organization: The primary purpose of feudalism was military. By granting fiefs to vassals, lords ensured a reliable source of military manpower necessary for defense and conquest.

The Feudal Hierarchy: Structure and Relationships

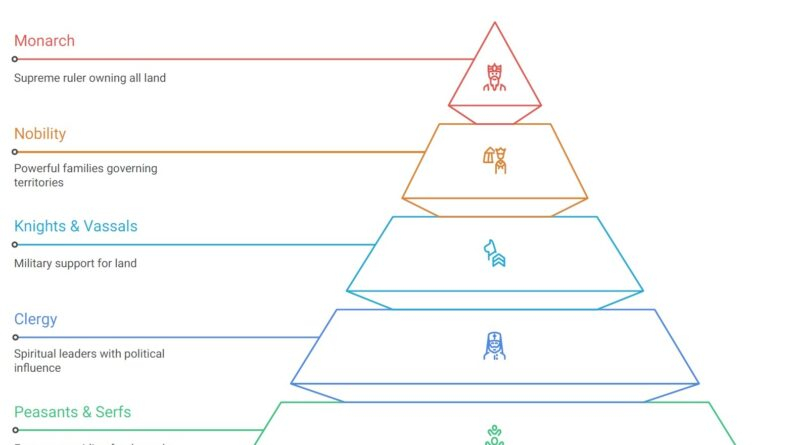

The Hierarchical Pyramid

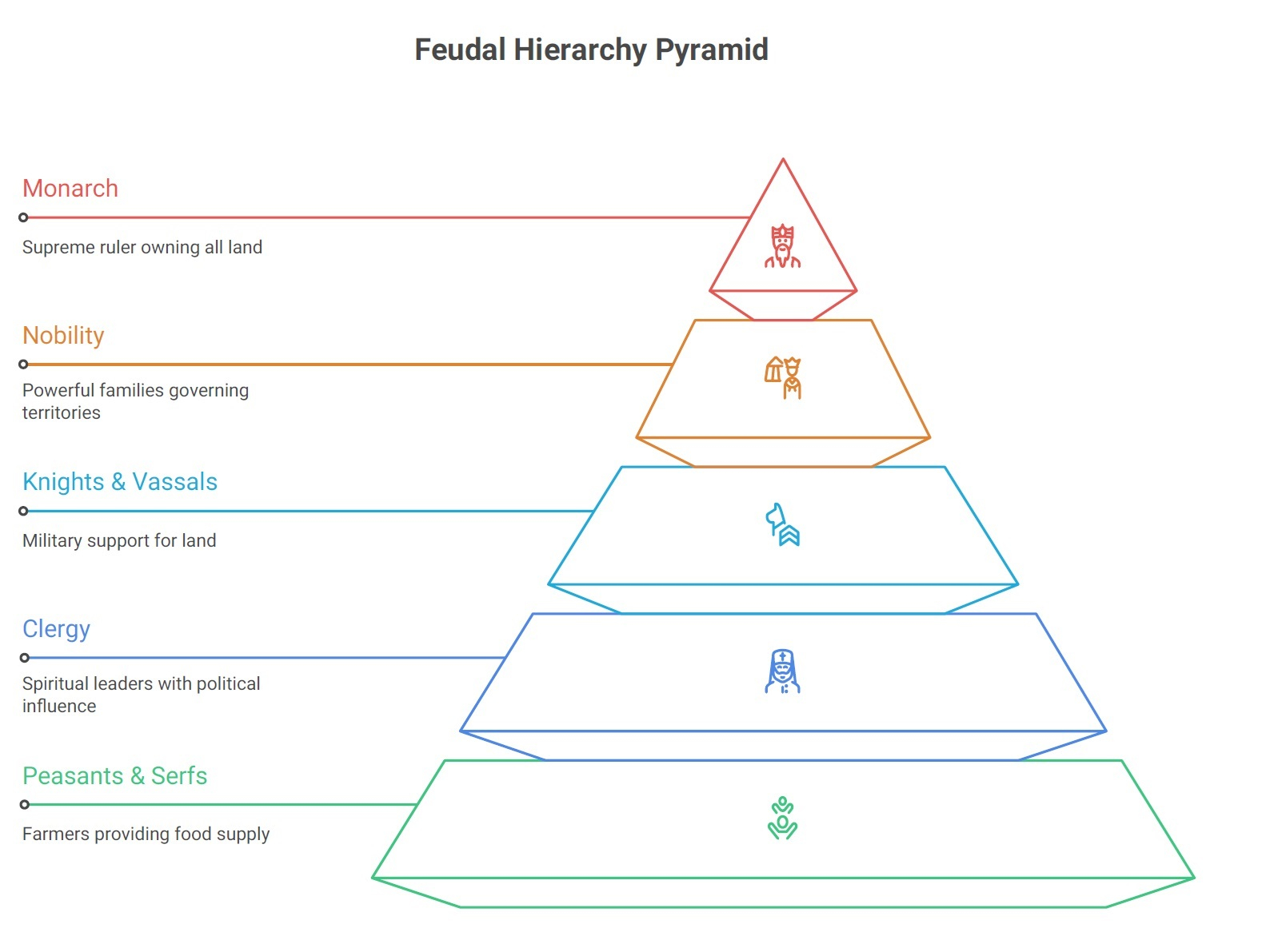

Medieval European feudal society was organized as a strict pyramid, with the king at the apex, followed by descending ranks of nobility, knights, clergy, and finally peasants and serfs at the base. Each level of this hierarchy contained specific rights and obligations:

The Monarch: The king occupied the supreme position, theoretically “owning” all land within his realm and presiding over administration and governance. According to the theory of feudalism, monarchs held all land in their kingdom and granted land to nobles in exchange for loyalty and military service. However, feudalism actually imposed restraints on the authority of the king, as monarchs had to rely on feudal lords for military support, which served as a counterbalance to royal despotism.

The Nobility: Nobles represented the richest and most powerful families in the realm. The king would divide his kingdom among the nobility, who operated particular portions of the kingdom, overseeing and governing them. The nobility held their lands from the Crown in exchange for military service and often held administrative positions. Within the nobility itself, there existed further hierarchical distinctions. Higher nobility included kings, dukes, and counts who held larger territories and more power, while lower nobility consisted of knights, barons, and landed gentry with smaller holdings.

Knights and Vassals: Even the land of the nobility was divided up into smaller parcels run by knights or vassals. Both of these groups traded military support for land in the local manors. As higher-ranking people, knights often presided over an entire manor, while vassals presided only over the land needed to support their families.

