Jainism

Contents

1. Jainism : origin

Jainism is one of the ancient Śramāṇa traditions of India, emerging as a spiritual and philosophical movement that rejected Vedic ritualism and Brahmanical authority. It is a non-Vedic religion—it explicitly rejects the authority of the Vedas and Vedic sacrificial practices, standing in direct opposition to Brahmanical Hinduism.

Distinctive Characteristics

Śramāṇa Tradition: Jainism belongs to the Śramāṇa (or Sramana) movement, meaning “seekers,” which began around 800-600 BCE as an offshoot of Vedic religion. The Śramāṇa movements rejected Brahmin authority and practiced an austere, ascetic path to spiritual liberation.

Ancient Roots: While traditional Jain accounts trace the religion through 24 Tīrthaṅkaras (spiritual teachers/ford-makers), scholars consider the first 22 as largely legendary or mythological. Parshvanatha (23rd Tīrthaṅkara) is the first Tīrthaṅkara for whom there is historical evidence.

Spiritual Lineage: The tradition of 24 Tīrthaṅkaras forms the spiritual foundation of Jainism. Mahavira (Vardhamana) is the 24th and most significant Tīrthaṅkara, who systematized and reformulated Jain teachings in their present form.

Historical Context

The rise of Jainism corresponds to the period around the 6th century BCE, a time of significant religious ferment in India marked by:

Opposition to formalized Vedic ritualism and the hierarchical Brahmanical system

Emergence of ascetic traditions emphasizing self-discipline and renunciation

Quest for spiritual liberation through personal effort rather than ritual performance

Universal accessibility of spiritual teachings, independent of caste and social status

Key Appeal: Jainism attracted followers due to:

Its ethical simplicity: Emphasis on non-violence (ahimsa), truthfulness, and renunciation

Accessibility: Used languages accessible to non-Brahmins (Prakrit rather than Sanskrit)

Democratic ethos: Welcomed people of all castes and social backgrounds

Logical consistency: Based on systematic philosophy rather than ritualistic authority

2. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND & SPREAD

The Sramana Movement Context

The Sramana tradition existed parallel to, but separate from, Vedic Hinduism. It represented:

A fundamental critique of Vedic ritualism and Brahmin monopoly over spiritual knowledge

An emphasis on asceticism (severe self-discipline and abstention from worldly pleasures)

Focus on personal liberation through ethical conduct and meditation

Rejection of the varna (caste) system, offering spiritual equality to all

Earlier Tīrthaṅkaras

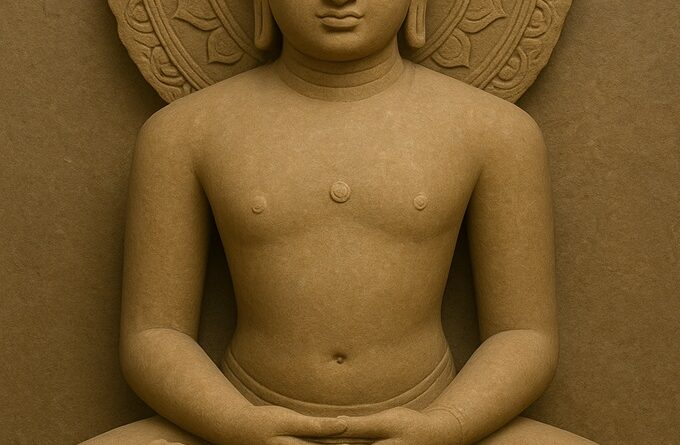

THE 24 TIRTHANKARAS WITH SYMBOLS AND ATTENDANTS

| S. No. | Name | Symbol | Color | Key Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Rishabhanatha (Adinatha) | Bull (Vrishabha) | Golden | First Tirthankara; founder of civilization |

| 2 | Ajitanatha | Elephant | Golden | Invincible one |

| 3 | Sambhavanatha | Horse | Golden | Auspicious one |

| 4 | Abhinandananatha | Monkey (Ape) | Golden | Worship; highly honored |

| 5 | Sumatinatha | Flamingo/Goose (Chakwa bird) | Golden | Wise; of good mind |

| 6 | Padmaprabha | Red Lotus (Padma) | Red | Lotus-bright; resplendent |

| 7 | Suparshvanatha | Swastika (Svastika) | Green/Golden | Good-sided; auspicious |

| 8 | Chandraprabha | Crescent Moon | White | Moon-bright; illuminating |

| 9 | Pushpadanta (Suvidhinatha) | Crocodile/Makara | White | Blossomed-toothed; bringer of religious duties |

| 10 | Shitalanatha | Shrivatsa (Sacred mark) | Golden | Coolness; peacefulness |

| 11 | Shreyamsanatha | Kalpavriksha (Wishing tree) | Golden | Good; auspicious |

