The Vedic Age: A Comprehensive Study

Contents

The Vedic Age:

Introduction: Understanding the Vedas and Vedic Period

The Vedic Age (c. 1500–600 BCE) was an era in ancient India marked by the composition of the Vedas and saw the transition from tribal, pastoral societies to settled agrarian communities. The social structure evolved from a relatively egalitarian system to one governed by the varna hierarchy, which laid the foundation for later caste divisions. Political organization shifted from elected tribal chiefs and assemblies to hereditary monarchies, and religious life centered on rituals, sacrifices, and reverence for natural forces. The wisdom and practices of this era deeply influenced Indian civilization’s social, philosophical, and cultural traditions.

Meaning of Vedas:

The word “Veda” is derived from the Sanskrit root “Vid”, which means “to know” or “knowledge”. The Vedas represent sacred spiritual knowledge, considered the best of all knowledge in Hindu tradition. These ancient texts are:

Apauruṣeya (not of human origin, superhuman, authorless)

Śruti (what is heard), distinguishing them from Smṛti (what is remembered)

Nitya (eternal), believed to have existed since the beginning of time

Divine revelations of sacred sounds and texts heard by ancient sages (rishis) during intense meditation

The Vedas constitute a large body of religious texts composed in Vedic Sanskrit, representing the oldest layer of Sanskrit literature and the oldest scriptures of Hinduism. They are essentially a compilation of hymns, prayers, charms, litanies, sacrificial formulas, ritual instructions, and philosophical wisdom.

The Vedic Period and Its Classification

The Vedic Age or Vedic Period (c. 1500-500 BCE) represents a pivotal epoch in Indian history when Vedic literature was composed in the northern Indian subcontinent. This period occurred between the end of the urban Indus Valley Civilisation and a second urbanization in the central Indo-Gangetic Plain around 600 BCE.

The Vedic period is conventionally divided into two distinct phases:

Early Vedic Period (1500-1000 BCE)

Also called the Rig Vedic Period

Characterized by semi-nomadic, pastoral lifestyle

Society organized around tribes (jana)

Composition of the Rigveda

Settlement primarily in the Sapta Sindhu (Seven Rivers) region of northwestern India

Later Vedic Period (1000-500/600 BCE)

Marked by transition to settled agricultural communities

Expansion eastward into the Gangetic plains

Composition of Yajurveda, Samaveda, Atharvaveda, and associated texts

Emergence of larger kingdoms and more complex political structures

Development of the varna system

Q. 1 Underline the changes in the field of society and economy from the Rig Vedic to the later Vedic period. (10 M) {UPSC Mains 2024 GS1 }

The Four Vedas and Their Prominent Content

The canonical division of the Vedas recognizes four primary texts:

1. Rigveda (Ṛgveda)

Overview:

The oldest and most important of the four Vedas

Composed approximately between 1500-1200 BCE

Contains 1,028 hymns (suktas) comprising about 10,600 verses (ṛc)

Organized into 10 books called Mandalas

Structure and Content:

The Rigveda’s hymns are arranged in collections, each dealing with particular deities:

Mandala 1 (191 hymns): Primarily dedicated to Agni, Indra, and Varuna, including philosophical hymns

Mandala 2-7 (Family Books): These are the oldest sections, composed by specific priestly families:

Uniform format with hymns arranged by deity

Predominantly discuss cosmology, rituals, and praise of gods

Mandala 3 (62 hymns): Contains the famous Gayatri Mantra (verse 3.62.10), attributed to Viśvāmitra

Mandala 8 (103 hymns): Attributed to the Kaṇva family

Mandala 9: Entirely dedicated to Soma, the sacred ritual drink

Mandala 10 (191 hymns): Includes later philosophical hymns, the Purusha Sukta (describing the cosmic sacrifice and origin of varnas), and the Nadistuti (praise of rivers)

Principal Deities:

Indra (god of rain and thunder): Most frequently mentioned, praised for slaying the demon Vritra

Agni (fire god): First word of the Rigveda; sacrificial fire deity

Varuna (cosmic order): Guardian of ṛta (cosmic law)

Soma: The sacred plant and its juice used in rituals

Others: Mitra, Ushas (dawn), Surya (sun), Rudra, Maruts, Asvins

Themes:

Hymns of praise to natural forces and Vedic deities

Cosmological speculation about the origin of the universe

Questions about existence and divine nature

Prayers for prosperity, victory, and well-being

2. Yajurveda

Overview:

Known as the “Veda of Ritual” or “Veda of Sacrifices”

Derived from “Yajus” (sacrificial formula) and “Veda” (knowledge)

Primarily a prose manual for performing Vedic rituals and sacrifices

Contains liturgical texts and mantras used by priests during ceremonies

Divisions:

White Yajurveda (Vajasaneyi Samhita): Contains formulas without detailed explanations

Black Yajurveda (Taittiriya Samhita): Includes formulas mixed with explanatory prose

Content and Structure:

The White Yajurveda’s Vajasaneyi Samhita has 40 chapters (adhyayas) covering:

Chapters 1-2: Darśapūrṇamāsa (Full and new moon rituals)

Chapter 3: Agnihotra (daily milk oblation) and Cāturmāsya (seasonal sacrifices)

Chapters 4-8: Soma sacrifice rituals

Chapters 9-10: Vājapeya (chariot race) and Rājasūya (royal consecration)

Chapters 11-18: Agnicayana (fire altar construction – 360 days)

Chapters 22-25: Aśvamedha (horse sacrifice – conducted by kings)

Chapters 30-31: Puruṣamedha (symbolic sacrifice of cosmic man)

Chapter 35: Pitriyajna (funeral and ancestral rites)

Chapter 40: Isha Upanishad – philosophical treatise on the Self (Atman)

Significance:

Serves as a practical guide for priests (adhvaryu) conducting sacrifices

Contains detailed instructions on altar construction, offerings, and ritual chants