The Clergy: The clergy represented the third pillar of feudal society alongside nobility and peasantry. The clergy, consisting of religious leaders and institutions, held spiritual authority and wielded significant influence over both the ruling elite and the masses. The Church was granted land by monarchs and nobles in exchange for spiritual guidance and support. The clergy had its own hierarchy, with the Pope at the top, followed by bishops, priests, and monks and nuns. Higher clergy often came from noble families and held significant political influence, while lower clergy, such as parish priests, interacted more closely with the common people. At least three-quarters of the bishops and upper echelons of the medieval clergy came from the nobility, while most of the lower parish clergy came from peasant families.

Peasants and Serfs: At the bottom of the feudal hierarchy were the peasants and serfs, who were the poorest and had an extremely difficult lifestyle. Most people on a feudal manor were peasants who spent their entire lives as farmers working in the fields. The responsibility of peasants was to farm the land and provide food supplies to the whole kingdom.

The Vassal-Lord Relationship: Homage and Fealty

The relationship between a lord and vassal formed the personal backbone of feudal society. Before a lord could grant land (a fief) to someone, he had to make that person a vassal through a formal and symbolic ceremony composed of two parts: homage and oath of fealty.

The Ceremony of Homage: During homage, the vassal would appear before the lord bareheaded and without weapons, representing submission and non-aggression. The vassal would then kneel before the lord, clasping his hands as in prayer and extending them toward the lord—a position signifying total submission. The vassal would place his hands in those of the lord and declare himself “his man,” and the overlord would bind himself by kissing the vassal and raising him to his feet. This gesture sealed the personal bond between lord and vassal.