| 12 | Vasupujya | Buffalo | Red | Worship with wealth/possessions |

| 13 | Vimalanatha | Boar/Pig | Golden | Clear; spotless; pure |

| 14 | Anantanatha | Falcon/Hawk (Shyena) | Golden | Endless; infinite |

| 15 | Dharmanatha | Vajra (Thunderbolt/Diamond) | Golden | Duty; righteousness |

| 16 | Shantinatha | Deer/Antelope (Mriga) | Golden | Peace; tranquility |

| 17 | Kunthunatha | Goat (Chagala) | Golden | Heap of jewels |

| 18 | Aranatha | Fish/Nandavarta | Golden | Division of time |

| 19 | Mallinatha | Kalasha (Water pot/Pitcher) | Blue | Gender Controversy: Svetambara consider female (Malli Devi); Digambara consider male |

| 20 | Munisuvratanatha | Tortoise (Kurma) | Black | Of good vows; observing five vows |

| 21 | Naminatha | Blue Lotus (Nila Padma) | Golden | Bowing down; eye-winking; respectful |

| 22 | Neminatha | Conch Shell (Shankha) | Black | The rim whose wheel is unhurt |

| 23 | Parshvanatha | Serpent/Snake (Naga) | Blue/Green | Lord serpent; historical Tirthankara (~877-777 BCE) |

| 24 | Mahavira (Vardhamana) | Lion (Simha) | Golden | Great hero; most recent historical figure (599-527 BCE) |

Parshvanatha (23rd Tīrthaṅkara):

Traditionally preceded Mahavira by about 250 years (c. 877-777 BCE, estimated by tradition; c. 872-772 BCE per scholars)

Established the Chaturyama Dharma (Four-fold Restraint):

Ahimsa (Non-violence)

Satya (Truthfulness)

Asteya (Non-stealing)

Aparigraha (Non-possession)

Allowed monks to wear upper and lower garments

Historical Significance: First Tīrthaṅkara with historical evidence; worshipped with serpent symbolism due to legends of snake salvation

His teachings formed the foundation that Mahavira would later reform and expand

Royal Patronage and Diffusion

Mauryan Period: Jainism received significant royal support; various kings patronized the religion

Bimbisara and Ajatashatru: King Bimbisara of Magadha and his successor Ajatashatru were notable patrons of Mahavira

Chandragupta Maurya: Later associated with Jainism during the period of migration and sect formation

Regional Spread: Jain monks and nuns (sādhus and sādhvis) wandered extensively, preaching through debates and personal example, facilitating the spread of Jainism across India

3. LIFE OF MAHAVIRA (599-527 BCE)

Mahavira (meaning “Great Hero”) was born as Vardhamana (meaning “Increaser of Prosperity”). His life trajectory exemplifies the Jain path of renunciation and spiritual achievement.

Birth and Early Life

Birth: Born in Kundagrama (near Vaishali), a kingdom in present-day Bihar

Parents: King Siddhartha and Queen Trishala

Time Period: Traditionally dated 599-527 BCE (lived approximately 72 years)

Birth Circumstances: According to Śvetāmbara tradition, Trishala had auspicious dreams predicting the birth of a spiritual leader: white elephant, Goddess Lakshmi, full moon, rising sun, lotus pond, and blazing fire

Upbringing: Raised in luxury and royal comfort with uncommon wisdom and spiritual sensitivity; displayed rare compassion and bravery from childhood

Family Background: Mahavira’s parents were followers of Parshvanatha, suggesting early exposure to Jain philosophical ideas

Renunciation and Ascetic Life

Marriage: Though he practiced non-attachment even before formal renunciation, Mahavira married (tradition suggests at his parents’ insistence to show filial obedience) to a woman named Yasoda

Age of Renunciation: At age 30, after his parents’ death, he left household life publicly during daylight hours—emphasizing his action was a conscious, deliberate choice with family support, not covert escape

Ascetic Practices (12 years of extreme austerities):

Lived in the open without shelter

Practiced complete nudity (significant for Digambara tradition)

Ate only once daily or fasted for extended periods

Endured extreme physical hardship without resistance

According to the Acharanga Sutra (oldest Jain scripture): “Once when he sat in meditation, his body unmoving, they cut his flesh, tore his hair, and covered him with dirt… Undisturbed, bearing all hardships, the Venerable One proceeded on the path of salvation.”