Explains proper performance of ceremonies with precise mantras and procedures

3. Samaveda

Overview:

The “Veda of Melodies” or “Veda of Chants”

Primarily consists of musical arrangements of verses taken from the Rigveda

Used specifically for singing during religious rituals and soma sacrifices

Content:

Most verses are adapted from Rigveda but arranged for melodic chanting

Focuses on the musical aspect of rituals

Used by the udgātṛ priests who sang during ceremonies

Considered the origin of Indian classical music tradition

Significance:

Demonstrates the importance of sound and music in Vedic rituals

Represents the aesthetic dimension of Vedic religion

Preserves ancient melodic traditions

4. Atharvaveda

Overview:

The “Veda of Magical Formulas” (though scholars debate this epithet)

Represents the most practical and worldly of the four Vedas

Added later to the original three Vedas (trayī vidyā – triple knowledge)

Contains hymns, spells, charms, and incantations for everyday concerns

Content Categories:

The Atharvaveda addresses diverse aspects of daily life:

Bhaiṣajyāni (Healing charms): Spells for curing diseases and ailments

Āyuṣyāni (Longevity prayers): Prayers for long life and health

Ābhicārikāni: Imprecations against demons, sorcerers, and enemies

Strīkarmāṇi: Charms related to women’s concerns

Sāmmanasyāni: Charms for harmony and domestic peace

Rājakarmāṇi: Charms for kingship and royalty

Pauṣṭikāni: Charms for prosperity and protection from danger

Dual Nature:

Śānta (auspicious/holy magic): Healing, protection, prosperity – associated with sage Atharvan

Ghora (harmful/black magic): Curses, exorcisms – associated with sage Angiras

Themes:

Medicinal herbs and healing practices

Protection from evil spirits and demons

Love charms and spells for attraction

Success in warfare, agriculture, and trade

Philosophical and speculative hymns (similar to Upanishads)

Significance:

Provides insight into popular religion and superstitions of ordinary people

Contains practical knowledge about everyday life

Bridges the gap between elite ritual practices and common concerns

Includes some profound philosophical material

Parts of the Vedas: A Four-Fold Division

Each Veda is divided into four major textual layers or subdivisions:

1. Samhitas (संहिता) – The Collections

Definition and Nature:

The term “Samhita” means “collection” or “compilation”

Represents the basic mantra text of each Veda

The oldest and most fundamental layer of Vedic literature

Contains the actual hymns, verses, prayers, and ritual formulas

Content:

Rigveda Samhita: 1,028 hymns in 10 Mandalas

Yajurveda Samhita: Prose mantras and sacrificial formulas

Samaveda Samhita: Melodic verses for chanting

Atharvaveda Samhita: Magical charms and spells

Purpose:

Used for recitation during rituals

Contain invocations to deities

Express philosophical and cosmological ideas

Preserve ancient wisdom and religious practices

Classification:

Form the Karma-Kanda (section on action/ritual) along with Brahmanas

2. Brahmanas (ब्राह्मण) – The Ritual Commentaries

Definition and Nature:

The term “Brahmana” refers to prose texts that explain and elaborate on the Samhitas

Dated approximately to 900-700 BCE

Provide detailed commentaries on rituals, ceremonies, and sacrifices

Content and Purpose:

The Brahmanas serve multiple functions:

Ritual Explanation: Detailed procedures for performing Vedic sacrifices (yajnas)

Symbolic Interpretation: Explain the meaning and symbolism of ritual acts

Mythological Context: Incorporate myths and legends to justify rituals

Scientific Knowledge: Include observational astronomy and geometry (especially for altar construction)

Theological Discussion: Explore the relationship between ritual action and cosmic order

Major Brahmanas:

Aitareya Brahmana (attached to Rigveda): Explains soma sacrifice and royal ceremonies

Shatapatha Brahmana (attached to Yajurveda): The largest and most complete Brahmana; contains extensive ritual explanations and philosophical discussions

Tandya/Panchavimsha Brahmana (attached to Samaveda)

Gopatha Brahmana (attached to Atharvaveda)

Ritual Structure Described:

Brahmanas detail the tripartite ritual structure:

Pūrva-karma (preliminaries): Preparation, purification, establishing sacred fire

Pradhāna-karma (main sacrifice): Core offerings and recitations

Uttara-karma (concluding rites): Final offerings and dismissal

Significance:

Transform simple offerings into elaborate ceremonies

Reconceptualize sacrifice as cosmic drama

Establish priestly specialization and expertise

Form the Karma-Kanda along with Samhitas

3. Aranyakas (आरण्यक) – The Forest Books

Definition and Nature:

The term “Aranyaka” derives from “aranya” meaning “forest”

Called “Forest Books” or “Forest Treatises”

Composed around 700-500 BCE

Transitional texts bridging ritual Brahmanas and philosophical Upanishads

Why “Forest Books”?

The name reflects their context and purpose:

Originally studied by hermits (vanaprasthas) living in forest retreats

Meant for those who had retired from household life for spiritual contemplation

Considered too sacred or esoteric for village study

Required meditative environment away from worldly distractions

Content and Themes:

Aranyakas represent a shift in focus:

From External to Internal: Move away from physical rituals toward mental and symbolic sacrifices

Mystical Interpretations: Provide symbolic meanings of yajnas and ritual elements

Meditation Techniques: Teach methods based on symbolical interpretations of sacrificial rites

Philosophical Speculation: Begin exploring abstract concepts like Atman and Brahman

Connection to Nature: Emphasize the forest as a liminal space for spiritual transformation

Example:

The Brihadaranyaka Upanishad begins with a mental performance of the Ashvamedha (horse sacrifice), demonstrating this internalization of ritual

Purpose:

Bridge the “Way of Work” (Karma Marg) of the Brahmanas with the “Way of Knowledge” (Jnana Marg) of the Upanishads

Facilitate transition from external ritual to internal contemplation

Prepare seekers for deeper philosophical inquiry

Classification:

Mark the beginning of Jnana-Kanda (section on knowledge)

Appropriate for Vanaprastha (forest-dwelling) stage of life

4. Upanishads (उपनिषद्) – The Philosophical Texts

Definition and Nature:

The term “Upanishad” means “sitting down near” (a teacher)

Also called “Vedanta” meaning “end of the Veda” in both senses: conclusion and culmination

Composed from around 800 BCE onward

Represent the philosophical and metaphysical core of Vedic thought

Principal (Oldest) Upanishads:

Brihadaranyaka Upanishad

Chandogya Upanishad

Katha Upanishad

Kena Upanishad

Aitareya Upanishad

Taittiriya Upanishad

Mundaka Upanishad (source of India’s motto: Satyameva Jayate)

Mandukya Upanishad

Prasna Upanishad

Others (over 200 Upanishads exist, though 10-13 are considered principal)

Central Philosophical Concepts:

1. Brahman (ब्रह्मन्) – The Ultimate Reality

The absolute, unchanging, impersonal reality that pervades all existence

The cosmic principle underlying the universe

Both transcendent and immanent

Described as Sat-Chit-Ananda (Being-Consciousness-Bliss)

Beyond description, yet characterized as infinite and eternal

2. Atman (आत्मन्) – The Individual Soul

The true self or individual soul within all beings

Eternal, unchanging, pure consciousness

Distinct from the body, mind, and ego (ahamkara)

The animating essence that gives life to all creatures

Compared to Prana (breath) that holds the body together

3. The Unity of Atman and Brahman

The revolutionary teaching: Atman IS Brahman

Expressed in the great saying “Tat Tvam Asi” (Thou art That)

Concept of Advaita (non-duality): individual soul and universal reality are ultimately identical

Realization of this unity is the goal of spiritual practice

4. Maya (माया) – Cosmic Illusion

The illusory nature of the phenomenal world

Veils the true reality of Brahman

Causes ignorance (Avidya) and identification with body and mind

Must be transcended to realize truth

5. Karma (कर्म) – Action and Consequence

The universal law of cause and effect

Every action produces consequences that bind the soul

Determines future births and circumstances

6. Samsara (संसार) – The Cycle of Rebirth

The continuous cycle of birth, death, and rebirth

Fueled by karma and attachment

Characterized by suffering (dukkha)

Seen as bondage from which liberation is sought

7. Moksha (मोक्ष) – Liberation

The ultimate goal of human existence

Liberation from the cycle of samsara

Achieved through self-realization (Atma-jnana): direct knowledge of one’s true nature as Atman

Attained through meditation, self-inquiry, ethical living, and grace

State of eternal freedom and union with Brahman

Means to Liberation:

Meditation (dhyana): Contemplation on the Self

Self-inquiry (atma-vichara): Investigation into “Who am I?”

Knowledge (jnana): Understanding the true nature of reality

Ethical living (dharma): Following righteous conduct

Renunciation (vairagya): Detachment from worldly desires

Significance:

Shift from external ritual to internal spiritual realization

Foundation of Hindu philosophical schools, especially Vedanta

Influenced Buddhism, Jainism, and other Indian philosophies

Represent the Jnana-Kanda (section on knowledge)

Appropriate for Sannyasa (renunciant) stage of life

Key Teaching Style:

Often presented as dialogues between teacher and student

Use of stories, parables, and metaphors

Question-and-answer format exploring deep existential issues

History of Vedic People (Aryans): Migration and Theories

The Aryan Identity

The term “Arya” or “Aryan” appears in Vedic texts, particularly the Rigveda, where the composers describe themselves as Arya. This term is best understood as a cultural and linguistic identity rather than a racial one. It signifies “noble,” “civilized,” or “refined” people.

Theories of Aryan Origins

The question of Aryan origins has been one of the most debated topics in Indian history, with several competing theories:

1. Aryan Migration Theory (Most Widely Accepted)

Proponents and Evidence:

The Aryan Migration Theory suggests that:

Indo-European speaking peoples (called Aryans) migrated from the Central Asian steppes into the Indian subcontinent

Migration occurred around 1500 BCE from regions including southern Russia, Central Asia, and the Eurasian steppes

This was a gradual process of migration and settlement, NOT a sudden invasion

The migration brought Indo-Aryan languages (ancestral to Sanskrit) to the subcontinent

Supporting Evidence:

Linguistic Evidence:

Sanskrit belongs to the Indo-European language family

Shares common roots with Persian, Greek, Latin, and other European languages

This linguistic relationship requires explanation through historical contact

Archaeological Evidence:

Arrival of new cultural elements around 1500 BCE

Introduction of horse-drawn chariots

Ochre Coloured Pottery (OCP) culture possibly associated with early Aryans

Changes in settlement patterns in northwestern India

Genetic Evidence:

Recent genomic studies suggest mixture of populations

ANI (Ancestral North Indian) component shows Steppe ancestry

Mixing occurred between 4,200-1,900 years ago (2200 BCE – 100 CE)

Steppe ancestry disproportionately present in upper castes, particularly Brahmins

Ecological Evidence:

Widespread aridization in the second millennium BCE led to migrations

Water shortages and ecological changes in Eurasian steppes and India

Caused collapse of sedentary urban cultures and triggered large-scale movements

Textual Evidence:

The Baudhāyana Śrauta Sūtra (18.44:397.9) mentions: “Ayu went eastwards. His (people) are the Kuru Panchala and the Kasi-Videha. This is the Ayava (migration). (His other people) stayed at home. His people are the Gandhari, Parsu and Aratta.”