The Oath of Fealty: Following homage, the vassal swore the Oath of Fealty, vowing to be faithful to the overlord and to perform the acts and services due to him. Fealty denoted the fidelity owed by a vassal to his feudal lord. This formal procedure served to cement the personal relationship between lord and vassal, and after the ceremony the lord invested the vassal with the fief, usually by giving him some symbol of the transferred land.

The key characteristics of vassalage rested upon this unequal personal relationship between lord and vassal, cemented through the act of homage. In an age without much writing, this bond was based on trust and close personal connections, becoming a highly ritualized process with many witnesses—even ordinary people—and the pledge was often sealed with a kiss on the lips.

Fiefs: Land as Currency of Power

Definition and Purpose

A fief (also termed a feud or feudum) represents a parcel of land granted by a lord (suzerain) to a vassal in exchange for military service and loyalty during the feudal system in medieval Europe. The term “fief” derives from Old French, with roots tracing back to terms signifying “possession” or “to entrust,” immediately suggesting the inherent nature of the grant: a trust, a delegation of responsibility, and a promise of support in return for allegiance.

Critically, a fief was not allodial land (land held freely without obligations), nor did it represent true ownership. Rather, fiefs carried specific duties and obligations. The vassal did not own the land outright; he held it in return for services. This fundamental difference is crucial to understanding the nature of feudal society—the relationship was not merely about land; it was about reciprocal obligations and a structured society based upon a promise.

Functions of the Fief

The fief served multiple functions within feudal society:

Military Support: The fief wasn’t merely a land grant; it was the engine of the feudal machine. It provided the necessary resources to fulfill military obligations. Vassals, granted their fiefs, were expected to provide knights or soldiers to fight for their lord. Each fief, therefore, contributed to the military strength of the realm.

Economic Sustenance: The revenues generated from the fief provided the vassal with income necessary to sustain himself and his household. Using whatever equipment the vassal could obtain by virtue of the revenues from the fief, the vassal was responsible to answer calls to military service on behalf of the lord.

Manorial Administration: A fief was often a small section of a larger piece of land called a manor, and contained within it peasant populations who worked the land. The vassal administered the manor, overseeing peasant labor and collecting dues.

Transfer of Fiefs

Fiefs were not permanent personal possessions but rather grants conditional upon service. The vassal held the fief at the pleasure of the lord, and various conditions governed its transfer:

Inheritance and Relief: Feudal land tenure could be either free-hold if hereditable or perpetual, or non-free if it terminated upon the tenant’s death or at an earlier specified period. When a vassal died, his heir could inherit the fief, but inheritance was not automatic. The heir had to pay relief, a payment made upon transfer of a fief to an heir, to the lord for permission to succeed. Additionally, there was the principle of escheat, whereby the fief returned to the lord if the vassal died without an heir.

Wardship and Marriage: Feudal tenures were also subject to wardship, the guardianship of a fief belonging to a minor vassal, during which the lord could control the estate’s income. Additionally, lords could demand payment for the marriage of a vassal’s daughter, a practice called merchet.

Manorialism: The Economic-Social Framework

Definition and Nature

Manorialism, also known as seigneurialism or the manor system, was the method of land organization and labor control in parts of medieval Europe, notably France and later England, during the Middle Ages. It represented the political, economic, and social system by which the peasants of medieval Europe were rendered dependent on their land and on their lord.

The defining features of manorialism included a large, sometimes fortified manor house or castle in which the lord of the manor and his dependents lived and administered a rural estate, and a population of laborers or serfs who worked the surrounding land to support themselves and the lord. In general, Manorialism was a system of landholding common in Medieval Europe in which a feudal lord lived in and operated a country home (manor) with attached farm land, woodlands and villages. The land was for the use of the lord of the manor with surrounding homes in the farmland and villages that contained spaces for serfs (villein) who were tenants to the lord of the manor.

Importantly, manorialism and feudalism, while often discussed together, were distinct though interconnected systems. Feudalism was primarily a military and political system based on the vassal-lord relationship and fief grants, while manorialism was primarily an economic and social system centered on the manor and peasant labor.