Attainment of Omniscience

Duration: After 12 years of asceticism, in his 13th year (traditionally at age 42), Mahavira attained Kevala Jnana (also called Kaivalya or Kevalajnana)

Meaning: This represents the complete and perfect omniscience—the burning away of all obscuring karma, particularly the ghati karmas (harming karmas) that obscure the soul’s true nature

Significance: Mahavira achieved the state of infinite knowledge, unobstructed by any karmic matter, achieving absolute clarity and perfect perception of reality in all its aspects

Spiritual Status: He became a Jina (Conqueror)—one who has conquered all inner passions and attachments

Ministry and Teaching (30 years)

Duration: For approximately 30 years until his death, Mahavira preached actively

Geographic Reach: Wandered extensively through regions including Kosala, Magadha, and other territories in North India

Royal Support: Enjoyed patronage from powerful monarchs, particularly:

King Bimbisara of Magadha

Ajatashatru (Bimbisara’s successor), who became a devoted follower

Monastic Establishment: Founded a monastic order of monks and nuns, establishing a structured religious community

Teaching Method: Taught through discourse, debates with rival sects, and personal example

Death and Liberation

Place: Died at Pava (near Rajgriha/Patna, in present-day Bihar)

Age: At age 72 (according to tradition)

Attainment: Achieved Moksha (liberation)—final release from the cycle of birth, death, and rebirth

4. MAHAVIRA’S PHILOSOPHICAL FRAMEWORK

4.1 Goal of Life: Moksha and Kaivalya

The ultimate objective in Jainism is Moksha (liberation) or Kaivalya (aloneness/isolation of the soul):

Meaning: Complete freedom from the cycle of birth (janma), suffering (dukha), and death (mrityu)

State of Liberation: A soul in moksha exists in a state of infinite knowledge, infinite perception, infinite power, and infinite bliss—the intrinsic qualities of the soul freed from all karmic bondage

Path: Achieved through the Ratnatraya (Three Jewels) working in harmony

4.2 The Three Jewels (Ratnatraya)

These form the core ethical and spiritual framework of Mahavira’s teachings:

Samyak Darshana (Right Belief/Right Faith)

Correct understanding of the true nature of reality

Proper faith in the teachings of the Tīrthaṅkaras

Recognition of the fundamental truths (tattvas) of Jain philosophy

Foundation for the other two jewels

Samyak Jnana (Right Knowledge)

Understanding the true nature of the soul (jīva) and matter (ajīva)

Comprehending the process of karma and bondage

Knowledge derived from multiple means (pramanas) and viewpoints (nayas)

Not merely intellectual knowledge but experiential wisdom

Samyak Charitra (Right Conduct)

Ethical living through the observance of vows

For monks/nuns: strict adherence to the Pancha Mahāvratas (Five Great Vows)

For laypeople: practice of Anuvratas (Lesser Vows)—modified versions suitable for householders

Right conduct purifies the soul of karmic matter and facilitates liberation

Integrated Approach: These three work together synergistically—right belief guides right knowledge, which motivates right conduct, creating a complete framework for spiritual progress.

4.3 Metaphysics: Jīva and Ajīva

Jainism presents a dualistic metaphysics fundamentally different from monistic Hindu philosophy:

Jīva (Soul/Living Entity):

The conscious, sentient principle

Exists independently of matter

Possesses qualities of knowledge, perception, power, and bliss in their inherent form

Found in all living beings—humans, animals, plants, and even seemingly inanimate objects (according to some interpretations)

Each jīva has capacity for suffering (dukha) and has agency in spiritual development

Universal Sentience: Jainism teaches that all beings possess jīva; capacity for suffering extends even to single-sensed organisms, plants, and elemental forms of life

Ajīva (Non-Soul/Matter):

The insentient, non-conscious principle

Includes all material substance and time

Does not possess consciousness or perception

Exists as both gross (visible) and subtle (invisible, including karmic matter) forms

Karma as Subtle Matter:

In Jainism, karma is conceptualized as subtle matter—actual particles that bind to the soul

Karmic matter obscures the soul’s inherent qualities and perpetuates the cycle of rebirth

The soul becomes bound when karmic particles attach themselves due to passions and improper actions

Bondage: Results from the influx (āsrava) of karmic matter attracted by emotional attachment, anger, greed, and delusion

5. FUNDAMENTAL DOCTRINES: KARMA AND LIBERATION

5.1 The Theory of Karma

In Jain philosophy, karma is not merely a law of moral causation but represents actual karmic matter that binds the soul:

Key Principles:

Āsrava (Influx): The flow of karmic matter toward the soul, caused by:

Passions and emotions (anger, greed, pride, delusion—the four kasayas or “sticky substances”)

Improper actions and intentions

Attachment and aversion

Bandha (Bondage): The actual binding of karmic matter to the soul through:

Duration (length of bondage)

Intensity (strength of karmic effects)

Type (nature of the karma)

Samvara (Stoppage): Prevention of new karmic influx through ethical conduct, right belief, and spiritual discipline

Nirjara (Wearing Away/Exhaustion): Elimination of existing karma through:

Ascetic practices and austerities (tapas)

Proper conduct and self-discipline

Meditation and self-purification

5.2 Eight Types of Karma (Prakrti)

Jain philosophy classifies karma into eight primary categories, grouped into two major divisions:

Harming Karmas (Ghātiyā Karmas) — Directly obscure the soul’s inherent powers:

Darśhanāvarṇiya (Perception-Obscuring Karma)

Obscures the soul’s faculty of perception

Prevents direct intuitive knowledge

Gyanāvarṇiya (Knowledge-Obscuring Karma)

Obscures all forms of knowledge

Sub-types affect sensory knowledge, scriptural knowledge, clairvoyance, and telepathic knowledge

Antarāya (Obstacle-Creating Karma)

Creates impediments to spiritual and worldly accomplishments

Blocks the soul’s energy and capability

Mohanīya (Deluding Karma)

Causes delusion and false beliefs

Generates attachment and aversion

Divided into passional deluding karma and belief-system-deluding karma

Sub-types based on intensity: mild, moderate, intense, and extreme

Non-Harming Karmas (Aghātiyā Karmas) — Determine physical and mental circumstances:

Nāma Karma (Body/Status-Determining Karma)

Determines the type of body and physical form

Causes diversities among jīvas (123 sub-types)

Includes four states of existence: celestial, human, animal, and infernal

Gotra Karma (Lineage-Determining Karma)

Determines social status, family lineage, and social position

Creates high status (upper castes, royalty) or low status (lower castes, servitude)

Āyū Karma (Lifespan-Determining Karma)

Determines the duration of life in each birth

Fixed once bound; cannot be altered once activated

Vedanīya Karma (Feeling-Producing Karma)

Produces pleasant and unpleasant sensations

Causes experience of joy and sorrow

Source of interruption of the soul’s natural bliss

Significance: Understanding karma classification helps practitioners identify which karmas to exhaust through specific practices.

5.3 The Process of Bondage and Liberation

Bondage Mechanism:

Four passions (kasayas) act as “sticky substances” causing karma to attach to the soul:

Krodha (Anger)

Lobha (Greed)

Mana (Pride)

Maya (Delusion/Deceitfulness)

These emotional states create the conditions for karmic influx and bondage

Liberation Path:

Complete exhaustion of all accumulated karma

Once aghātiyā karmas (non-harming karmas) are exhausted, the soul attains Moksha

Once all karma is shed, the soul ascends to Siddha Loka (realm of perfected souls) at the cosmic apex

The liberated soul experiences its true, infinite nature: infinite faith, infinite knowledge, infinite power, and infinite bliss (ananta-chalāna)

6. ETHICAL CODE: THE FIVE GREAT VOWS (PANCHA MAHĀVRATAS)

Mahavira established the Five Great Vows as the cornerstone of monastic ethics. These represent the highest standard of spiritual conduct for ascetics seeking liberation.

The Five Great Vows (Mahāvratas)

Ahimsa (Non-Violence)

Most fundamental and emphasized vow in Jainism

Absolute prohibition against causing harm, injury, or violence to any living being

Extends to humans, animals, insects, plants, and microorganisms

Includes harm through thought, speech, and action

For monks: requires extreme care not to injure even microscopic organisms

Represents the highest ethical principle and cornerstone of Jain philosophy

Satya (Truthfulness)

Complete abstention from lying and falsehood

Speaking truth at all times, irrespective of consequences

Also requires avoiding speech that causes harm, even if technically true

Includes honesty in thought and intention

Asteya (Non-Stealing)

Complete prohibition against taking anything not freely given

Applies to material objects, ideas, time, and energy

Requires respect for others’ property and rights

Brahmacharya (Celibacy/Chastity)

Complete abstention from sexual relations and sexual thoughts

For monks and nuns: vow of total celibacy

Represents complete renunciation of sensual desires

Differentiates Mahavira’s teachings from Parshvanatha’s four vows (Brahmacharya was Mahavira’s addition)

Aparigraha (Non-Attachment/Non-Possession)

Complete renunciation of personal possessions

Includes non-attachment to people, relationships, and emotions

Represents detachment from all worldly concerns

Monks maintain only bare necessities: robes, eating bowl, and spiritual texts (for some traditions)

Application: Mahāvratas vs. Anuvratas

For Monastic Orders (Mahāvratas – Great Vows):

Strict, uncompromising observance

Complete renunciation of worldly life

Central to the ascetic path to liberation

For Laypeople (Anuvratas – Lesser Vows):

Modified, practical versions of the great vows

Adapted to household and occupational responsibilities

Still binding but with flexibility:

Ahimsa: Minimize harm; avoid professions causing violence

Satya: Truthfulness in dealings without causing harm

Asteya: Honest commerce; no theft

Brahmacharya: Chastity and loyalty to spouse

Aparigraha: Limit possessions; avoid excessive accumulation

Significance: This dual system allowed Jainism to maintain rigorous spiritual standards while remaining accessible to ordinary people.