This suggests memory of an eastward migration from northwestern regions

Nature of Migration:

Likely occurred in waves or stages, not as a single event

Involved both peaceful settlement and conflict with existing populations

Led to gradual cultural synthesis between migrants and indigenous peoples

2. Aryan Invasion Theory (Largely Discredited)

Historical Context:

Proposed by colonial scholars like Max Mueller and William Jones in the 19th century

Suggested that Aryans were a “superior race” who conquered India through military invasion

Portrayed as fair-skinned warriors who subjugated darker-skinned Dravidians

Why Discredited:

Lack of archaeological evidence for large-scale military conquest

Racially motivated interpretation serving colonial ideology

No evidence of sudden violent disruption around 1500 BCE

Modern scholars reject the racial aspects and invasion narrative

Note: Critics of migration theory often conflate it with invasion theory, presenting migration as “Aryan Invasion” to discredit it

3. Indigenous Aryan Theory (Out of India Theory)

Claims:

Aryans were indigenous to the Indian subcontinent

No migration from outside occurred

Aryans were the creators of both Harappan and Vedic civilizations

Indo-European languages originated in India and spread outward

Arguments:

Points to cultural continuity in the subcontinent

Questions dating of Rigveda (claims earlier composition)

Emphasizes indigenous development

Criticisms:

Lacks support from mainstream linguistic, archaeological, and genetic evidence

Does not explain the Indo-European language distribution globally

Contradicts genetic studies showing Steppe admixture

Current Status:

Not widely accepted in mainstream academic scholarship

Considered more as nationalist counter-narrative than scholarly theory

Contemporary Understanding

Modern scholarship recognizes that:

The question involves linguistic, archaeological, genetic, and textual evidence

Migration was likely gradual and complex, involving multiple waves

There was interaction and synthesis between migrants and indigenous populations, not just conflict or replacement

The focus should be on cultural and linguistic identity rather than race

The process involved both accommodation and conflict

Settlement in India: Archaeological Sites

Early Vedic Settlement Pattern

Primary Region: Sapta Sindhu (सप्त सिन्धु)

The early Aryans first settled in the “Sapta Sindhu” or “Land of Seven Rivers”, which comprised:

Sindhu (Indus)

Vitasta (Jhelum)

Asikni (Chenab)

Parushni (Ravi)

Vipash (Beas)

Shutudri (Sutlej)

Sarasvati (now dried)

Geographic Coverage:

Modern-day eastern Afghanistan

Punjab region (Pakistan and India)

Western Uttar Pradesh

Parts of Haryana

Archaeological Sites and Cultures

Early Vedic Period Sites

1. Ochre Coloured Pottery (OCP) Culture Sites (c. 2000-1500 BCE)

Characteristics:

Bronze Age culture of Indo-Gangetic Plain

Pottery has red slip with ochre color

Black painted designs

Also called “Copper Hoard Culture” due to copper artifacts

Possibly associated with early Vedic culture

Major Sites:

Gungeria (Madhya Pradesh): Copper weapons and tools

Sites in eastern Punjab, northeastern Rajasthan, western Uttar Pradesh

Saharanpur district sites (Uttar Pradesh)

Cultural Features:

Rural culture with evidence of cultivation (rice, barley, legumes)

Pastoralism: cattle, sheep, goats, pigs, horses, dogs

Wattle-and-daub houses

Copper and terracotta ornaments

Later Vedic Period Sites

2. Painted Grey Ware (PGW) Culture Sites (c. 1200-500 BCE)

Characteristics:

Iron Age culture of western Gangetic plain

Fine, grey pottery with painted geometric patterns in black

Associated with Later Vedic period and early state formation

Marks introduction and spread of iron technology

Village and town settlements with domesticated horses

Dating:

Period I: c. 1300-1000 BCE (appearance in Ghaggar valley and upper Ganga)

Period II: c. 1000-600 BCE (spread into western Ganga valley)

Period III: c. 600-300 BCE

Major Excavated Sites:

Hastinapur (Meerut district, Uttar Pradesh)

On right bank of old Ganga River bed

Excavated by B.B. Lal in 1950s

First site where complete chronological position of PGW was established

Shows continuous occupation through multiple periods

Evidence of rice cultivation

Associated with Mahabharata tradition

Ahichchhatra (Bareilly district, Uttar Pradesh)

First reported site to yield Painted Grey Ware (1944)

Capital of Northern Panchala Mahajanapada

Shows cultural sequence: OCP → PGW → NBPW → Early Historic period

Continuous occupation from Vedic period to Gupta period

Atranjikhera (Etah district, Uttar Pradesh)

Located on banks of Kali Nadi, tributary of Ganga

Clear cultural sequence: OCP → Black and Red Ware → PGW → NBPW

Dating: c. 1100-600 BCE for PGW phase

Key site showing transition from rural to urban society

Evidence of early state formation and agro-metallurgical economy

Jakhera (near Atranjikhera, Etah district)

Shows similar cultural sequence

Evidence of agricultural and iron-based economy

Lal Qila (Bulandshahr district, Uttar Pradesh)

Located about 3 km west of Atranjikhera

On upper stream of Kali Nadi

Other Important PGW Sites:

In Uttar Pradesh:

Kampilya (Farrukhabad district)

Mathura region sites: Chhata, Mathura-Sadar, Mant

Hathras district sites: Sasni to Hathras alignment

Hulas (Saharanpur district)

In Haryana:

Bhagwanpura (Kurukshetra district)

Kunal (Fatehabad district): Shows three successive phases – Early Harappan, Mature Harappan, and PGW culture

Banawali (Fatehabad district)

Ropar (on border with Punjab)

In Delhi:

Purana Qila (Old Fort): Excavations revealed cultural layers from Medieval to Mauryan periods, with search for PGW evidence

In Rajasthan:

Bahaj village (Deeg district, Rajasthan): Recent ASI excavations (2024) revealed 4,500-year-old civilization with evidence of five periods including Vedic period. Over 15 yajna kunds found confirming Vedic rituals. Discovery of 23-meter-deep paleo-channel linked to mythical Saraswati River

Cultural Features of PGW Sites:

Iron tools and implements enabling agricultural expansion

Evidence of plough agriculture

Community hearths, storage bins, raised platforms

Fortifications at larger settlements (ditches, moats, embankments)