The Manor as a Unit

The word derives from traditional inherited divisions of the countryside, reassigned as local jurisdictions known as manors or seigneuries; each manor being subject to a lord (French seigneur), usually holding his position in return for undertakings offered to a higher lord. The manor represented a self-sufficient economic unit designed to sustain both the lord and the peasant population.

Manorialism was characterized by the vesting of legal and economic power in the lord of a manor. The lord was supported economically from his own direct landholding in a manor (sometimes called a demesne—the lord’s personal farm), and from the obligatory contributions of the peasant population who fell under the jurisdiction of the lord and his court. These obligations could be payable in several ways: in labor, in kind (produce), or on rare occasions in coin.

The lord held a manorial court, governed by public law and local custom. This court served as the primary judicial authority for enforcing peasant responsibilities within feudal estates. Manorial courts maintained social order by addressing disputes and ensuring compliance with land tenure and obligations. Their functions included hearing cases related to unpaid rent, labor deficiencies, or unauthorized land use, settling disputes over land rights and obligations, imposing fines or penalties for non-compliance, monitoring labor services and payments due to lords, and ensuring legal adherence within the manorial community.

Manorial structures could be found throughout medieval Western and Eastern Europe: in Italy, Poland, Lithuania, Baltic nations, Holland, Prussia, England, France, and the Germanic kingdoms.

The Three Estates: Structure of Medieval Society

Medieval European society was organized into three functional estates, a concept sometimes called the “three-order” model of society:

The First Estate: The Clergy

The First Estate comprised the clergy, including bishops, priests, monks, and nuns. Their primary role was to administer spiritual affairs, provide religious guidance, and manage church properties. The clergy held considerable political and economic power, often exempt from taxes and wielding influence over the ruling class.

The Second Estate: The Nobility

The Second Estate consisted of the aristocrats and landowners—the nobility—who possessed considerable wealth and power, often monopolizing political offices and military command. This estate included all ranks of the feudal nobility, from the highest dukes and counts to the lowest knights.

The Third Estate: The Commoners

The Third Estate encompassed peasants, artisans, merchants, and urban workers, forming the bulk of the population. This diverse group contributed labor and resources to sustain the societal framework. They formed the economic foundation of society, yet possessed the fewest rights and privileges.

The concept of the three estates provided a framework for understanding medieval society’s hierarchical organization and served as a foundational framework for understanding historical power dynamics.

The Peasantry: Classification and Social Positions

The peasantry represented the vast majority of medieval European population, yet it was far from homogeneous. Medieval peasants occupied various positions within the social hierarchy, distinguished by their legal status, land holdings, obligations, and degree of freedom. Understanding peasant classifications is essential to comprehending the social structure of pre-1700 Europe.

Serfs and Villeins: The Unfree Peasants

Definition and Legal Status

A serf represented a peasant farmer bound to the land they lived on, usually from birth, and could be bought or sold along with that land (with important exceptions to be noted). In England, after the Norman conquest of 1066, an unfree tenant who held their land subject to providing agricultural and other services to their lord was described as a villein.

Critically, it is important to distinguish serfdom from slavery. Serfs categorically were not slaves—they represented a distinct legal and social condition. Unlike slaves who were absolute property with essentially no rights, serfs had rights and actually received something in return for their work. Serfs lived in their own houses, not in barracks like Roman-style slaves. Their spouses and children could not be sold away from them. No overseer with a club or knotted rope followed them about their daily chores. They could do as they wished with their surplus production, which at least some used for small-time trading.

During the medieval period, Europe transitioned from slavery to serfdom as the dominant system of labor and production. This transition began when slavery, particularly the chattel slavery of Roman times, gradually became replaced by the serfdom system as European kingdoms developed feudal structures. The coloni system of the late Roman Empire, where peasants were bound to land but retained certain rights, is believed to have been the original form of serfdom, which then became the dominant system of production in Medieval Europe.

Characteristics of Villeins

Villeins occupied the social space between a free peasant (or “freeman”) and a slave. A villein is classified as a class of serf tied to the land under the feudal system. As part of the contract with the lord of the manor, villeins were expected to spend some of their time working on the lord’s fields in return for land.