7. THEORY OF KNOWLEDGE (JÑĀNA PRAMĀṆA)

Mahavira presented a sophisticated epistemology (theory of knowledge) recognizing multiple valid means and types of knowledge:

Five Types of Knowledge (Jñāna)

Mati-Jñāna (Sensory/Perceptual Knowledge)

Knowledge obtained through the five senses

Subject to error and limitation

Dependent on sense organs and mental interpretation

Examples: seeing, hearing, tasting, touching

Śruta-Jñāna (Scriptural Knowledge)

Knowledge acquired through learning from scriptures and teachings

Understanding obtained by interpreting words, writings, and gestures

Dependent on language and symbolic representation

Transmitted through sacred texts and teachings of Tīrthaṅkaras

Āvadhi-Jñāna (Clairvoyance)

Transcendental or supernatural knowledge

Direct perception of material objects beyond ordinary sensory range

Knowledge of objects in different locations without sensory mediation

Possessed by higher beings and advanced ascetics

Manahparyaya-Jñāna (Telepathic/Mind-Based Knowledge)

Knowledge of others’ thoughts and mental states

Direct perception of the minds of other beings

Understanding of intentions and thoughts without communication

Rare ability possessed by highly advanced ascetics

Kevala-Jñāna (Omniscience)

Perfect, absolute knowledge of all things in all aspects

Complete and unrestricted perception of reality

Knowledge possessed only by enlightened beings (Kevalins/Jinas)

Cannot be fully expressed in language due to its transcendent nature

Achieved upon complete removal of knowledge-obscuring karma

Means of Knowledge (Pramāṇa)

Perception: Direct, immediate experience through senses or higher faculties

Inference: Logical deduction from perceived evidence

Scriptural Testimony: Authority of Jain sacred texts and Tīrthaṅkara teachings

Analogy: Drawing conclusions based on similarities

Theory of Viewpoints (Nayavāda)

Concept: Recognizes that all ordinary knowledge is necessarily partial, being always relative to some particular point of view

Implication: Different perspectives or viewpoints (nayas) can validly apprehend different aspects of reality

Application: Encourages intellectual humility—acknowledgment that no single viewpoint captures complete truth

Philosophical Significance: Supports pluralism and acceptance of diverse perspectives

8. PHILOSOPHICAL DOCTRINES: ANEKĀNTAVĀDA AND SYĀDVĀDA

These doctrines represent one of Jainism’s most significant contributions to Indian philosophy, promoting pluralism, tolerance, and intellectual relativism:

Anekāntavāda (Non-Absolutism/Doctrine of Manifoldness)

Definition: Reality is complex and multifaceted, possessing infinite modes of existence and qualities that cannot be completely grasped from any single viewpoint.

Core Principles:

Objects have infinite aspects and manifestations

No single viewpoint can capture the complete truth about any object or reality

Finite human perception, being limited, can only grasp partial aspects

Only Kevalins (omniscient beings) can comprehend objects in all their aspects and manifestations

All other beings are necessarily limited to partial knowledge

Philosophical Implications:

Rejection of Absolutism: Explicitly rejects dogmatic claims of exclusive truth

Promotion of Pluralism: Acknowledges validity of multiple perspectives

Intellectual Tolerance: Encourages acceptance of different viewpoints and philosophical schools

Humility: Cultivates recognition of limitations in human knowledge and understanding

Example: An elephant can be understood as:

From a zoological perspective: a large mammal

From an economic perspective: a source of labor

From a religious perspective: a sacred animal

From an environmental perspective: a keystone species

All these are partial but valid perspectives; no single view exhausts the complete reality of “elephant-ness”

Syādvāda (Doctrine of Conditional Predication)

Definition: Also called the “Seven-Fold Predication,” syādvāda systematizes the principle that statements about reality should be qualified with “syāt” (perhaps/maybe/conditionally), acknowledging that truth is dependent on perspective and context.

Seven-Fold Formula:

Syāt asti (Perhaps it is)—Affirmative assertion from one perspective

Syāt nāsti (Perhaps it is not)—Negative assertion from another perspective

Syāt asti nāsti (Perhaps it both is and is not)—From different perspectives simultaneously

Syāt asti anirvachānīya (Perhaps it is indescribable)—Beyond dual description

Syāt nāsti anirvachānīya (Perhaps it is not and is indescribable)

Syāt asti nāsti anirvachānīya (Perhaps it is and is not and is indescribable)

Syāt anirvachānīya (Perhaps it is entirely indescribable)

Philosophical Significance:

Epistemological Modesty: Recognizes that all knowledge statements are provisional and conditional

Linguistic Precision: Qualifies assertions with “maybe” to indicate dependence on viewpoint

Logical Consistency: Allows apparently contradictory statements to coexist without contradiction

Skepticism: Mitigates rigid dogmatism in philosophical discourse

Relationship to Anekāntavāda: If reality is multifaceted (anekāntavāda), then any statement about it must be qualified by perspective (syādvāda); the two doctrines are complementary.