Transition from pastoral to agricultural economy

Development of craft specialization (pottery, metallurgy, textiles)

Settlement Density:

As of 2018, 1,576 PGW sites discovered

Most were small farming villages

“Several dozen” emerged as relatively large towns

High concentration in:

Upper Ganga-Yamuna doab region

Districts of Mathura, Bharatpur, Hathras

Later Vedic Expansion

Eastward Movement:

By the end of the Later Vedic period, Aryans expanded:

From Punjab and Sapta Sindhu region

Through the upper Gangetic basin

To Videha (North Bihar) in the north

To Koshala (eastern UP) in the east

Past the Vindhyas in the south

Important Kingdoms:

Kuru-Panchala: Initially dominant, centered around Hastinapur

Kosala: Eastern expansion

Kasi: Centered around Varanasi

Videha: Northern Bihar

Magadha: Eastern region (later became dominant)

Anga and Vanga: Eastern regions

Other Significant Archaeological Evidence

Harappan Sites in Haryana (Overlap Period):

Rakhigarhi (Hisar district, Haryana)

One of the largest Harappan sites (300-350 hectares)

Shows Early and Mature Harappan phases

Excavated by ASI and Deccan College

Evidence of planned township, drainage system, fire altars

4,600-year-old human skeletons found

Cemetery with mature Harappan period graves

Provides context for pre-Vedic culture in the region

Transition from Early to Later Vedic Period

The transformation from Early to Later Vedic period represents one of the most significant transitions in ancient Indian history, marked by fundamental changes in political, social, economic, and cultural spheres.

Political and Administrative Structure

Early Vedic Period (1500-1000 BCE)

Nature of Polity:

Tribal Organization:

Society organized into tribes called Jana (जन)

Essentially a tribal polity with kinship-based social relations

Semi-nomadic pastoral communities

Leadership Structure:

The Rajan (राजन्):

Tribal chief called Rajan or Raja

Known as “Janasya Gopa” (protector of the people)

Power was limited and checked by tribal assemblies

Often elected by the tribal council

Position becoming hereditary but not absolute

Primary responsibilities:

Leading tribe in wars and cattle raids

Protecting people and cattle

Settling disputes

Tribal Assemblies (Democratic Elements):

Sabha (सभा):

Smaller council of tribal elders

Advisory role to the Raja

Performed judicial functions

Samiti (समिति):

Larger assembly of tribe members

Involved in major decisions like war and peace

Women could participate

Vidatha (विदथ):

Another assembly mentioned in Rigveda

Women participated

Gana (गण):

Tribal gathering

Administrative Officials:

Purohita (पुरोहित): Priest with significant influence

Senani (सेनानी): Military commander

Limited bureaucratic structure

Key Characteristics:

Decentralized power structure

Raja as “primus inter pares” (first among equals)

Collective tribal decision-making

No standing army; warriors mobilized during conflicts

No formal administrative machinery

Later Vedic Period (1000-600 BCE)

Nature of Polity:

Territorial Kingdoms:

Shift from tribal Jana to territorial Janapada (जनपद)

Concept of Rashtra (territory) became more prominent than Jana (tribe)

Formation of monarchical states

Consolidation of power and centralization

Evolution of Kingship:

Enhanced Royal Authority:

Kingship became hereditary, passing from father to son

King viewed as divinely sanctioned

Raja assumed grander titles:

Virat (northern regions)

Samrat (eastern regions, supreme ruler)

Svarat (western regions, self-ruler)

Bhoja (southern regions, patron)

Royal Rituals to Legitimize Power:

Rajasuya (राजसूय): Royal coronation/consecration ceremony

Ashvamedha (अश्वमेध): Horse sacrifice – symbol of imperial power

Vajapeya (वाजपेय): Chariot race ritual for rejuvenation

Functions of the King:

Maintenance of law and order (Dharma)

Protection of people and territory

Collection of taxes (Bali and Bhaga)

Leading wars and conquests

Conducting religious sacrifices

Controller of social order

Administrative Development:

Specialized Officials:

Senani (सेनानी): Commander-in-Chief, head of army

Purohita (पुरोहित): Chief priest, continued importance

Sangrahitri (संग्रहीतृ): Treasurer/Collector managing royal income and taxes

Mahishi (महिषी): Chief Queen, ceremonial role in rituals

Gramini (ग्रामिणी): Village Head, responsible for local governance and tax collection

Adhyakshas (अध्यक्ष): Various superintendents

Revenue System:

Systematic taxation on agriculture

Bali (बलि): Voluntary gifts becoming expected tributes

Bhaga (भाग): Regular tax share

Gifts from subjects

Tributes from conquered tribes

War booty

Decline of Tribal Institutions:

Assemblies Lose Power:

Vidatha completely disappeared

Sabha and Samiti continued but character changed:

Dominated by princes and rich nobles

Lost democratic character

Women no longer permitted in Sabha

Village assemblies (Sabhas) took over local administration

Shift from kin-based authority to territorial administration

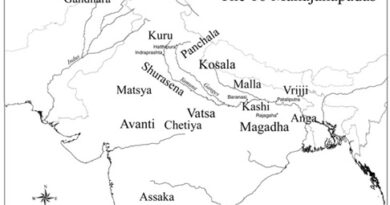

Emergence of Major Kingdoms:

Early Powerful Kingdoms:

Kuru Kingdom (Hastinapur region):

Modern Haryana and western Uttar Pradesh

Early political and cultural center

Ruled by Parikshit and Janamejaya

Panchala Kingdom:

East of Kurus

Known for intellectual advancement

King Pravahana Jaivali renowned for patronage of learning

Kosala and Videha:

Emerging in eastern Gangetic plains

Represented shift of power eastward

Kasi:

Centered around Varanasi

Significant political and religious hub

Later Dominant Kingdoms:

Kuru and Panchala merged into Kuru-Panchala region

After their decline: Kosala, Kasi, Videha, Magadha, Anga, Vanga rose

Eventually evolved into Mahajanapadas (great kingdoms) by c. 600 BCE

Key Political Transformations:

From tribal polity to territorial monarchy

From elective leadership to hereditary kingship

From participatory assemblies to monarchical control

From voluntary gifts to systematic taxation

Integration of religion and politics through rituals

Society and Varna System

Early Vedic Period Society

General Character:

Tribal and kinship-based social organization

Patriarchal society with eldest male as head of family (Kutumba)

Relatively egalitarian compared to later period

Free society with considerable social mobility

Social Units (Hierarchy):

Kula (कुल): Family – basic social unit

Grama (ग्राम): Village – group of related families

Vish (विश्): Clan

Jana (जन): Tribe – highest unit

Social Division – Flexible Varna:

The early Varna system was based on occupation rather than birth:

Four Varnas:

Brahmins (ब्राह्मण):

Priests, scholars, teachers

Performed sacrifices and rituals

Preserved Vedic knowledge

Expected to learn and teach Vedas

Kshatriyas/Rajanyas (क्षत्रिय/राजन्य):

Warriors, tribal chiefs, rulers

Protected the tribe

Led in warfare

Assumed importance due to military role

Vaishyas (वैश्य):

Agriculturists, cattle-rearers, traders

Engaged in productive economic activities

Shudras (शूद्र):

Appeared later in Early Vedic period

Mentioned in 10th Mandala of Rigveda (later addition)

Initially had undefined role

Key Features:

Flexible – based on profession, NOT rigid by birth

Social mobility possible – could change varna

No concept of untouchability

Three upper varnas received Dwija (twice-born) status through Upanayana ceremony

Status of Women in Early Vedic Period:

High Status and Rights:

Educational Rights:

Women had access to Vedic education

Girls educated along with boys

Received Upanayana (sacred thread) ceremony enabling entry into Gurukul system

Two categories of educated women:

Sadyavadhu: Pursued education until marriage

Brahmavadinis: Never married, continued studying and teaching throughout life

Studied Vedas, Vedangas, fine arts

Notable Female Scholars:

Gargi: Engaged in philosophical debates

Maitreyi: Renowned scholar

Lopamudra: Composed hymns in Rigveda

Apala, Indrani, Ghosha: Vedic scholars

Visvavara: Leading woman of Rig Vedic times

Political Participation:

Women allowed to attend Sabha and Samiti (political assemblies)

Could participate in decision-making

Social Freedom:

Freedom to choose husbands

Swayamvara system allowed women to select partners

Marriageable age: 16-17 years (no child marriage)

Could marry late if they wished

Never observed purdah (veil)

Property Rights:

Unmarried daughters shared in father’s property

Daughter had full legal rights to father’s property in absence of son

Possessed property rights and could inherit and manage “Stridhan” (gifts, dowries, personal earnings)

Family Status:

Enjoyed complete freedom in domestic life

Treated as Ardhangini (equal half)

Considered supreme in household matters

Husband consulted wife on financial matters

Religious Rights:

Participated in religious ceremonies with husband

Woman considered necessary partner in religious life

“Man without woman considered inadequate person”

Limitations:

Divorce not permissible

Widow had no right to inherit deceased husband’s property (though spinster could inherit from father)

Niyoga system allowed childless widow to marry younger brother of deceased husband

Later Vedic Period Society

General Transformation:

Transition from pastoral to settled agricultural society

Urban centers started emerging

Social stratification became more pronounced

Society became more hierarchical and complex

Rigid Varna System:

Four-Fold Division Solidified:

Brahmins (ब्राह्मण):

Highest status in social hierarchy

Wore white symbolizing purity

Performed sacrifices, received gifts (dakshina)

Gained influence by legitimizing kings’ rule

Alliance with kings strengthened Brahmanical order

Kshatriyas (क्षत्रिय):

Second rank in hierarchy

Warriors, rulers, administrators

Wore elaborate attire with vibrant colors reflecting status

King usually a Kshatriya

Office becoming hereditary

Vaishyas (वैश्य):

Third position in hierarchy

Farmers, merchants, traders

Generated wealth and commerce

Balanced practicality with modest adornment

Shudras (शूद्र):

Lowest position in hierarchy

Laborers, artisans, service providers

Sole function: Serve the upper three varnas

Excluded from Dwija (twice-born) status

No access to Vedic learning

Wore simpler, coarser fabrics

Key Changes:

Varna became rigid and birth-based

Social mobility severely restricted

Untouchability concept emerged

Rise of Jatis (sub-castes) based on occupational specialization

Textual References:

Purusha Sukta (Rigveda 10.90):

Describes four varnas emerging from cosmic being (Purusha):

Brahmins from mouth

Kshatriyas from arms

Vaishyas from thighs

Shudras from feet

Later Texts:

Manusmriti: Made varna distinctions more rigid and defined rules

Dharmasutras: Codified varna duties and restrictions

Introduction of Gotra System:

Developed in Later Vedic period

People with common gotra descended from common ancestor

No marriage between members of same gotra

Ashrama System (Four Life Stages):

Initially three stages, later expanded to four:

Brahmacharya (ब्रह्मचर्य): Student life, celibacy, learning

Grihastha (गृहस्थ): Householder life, family, economic activities

Vanaprastha (वानप्रस्थ): Forest-dwelling, gradual withdrawal

Sannyasa (संन्यास): Renunciation, added later

Combined with varna, known as Varna-Ashrama system

Declining Status of Women:

Major Changes:

Educational Decline:

Women’s access to education became limited

Vedic education restricted to religious songs and poems necessary for rituals

Later prohibited from Vedic recitation

Social Restrictions:

Women no longer permitted to sit in Sabha (political assembly)

Lost political participation rights

Growing restrictions on freedom

Property Rights:

Continued to have limited property rights

No right for widow to inherit husband’s property

Period of Transition:

Status began declining from high position in Early Vedic period

Would worsen further in Post-Vedic and Medieval periods

Economic Structure

Early Vedic Economy

Primary Character:

Predominantly pastoral economy centered on cattle rearing

Agriculture played supplementary role

Semi-nomadic lifestyle

Cattle as Wealth:

Cattle (go) were the primary measure of wealth

Prosperity determined by number of cattle owned

Frequent cattle raids between tribes

Terms for war often related to cattle (gavishti – search for cows)

Agricultural Practices:

Limited agriculture with cultivation of:

Barley (yava)

Wheat

Limited mention of rice

Simple farming techniques

Use of wooden ploughs

Livestock:

Cattle (cows, bulls, oxen)

Horses (highly valued)

Goats

Sheep

Trade and Exchange:

Primarily barter system

Cattle used as medium of exchange

No coinage in circulation

Nishka: Gold ornament used occasionally for exchange

Limited trade activities

Occupations:

Cattle herding (primary)

Basic agriculture

Simple crafts

Warrior activities

Gifts to Raja:

Bali (बलि): Voluntary gifts of cattle and goods

Occasional raids supplemented tribal resources

Later Vedic Economy

Primary Character:

Transformation to agrarian economy as primary base

Settled agricultural communities

Significant expansion of trade and commerce

Agricultural Revolution:

Iron Technology Impact:

Introduction of iron tools (Shyam Ayas – black metal) revolutionized agriculture

Iron implements enabled:

Clearing forests: Iron axes cleared Gangetic forests for cultivation

Ploughing: Iron ploughshares cultivated vast tracts

Harvesting: Iron sickles for efficient reaping

Crops Cultivated:

Rice (vrihi): Became important in Gangetic plains

Barley (yava)

Wheat (godhuma)

Vegetables and fruits

Legumes

Agricultural Operations:

Sowing, ploughing, reaping, threshing mentioned in texts

More systematic and extensive cultivation

Metallurgy and Crafts:

Metal Working:

Iron (Shyam Ayas): Extensively used for tools and weapons

Copper (Loh Ayas): Continued use from Early Vedic period

Bronze: Alloy of copper and tin for durable implements

Gold and Silver: For jewelry and ornaments

Craft Specialization:

Pottery: Multiple types including Painted Grey Ware

Metallurgy: Smelting and forging

Textiles: Weaving, spinning

Carpentry: Using iron tools (saws, chisels, hammers, nails)

Tanning: Leather working

Tool making: Various occupations emerged

Trade and Commerce:

Expansion:

Urban centers became hubs of economic activities

Development of trade networks

Growth of commercial activities

Medium of Exchange:

Introduction of coins as currency

Krishnala: Gold and silver coins mentioned

Barter system continued alongside monetary exchange

Economic Activities:

Local and inter-regional trade

Specialized markets (hatta)

Exchange of agricultural surplus

Trade in crafts and manufactured goods

Revenue System:

Systematic Taxation:

Bali: Originally voluntary gifts, became expected tributes

Bhaga: Regular tax share from agricultural produce

Taxes on agriculture made systematic with settled farming

Collected by officials like Sangrihitri (treasurer)

Other Income Sources:

Gifts from subjects

Tributes from conquered territories

War booty

Art and Culture

Material Culture

Pottery:

Early Vedic Period:

Ochre Coloured Pottery (OCP)

Red slip with ochre appearance

Black painted designs

Forms: jars, storage jars, bowls, basins

Later Vedic Period:

Painted Grey Ware (PGW)

Grey colored, wheel-made, thin-walled

Geometric designs in red or black paint

Characteristic forms: shallow dishes, deep bowls

Fine fabric and excellent firing

Black and Red Ware (BRW)

Black Slipped Ware

Red Ware

Clothing and Dress:

Fabrics and Materials:

Cotton: Gained prominence in later Vedic period

Wool: From sheep, spun and woven

Silk: Rare, reserved for affluent

Natural dyes: From plants, minerals, insects

Leather and fur: Utilitarian purposes among lower classes

Men’s Clothing:

Vasa/Dhoti (वस):

Lower garment

Long cloth draped around waist and legs

Regional variations in draping style

Adhivasa/Uttariya (अधिवस/उत्तरीय):

Upper garment

Draped over shoulders or upper body

Sometimes covered head

Significant in rituals and daily life

Kanchuka (कञ्चुक):

Sleeveless jacket

Worn by elite

Men’s Ornaments:

Turbans

Earrings (Kundala)

Necklaces (Kantha)

Bangles

Emblems of status and wealth

Women’s Clothing:

Sari:

Versatile length of cloth

Various draping styles

Often covered head

Regional customs dictated styles

Stanapatta:

Chest band

Covered upper body

Kanchuka/Blouse:

Favored by upper classes

Women’s Jewelry:

Bangles

Anklets (Nupura)

Nose rings

Necklaces (Kantha)

Armlets (Keyura)

Earrings (Kundala)

Sindoor (vermillion) for married women

Bindi (forehead mark) for married women

Conveyed marital status and social position

Materials for Jewelry:

Gold

Silver

Bronze

Ivory

Sankha (mother of pearl)

Pearls

Semi-precious stones

Terracotta

Conch shells

Weapons:

Early Vedic Period (Copper Age):

Copper weapons (Loh Ayas)

Bronze weapons and implements

Made through:

Casting metal into moulds

Cutting metal sheets

Hammering for shape

Karmar (blacksmith) crafted implements

Later Vedic Period (Iron Age):

Iron weapons (Shyam Ayas) at larger scale

Stronger and sharper than copper/bronze

Types of Weapons:

Bows: Various types from wood and bamboo

Arrows (Sarya, Sari, Isu): Made from copper, iron, bone

Triangular, leaf-shaped, cylindrical shapes

Some with tangs and holes

Swords

Armors and shields

Spears

Copper axes and implements

Tools and Implements:

Agricultural Tools:

Ploughs with iron heads

Sickles (iron)

Hoes (iron)