The status of a medieval villein changed somewhat over the course of centuries. However, what remained constant is the fact that a medieval villein worked on the land of the lord of the manor and his status was little more than a slave in terms of legal restrictions, though distinctly better than actual slavery. A medieval villein was a peasant who did not own any land of his own and had to till the land of his master for sustenance.

Villeins did not possess any land of their own and were thus dependent on their master for their sustenance. Villeins existed under a number of legal restrictions that differentiated them from freemen, and could not leave without their lord’s permission. Generally, villeins held their status not by birth but by the land they held, and it was also possible for them to gain manumission (freedom) from their lords. A medieval villein could be classified as a medieval peasant or more appropriately, a serf. Both serfs and villeins laboured on the land of their masters and could be sold to a new master along with the land.

The Villein’s Holdings and Commons Rights

A medieval villein was a peasant who worked his lord’s land and paid him certain dues in return for the use of land, the possession (not the ownership) of which was heritable. The dues were usually in the form of labor on the lord’s land. A medieval villein was expected to work for approximately 3 days each week on the lord’s land.

Besides holding farm land, which in England averaged about thirty acres, each medieval villein had certain rights over the non-arable land of the manor. A medieval villein could cut a limited amount of hay from the meadow, turn so many farm animals such as cattle, geese and swine on the waste, and take wood from the forest for fuel and building purposes. The holding of a medieval villein included a house in the village.

Restrictions on Villeins

Villeins were not freemen, and numerous restrictions governed their lives. They and their daughters were not allowed to marry without their lord’s permission. They could not move away without their lord’s consent and the acceptance of the lord to whose manor they proposed to migrate. Villeins did not enjoy any worthwhile social status and could be sold like slaves to new masters along with the land. A villein was thus a bonded tenant, so he could not leave the land without the landowner’s consent.

However, villeins were generally able to hold their own property, unlike slaves. In medieval England, two types of villeins existed—villeins regardant that were tied to land and villeins in gross that could be traded separately from land.

Advantages of Villeinage

Despite the restrictions, villeinage offered certain protections and advantages. In the Middle Ages, land within a lord’s manor provided sustenance and survival, and being a villein guaranteed access to land and crops secure from theft by marauding robbers. Landlords, even where they were legally entitled to do so, rarely evicted villeins because of the value of their labour. Villeinage was much preferable to being a vagabond, a slave, or an unlanded labourer.

Over time, both serfs and tenants came to enjoy greater security of tenure and gained further rights as English law developed. Manorial courts implemented a mixture of early common law and local variations—the “custom of the manor.” By the 14th century, tenants could enjoy greater security of tenure and could, for example, pass land on to their eldest son (subject to the discretion of the lord and payment of a fee).

Bordars and Cottars: The Lower Classes of Peasants

Below villeins in the social hierarchy were peasants of even lower status known as bordars and cottars (also spelled cottiers or cotars).

Bordars

Bordars, derived from the French border and recorded as bordari in medieval documents, were a class of peasant occupying a position below villeins. Bordars held barely two to three acres of land in strips at the edge of the village. The status of border or cottager ranked below a serf in the social hierarchy of manor. These marginal landholdings made them dependent on supplementary income from labor or other sources.

Cottars

A cotter, cottier, cottar, or similar variants represents a term for a peasant farmer occupying an even lower position than bordars. Cotters occupied cottages and cultivated small land lots. A cottar or cottier is also a term for a tenant who was renting land from a farmer or landlord.

The word cotter is often employed to translate the cotarius recorded in the Domesday Book (1086), a social class whose exact status has been the subject of discussion among historians. According to Domesday, the cotarii were comparatively few, numbering fewer than seven thousand people. They were scattered unevenly throughout England, located principally in the counties of Southern England.

Cottars had little more than the land on which their cottage stood. They either cultivated a small plot of land or worked on the holdings of the villani (villeins). Like the villani, among whom they were frequently classed, their economic condition may be described as free in relation to everyone except their lord.