Modern Philosophical Relevance

These doctrines have been recognized as precursors to modern relativism and perspectivism:

Analogies in Western Philosophy: Similar to Nietzsche’s perspectivism and postmodern epistemology

Contemporary Pluralism: Supports multicultural and multi-ideological societies requiring tolerance and recognition of diverse viewpoints

Scientific Application: Reflects modern scientific understanding that observation depends on perspective (relativity in physics; paradigm-dependent science)

Interfaith Dialogue: Provides philosophical foundation for respectful engagement with different religious and philosophical traditions

9. JAIN COUNCILS AND SCRIPTURAL DEVELOPMENT

First Jain Council (c. 300 BCE)

Location: Pataliputra (modern Patna)

Presiding Authority: Sthulbhadra (Mahavira’s chief disciple)

Purpose: Codification and preservation of Mahavira’s teachings following the eventual disappearance of monks with direct oral knowledge

Outcome:

Compilation of canonical texts called “Angas” (Limbs) — 12 foundational scriptures

Establishment of authoritative doctrinal framework

Preservation of Jain philosophy before textual knowledge could be lost

Creation of standardized teachings to prevent doctrinal drift

Significance: Ensured institutional continuity of Jain philosophy and ethics

Second Jain Council (c. 512 CE)

Location: Vallabhi (in present-day Gujarat)

Leading Scholar: Devardhigani Kshemasramana

Purpose: Further codification and supplementation of canonical literature

Outcomes:

Addition of “Upangas” (Sub-limbs) — supplementary texts expanding on the Angas

Additional philosophical elaboration and commentary

Documentation of sectarian differences that had emerged

Significance: Reflected evolution of Jain thought and sectarian development over nearly 800 years

Canonical Texts

Angas (12 primary scriptures):

Contain core teachings on metaphysics, ethics, and spiritual practice

Oldest and most authoritative texts in Jainism

Upangas and Other Texts:

Supplementary and interpretive literature

Include philosophical treatises and practical guidance

Important Texts:

Acharanga Sutra: Oldest Jain scripture, containing accounts of Mahavira’s ascetic practices

Bhagavati Sutra: Contains detailed teachings on karma and metaphysics

Tattvartha Sutra: Systematic philosophical exposition, accepted by both major sects as authoritative

10. SECTS OF JAINISM

Following Mahavira’s death, Jainism developed internal divisions leading to two major sects with distinct practices and beliefs:

Origins of the Sectarian Split

Traditional Account (Digambara Perspective):

Magadha Famine: A severe famine in Magadha forced migration of monks

Migration: Acharya Bhadrabahu led a group of monks southward to escape the famine, accompanied by Chandragupta Maurya (founder of Mauryan Empire)

Divergence: Monks remaining in North India (led by Sthulabhadra), faced harsh conditions, gradually adopted white robes as a concession

Return and Conflict: When southern monks returned after the famine, they found northern monks had adopted clothing, leading to permanent division

Modern Scholarly Perspective:

Textual evidence (art, philosophy, scripture codification) suggests the definitive formation of sectarian differences occurred in the 3rd-6th century CE

Gradual doctrinal differences accumulated over centuries before formal schism

Both traditions developed canonical texts and philosophical positions independently

The Two Major Sects

1. ŚVETĀMBARA (“White-Clad”)

Geographical Distribution: Predominantly North and Western India (Gujarat, Rajasthan, Maharashtra)

Monastic Practice:

Monks wear white robes (suits) as signs of renunciation

Practical accommodation reflecting moderate interpretation of asceticism

Nuns also permitted and actively engaged in religious life

Scriptural Authority:

Believe that original Jain scriptures (11 Angas and 14 Purvas) are preserved in their tradition

Canonical texts compiled at Vallabhi Council (512 CE)

Acknowledge incompleteness but maintain textual authority

Doctrine of Women:

Most Significant Difference: Women can become Tīrthaṅkaras

Female Tīrthaṅkaras: Accept Malli (19th Tīrthaṅkara) as female (whose name means “Mill”)

Women capable of moksha in the current lifetime

Practice of Sabastra Guru (acceptance of female teachers)

Active participation of nuns (Sadhvis) in monastic orders

Views on Marriage and Renunciation:

Believe Mahavira married and that 23rd Tīrthaṅkara Parshvanatha was married

Accept that renunciation does not require complete denial of past family status

Vow System:

Follow teachings of Parshvanatha (four vows without brahmacharya as foundational)

Mahavira’s five vows are practiced but interpreted more flexibly

Ritual Practice:

Engage in idol worship (murtipuja) in temples

Statues adorned with jewels, clothed, and depicted with elaborate detail and glass eyes

Regular worship rituals and ceremonial worship

Perform arati (waving of lights) over idols

Sub-sects:

Murtipujaka: Traditional idol-worshipping Śvetāmbaras

Sthanakvasi: Reject idol worship; use prayer halls instead of temples (emerged 17th century)

Terapanthi: Reformed movement emphasizing asceticism and minimal ritualism

Taranapanthi: Emphasize sacred texts over idols; against caste distinctions

2. DIGAMBARA (“Sky-Clad/Naked”)

Geographical Distribution: Predominantly South and Central India (Karnataka, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra)

Monastic Practice:

Monks practice complete nudity as essential to renunciation

Renunciation must include freedom from all possessions, including clothing

Symbolizes total renunciation of material concerns

Nuns wear simple white unstiched sarees (called Aryikas), not permitted full nakedness

Scriptural Authority:

Believe original canonical texts were lost in antiquity

Foundational scripture: Shatkhandagama (based on oral transmission from monk Dharasena, 1st-2nd century CE)

Preserved through masters Puşpadanta and Bhūtabali

Accept Tattvartha Sutra as authoritative philosophical text (shared with Śvetāmbaras)

Doctrine of Women:

Most Contentious Difference: Women cannot become Tīrthaṅkaras

Believe women lack the “adamantine body” (hard, incorruptible body) necessary for omniscience

Claim women cannot achieve liberation in current lifetime

Must be reborn as men to attain moksha

Historical justification: Claim the 19th Tīrthaṅkara Malli was actually a man (not female as Śvetāmbaras claim)

Restriction on female participation in highest spiritual ranks

Theological Justification for Gender Exclusion:

Women perceived as intrinsically harmful (historical rationale related to menstruation and its microscopic consequences—now rejected by modern Jain thought)

Practical argument: Full nudity required for liberation impossible for women in society

Doctrinal: Women lack qualities necessary for kevalajnana

Vows and Practice:

Strictly follow Pancha Mahāvratas (five great vows) of Mahavira

More rigid interpretation of monastic rules

Brahmacharya considered essential

More austere lifestyle

Ritual Practice:

Also practice idol worship but with distinct iconography

Statues depicted as nude, unadorned, without jewels

Plain, contemplative representations

Some Digambara sub-sects reject idol worship entirely

Namokar Mantra:

Recite only first five lines of the Namokar prayer (unlike Śvetāmbaras who recite all nine lines)

Sub-sects:

Bisapantha: Original form of Digambara sect; widespread in South India

Terapanthi-Digambara: Reformed Digambara movement

Sthanakvasi-Digambara: Some Digambara groups reject idol worship

Other Doctrinal Differences

| Aspect | Śvetāmbara | Digambara |

|---|---|---|

| Mahavira’s Conception | Transferred from Brahmin womb to Kshatriya womb by Indra | Single conception; no embryo transfer |

| Mahavira’s Omniscience Condition | Experienced illness during kevalajnana | Never suffered illness |

| Scriptural Preservation | Original scriptures preserved | Original texts lost; reconstructed traditions |

| Liberation Timeline | Immediate upon achieving kevalajnana | Possible delay based on karma |

Significance of Sectarian Division

The sectarian diversity within Jainism reflects:

Adaptation to Regional Contexts: Different societies required different practices

Philosophical Flexibility: Core ethics remained constant; practices evolved

Theological Debate: Earnest disagreement on metaphysical matters despite shared core values

Living Tradition: Jainism maintained internal diversity while preserving fundamental unity on non-violence and spiritual seeking

11. SPREAD AND CULTURAL IMPACT OF JAINISM

Mechanisms of Spread

Ascetic Wandering:

Jain monks and nuns (sādhus and sādhvis) traveled extensively

Spread teachings through wandering, preaching, and personal example

Engaged in public debates with rival sects and persuasion

Established communities wherever they settled

Royal Patronage:

Mauryan emperors (particularly post-Ashoka period) supported Jain establishments

Kingdom of Magadha became center of Jain learning

Wealthy merchants and landowners funded temple construction and monastic establishments

Royal support facilitated institutional development

Cultural Influence:

Jain merchants established networks across India

Trade connections facilitated ideological spread

Cultural practices and ethical teaching influenced urban centers

Socio-Economic Impact

Trade and Commerce:

Jain ethical principles (ahimsa, satya, asteya) naturally aligned with honest commerce