Axes (iron, for forest clearing)

Craft Tools:

Saws

Chisels

Hammers

Nails

Tongs

Bone tools (needles, combs, moulds)

Metals in Use:

Early Period:

Copper: Extensively used

Sources: Khetri mines (Rajasthan), Baluchistan

Used for agriculture, tools, utensils, water purification

Bronze: Copper-tin alloy (8-12% tin)

Greater hardness and durability

Weapons, tools, statues

Gold: Ornaments and exchange

Silver: Jewelry and coins

Later Period:

Iron: Revolutionary impact

Referred as ayas in Yajur Veda and Brahmanas

Enabled agricultural expansion

Superior weapons and tools

Housing:

Early Vedic: Simple thatched huts, mud houses

Later Vedic:

Square and rectangular houses

Use of mud bricks and burnt bricks

More advanced construction techniques

Evidence of paved roads and drainage systems at some sites

Impact on Indian Society: Analysis

Positive Contributions

1. Religious and Spiritual Foundation:

Foundational texts: Vedas form the basis of Hindu philosophy and spirituality

Philosophical concepts: Introduction of Brahman, Atman, Karma, Moksha shaped Indian worldview

Ritual traditions: Vedic yajnas and rituals continue in modified forms

Yoga and meditation: Upanishadic practices influence modern spiritual movements

Ethical framework: Concepts of Dharma, righteousness, and duty guide moral conduct

2. Intellectual and Educational Legacy:

Gurukul system: Ancient education model honored worldwide

Scientific contributions:

Astronomy and mathematics

Medicinal knowledge (Ayurveda foundations)

Geometry in altar construction

Linguistic heritage: Sanskrit as classical language and mother of many Indian languages

Preservation of knowledge: Oral tradition maintaining textual integrity for millennia

3. Social Organization:

Family structure: Emphasis on joint family and kinship bonds

Community values: Concepts of collective welfare and social responsibility

Ashrama system: Life-stage framework providing social structure

Festivals and celebrations: Vedic traditions form basis of Hindu festivals like Diwali, Holi

4. Cultural Continuity:

Unbroken tradition: India survived as civilization due to Vedic cultural roots

Art and music: Samaveda as origin of Indian classical music

Architecture: Temple architecture evolved from Vedic altar construction

Cultural practices: Many modern customs trace to Vedic period

5. Environmental Ethics:

Reverence for nature: Worship of natural forces fostered environmental consciousness

Concept of interconnected universe: All life seen as connected

Ritual practices: Like yajña incorporated ecological awareness

Negative Impacts and Criticisms

1. Social Inequality – Caste System:

Birth-Based Hierarchy:

Originally flexible varna system became rigid caste system

Birth determined social status, not merit or occupation

Created entrenched social divisions that persist today

Discrimination and Exclusion:

Untouchability: Certain groups ostracized completely

Limited social mobility and opportunity

Shudras denied education and Vedic learning

Inter-caste mixing prohibited

Modern Persistence:

Caste discrimination continues despite legal prohibition

Affects education, employment, marriage

Source of social tension and violence

Colonial era worsened misunderstanding and rigidified caste

2. Gender Inequality – Patriarchal Structure:

Declining Status of Women:

From high status in Early Vedic to restrictions in Later Vedic

Loss of educational rights

Exclusion from political participation

Property rights limited

Modern Legacy:

Deep-rooted patriarchal structure influences modern India

Gender bias in education and employment

Preference for male children

Expectations limiting women’s autonomy

Normalization of gender-based violence

Slow progress in dismantling patriarchy

3. Religious Orthodoxy:

Brahmanical Dominance:

Priestly monopoly over religious knowledge and rituals

Exclusion of lower castes from spiritual practices

Ritualism became complex and expensive

Created religious hierarchy

Anti-Scientific Tendencies:

Some interpretations discouraged empirical inquiry

Overemphasis on tradition over innovation

Vedic revivalism sometimes promotes pseudo-science

Stunted development of sciences in certain periods

4. Social Fragmentation:

Varna system led to social fragmentation

Anti-communitarian life: Divisions weakened social cohesion

Group identities became rigid and exclusive

Conflicts between communities

5. Economic Implications:

Occupational restrictions limited economic mobility

Hereditary professions prevented optimal talent utilization

Agricultural society became static in later periods

6. Modern Challenges:

Adaptation Issues:

Fast-paced modern life overshadows traditional practices

Globalization challenges cultural preservation

Commercialization of religious practices dilutes authenticity

Urban migration disrupts traditional social structures

Reform Movements:

19th-20th century reformers (Raja Ram Mohan Roy, B.R. Ambedkar) challenged caste discrimination

Constitutional provisions against caste discrimination

Ongoing efforts for social justice and equality

Balanced Perspective

Positive Adaptations:

Modern integration of Vedic values with contemporary life

Eco-friendly practices in rituals show environmental awareness

Mindfulness and holistic health align with modern wellness

Festivals bring communities together

Areas Needing Reform:

Caste system: Requires complete dismantling through education and social change

Gender equality: Need cultural attitude shift and policy reforms

Religious practices: Balance tradition with rationality

Education: Integrate valuable Vedic knowledge without revivalism

Continuing Relevance:

Vedic philosophy offers insights for modern challenges

Spiritual practices provide meaning in materialistic age

Ethical teachings relevant for contemporary society

Cultural heritage provides continuity and identity

Need to preserve positive aspects while eliminating discriminatory practices

Conclusion

The Vedic Age represents a formative period that profoundly shaped Indian civilization. While it contributed immensely to philosophy, spirituality, literature, and culture, it also established social hierarchies that became sources of inequality and discrimination. Modern India must preserve the valuable philosophical and cultural heritage while actively dismantling oppressive social structures like caste discrimination and patriarchy. The challenge lies in maintaining cultural continuity while embracing progressive values of equality, justice, and human dignity.

Read More: Ancient India Notes

Discover more from Simplified UPSC

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.