Lower classes of peasants, known as cottars, generally comprising the younger sons of villeins or bordars in the British Isles, made up the lower class of workers. These marginal figures occupied the precarious boundary between peasant status and vagabondage, vulnerable to changes in economic conditions.

Free Peasants: The Independent Cultivators

Definition and Status

Free peasants, also known as free tenants or freemen, represented a distinct category of peasants who occupied a unique place in the medieval hierarchy. Unlike villeins, serfs, bordars, and cottars, free peasants enjoyed a surprising level of freedom and autonomy that belies the simplistic portrayal of medieval society.

Free tenants, also known as free peasants, were tenant farmer peasants in medieval England who occupied a unique place in the medieval hierarchy. They were characterized by the low rents which they paid to their manorial lord and were subject to fewer laws and ties than villeins.

One of the major challenges in examining the free peasants of this era is that no one single definition can be attached to them. The disparate nature of manorial holdings and local laws mean the free tenant in one region may well bear little resemblance to the free tenant in another. This definitional variability reflected the patchwork nature of medieval governance and the diversity of local customs.

Freedoms of Free Peasants

Unlike unfree peasants, free peasants enjoyed critical freedoms:

Land Ownership: Free peasants could own their land outright, free from feudal obligations. This represented a fundamental distinction from villeins who merely held land at the lord’s pleasure.

Freedom of Movement: Free peasants enjoyed freedom of movement and could leave their land if they chose to do so. However, villeins and other unfree peasants could not leave the land to which they were bound without their lord’s permission, and they also required acceptance from the lord of the manor to which they proposed to migrate.

Choice of Career: Free peasants could choose their profession and participate in local governance. They were not confined to agricultural labor but could pursue trades, crafts, or other occupations.

Marriage Without Restriction: Free peasants could get married without permission of their lord and could not be moved between estates against their will. This represented a critical distinction from unfree peasants, whose marriage choices required lord’s approval, often with fees involved (merchet).

Tax and Military Obligations: While free peasants had to pay taxes to the king rather than owing feudal services, they were subject to military service obligations, though often these could be commuted or avoided through payment.

Legal Definitions

Attempts were made by contemporary medieval scholars to set out legal definitions of freedom. One of the most notable was the treatise by Ranulf de Glanvill (written between 1187 and 1189), which stated that: “He who claims to be free shall produce in court several near blood relatives descended from the same stock as himself, and if they are admitted or proved in court to be free, then the claimant himself will be freed from the yoke of servitude.”

Another way to identify a freeman in the Middle Ages was to determine what kind of taxes or laws he had to obey. For example, having to pay merchet, a tax paid upon the marriage of a servile woman, was a key sign of being unfree. Free peasants did not pay such marriage taxes.

Types of Free Tenure

Free tenure encompassed several distinct types:

Socage: Primarily customary socage, the principal service of which was usually agricultural in nature, such as performing so many days’ ploughing each year for the lord. This represented one of the freest forms of tenure, with predetermined and limited services.

Fixed Rent: Freehold land was held primarily in return for a fixed rent, and its descent was not governed (or recorded) by the manor. However, freeholders were still subject to manorial jurisdiction in other respects, so that they do also appear in the records.

Leasehold: Others held leasehold land, usually for a year at a time in the medieval period, but later for longer terms.

Over time, there was a tendency over time for the rights of the lord to be eroded, and free peasants gained additional protections and security in their holdings.

Peasant Rights and Obligations

Rights of Peasants

Despite their subordinate position, peasants—both free and unfree—possessed certain rights within the feudal framework:

Right to Land and Livelihood: Peasants had the right to occupy and cultivate land, which guaranteed access to sustenance and protection from destitution and theft. While peasants did not own the land, they held hereditable possession rights that provided security.

Customary Protections: The concept of customary law or “the custom of the manor” provided peasants with established protections. Feudal law created certain predictability and prevented arbitrary lord behavior. Lords, even where they possessed legal authority to evict or punish peasants, refrained from doing so excessively because peasant labor was essential to the estate’s productivity.

Right to Own Property: Unlike slaves, peasants—even villeins—could own personal property, animals, and sometimes additional land beyond their primary holdings.