Historically, application of non-violence drove Jain community toward trade and banking

Jains became dominant merchants and businesspeople in many regions

Established financial institutions and mercantile guilds

Reputation for ethical business practices and reliability

Social Influence:

Promotion of vegetarianism and animal welfare

Emphasis on education and literacy

Philanthropic contributions to social welfare

Urban concentration leading to cultural sophistication

Demographic Profile:

Despite constituting only 0.37% of India’s population (4.45 million as per 2011 Census)

Jains represent disproportionate wealth and influence

Among India’s most educated and affluent communities

Concentrated in urban areas and specific regions (Maharashtra 31.46%, Rajasthan 13.97%, Gujarat 13.02%, Madhya Pradesh 12.74%)

Jain Contributions to Art and Architecture

Mauryan and Post-Mauryan Periods:

Rock-cut caves and monastic establishments

Yaksha and Yakshi sculptures (shared with Buddhism and Hinduism)

Medieval Period (10th-13th centuries) — Peak of Jain temple construction:

Dilwara Temples (Mount Abu, Rajasthan): Masterpieces of marble carving with intricate designs

Ranakpur Temple (Rajasthan): Distinctive Jain architectural style

Sponsored by wealthy merchants and supported by Solanki and Chalukya dynasties

Demonstrated fusion of devotion and artistic excellence

Influenced broader Indian architectural traditions

Artistic Features:

Elaborate stone and marble carving

Intricate sculptural details

Multiple temple spires (shikhara) arranged in clusters

Open courtyards and mandapas (pavilions)

Extensive use of precious materials reflecting devotional commitment

IMPORTANT CONCEPTS & TERMS FOR UPSC

Core Philosophical Terms

Tīrthaṅkara: “Ford-maker” or “Path-breaker”; spiritual teacher who discovers and reveals the path (ford) across the ocean of worldly existence (samsāra); helps others cross from bondage to liberation

Kevala-Jnana / Kaivalya: Omniscience; perfect and absolute knowledge achieved upon complete removal of knowledge-obscuring karma; state of infinite knowledge possessed by enlightened beings

Moksha / Moksa: Liberation; ultimate goal of Jainism; complete freedom from the cycle of birth, death, and rebirth; state of infinite bliss and perfection

Jīva: Soul; sentient, conscious principle; possesses inherent qualities of knowledge, perception, power, and bliss

Ajīva: Non-soul; matter; insentient, non-conscious principle including physical matter and karmic particles

Samsāra: Cycle of birth, death, and rebirth; worldly existence characterized by suffering and bondage

Ethical and Practical Terms

Ratnatraya: Three Jewels—Right Belief, Right Knowledge, Right Conduct; integrated framework for spiritual development

Mahāvratas: Five Great Vows (Ahimsa, Satya, Asteya, Brahmacharya, Aparigraha); binding ethical principles for ascetics

Anuvratas: Lesser Vows; modified versions of Great Vows adapted for laypeople

Ahimsa: Non-violence; core principle of Jainism emphasizing abstention from harm to all living beings

Aparigraha: Non-attachment or non-possession; renunciation of material possessions and emotional attachments

Satya: Truthfulness; speaking and thinking truth at all times

Asteya: Non-stealing; respecting others’ property and rights

Brahmacharya: Celibacy; abstention from sexual relations

Philosophical Doctrines

Anekāntavāda: Non-absolutism or doctrine of manifoldness; reality is multifaceted with infinite aspects not fully graspable from single perspective

Syādvāda: Conditional predication; statements qualified with “perhaps” (syāt) acknowledging perspective-dependence of truth

Nayavāda: Theory of partial standpoints; recognition that all knowledge is necessarily partial and relative to viewpoint; basis for intellectual tolerance

Karmic Framework

Āsrava: Influx of karmic matter toward soul due to passions and improper actions

Bandha: Bondage; binding of karmic particles to soul

Samvara: Stoppage; prevention of new karmic influx through ethical conduct

Nirjara: Exhaustion or wearing away of karma through austerities and spiritual discipline

Ghātiyā Karmas: Harming karmas; directly obscure soul’s powers (perception-obscuring, knowledge-obscuring, deluding, obstacle-creating)

Aghātiyā Karmas: Non-harming karmas; determine physical circumstances and lifespan (body, lineage, lifespan, feeling-producing)

Sectarian Terms

Śvetāmbara: White-clad; sect allowing monastic garments; permits female participation in spiritual roles

Digambara: Sky-clad; sect practicing monastic nudity; restricts women’s access to highest spiritual attainments

Murtipuja: Idol worship; ritual worship of Tīrthaṅkara statues in temples

Sthanakas: Prayer halls used by non-idol-worshipping Jain sects

Read More: Ancient India Notes

Discover more from Simplified UPSC

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.