Limited Legal Recourse: Though of inferior status, peasants could bring grievances to manorial courts, which maintained records and applied consistent procedures.

Obligations and Duties of Peasants

The relationship between peasants and lords was fundamentally one of obligation. Peasants had several common obligations and duties toward their lords, which formed the core of their legal and social relationship:

Labor Services (Corvée): Peasants were often required to work on the lord’s land for designated days, performing tasks such as ploughing, harvesting, maintenance, cutting firewood, fixing the castle’s walls, and cleaning the moat. These labor services, known as corvée (from the French corvée), represented obligatory manual work performed without monetary compensation and were considered a fundamental duty of subordinate peasants.

The extent and nature of labour services could vary depending on local customs, the size of the estate, and the specific agreements between lords and peasants. Villeins were typically expected to work for approximately 3 days each week on the lord’s land, though this could vary by region and over time.

Payment in Produce and Rent: In addition to labor, peasants were responsible for paying various forms of rent and dues, which could be in the form of a share of their crop, livestock, or monetary payments. These financial obligations ensured the lord’s income and contributed to the stability of the property system. Payments often varied depending on local customs and the specific terms of tenancy.

Serfs farmed small plots of the lord’s land and were required to give a significant portion of their harvest to the lord. The serf was also required to give payments, on top of the payments of crops the lord already received at harvest time, at special times of the year—Christmas, Easter, and others.

Maintenance Duties: Peasants also had duties related to the upkeep and maintenance of manorial infrastructure, including roads, bridges, and mill facilities. They were required to maintain their holdings and could be fined by the lord if they did not.

Participation in Community Affairs: Peasants were expected to participate in community affairs and uphold customary laws enforced by manorial courts. These obligations reinforced the hierarchical social structure inherent in feudal law.

Special Taxes and Fees: The lord held several monopolies over his serfs, including controlling their access to flour mills, ovens, and wine presses. The lord could also influence a serf’s choice of spouse, often for a fee called merchet. Some villeins had to pay an annual fine called ‘capitage‘ if they lived in a place not owned by their lord.

Hereditary Nature: Being a peasant or a serf was typically hereditary. When a serf died, his son had to make a payment to the lord of the manor to succeed to his father’s holding.

Transition and Regional Variations

The End of Villeinage

The villeinage system gradually declined over time. In many medieval countries, a villein could gain freedom by escaping from a manor to a city or borough and living there for more than a year; but this action involved the loss of land rights and agricultural livelihood, a prohibitive price unless the landlord was especially tyrannical or conditions in the village were unusually difficult.

The villeinage system largely died out in England in 1500, with some forms of villeinage being in use in France until 1789. In medieval England, the system evolved into copyhold tenure, where by the 14th century “the royal courts protected [villeins] to the extent that he held tenancy at the will of the lord and according to the custom of the manor, so that he could not be ejected in breach of existing customs.” Copyhold tenure (abolished after 1925) saw the holder become personally free and paying rent in lieu of services.

Conclusion

The political and social structure of pre-1700 Europe, particularly the feudal and manorial systems that dominated medieval society, represented a complex hierarchical organization that provided both stability and constraint for millions of people across the continent. From the king at the apex of the feudal pyramid to the serfs at its base, every individual occupied a defined position with specific rights, obligations, and possibilities for advancement or decline.

Feudalism, fundamentally a system of military and political organization based on reciprocal obligations between lords and vassals, provided a framework for decentralized governance when centralized authority had collapsed. Manorialism, the complementary economic system, bound peasants to the land while providing them with guaranteed sustenance and protection. The classification of peasants—from free peasants with considerable autonomy to villeins with severely restricted freedoms, to bordars and cottars at the margins of survival—reflected the complex reality of medieval rural society.

Understanding these distinctions and structures is essential for comprehending pre-1700 European history, as the feudal and manorial systems shaped every aspect of life—from military organization and political power to economic production and daily social interactions. The systems were not static but evolved over centuries, gradually granting peasants increased security of tenure and rights even as the overall feudal framework eventually declined with the rise of centralized nation-states and commercial economies.

Discover more from Simplified UPSC

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.