India’s Judicial Appointments Framework: Collegium System and NJAC

Contents

Collegium System and NJAC: Understanding India’s Judicial Appointments Framework

The appointment of judges to India’s superior judiciary remains one of the most debated topics in constitutional law. Two competing frameworks have shaped this discourse: the Collegium System, which has been in place since 1993, and the National Judicial Appointments Commission (NJAC), which was struck down just months after its implementation. Understanding these systems is crucial for anyone preparing for the UPSC examination or seeking to comprehend how India’s judicial independence is preserved.

What is the Collegium System?

The Collegium System is a process through which judges of the Supreme Court and High Courts are appointed and transferred. Despite its critical role in shaping India’s judiciary, it is notably not mentioned anywhere in the Constitution. Instead, it has evolved entirely through judicial interpretation and precedent, emerging from what are popularly known as the “Judge Cases.”

The Collegium operates on a fundamental principle: judges are appointed by judges themselves, thereby insulating the judiciary from executive interference. This system aims to preserve the independence of the judiciary, one of the cornerstone principles of India’s constitutional framework.

Constitutional Provisions Governing Judicial Appointments

Two key constitutional articles provide the legal foundation for judicial appointments:

Article 124 stipulates that the President shall appoint Supreme Court judges after consultation with the Chief Justice of India and such other judges of the Supreme Court and High Courts as deemed necessary. Article 217 similarly provides for High Court judge appointments by the President after consultation with the Chief Justice of India, the Governor of the state, and the Chief Justice of the High Court concerned.

However, the interpretation of the word “consultation” in these articles has been the subject of intense judicial scrutiny and constitutional debate.

The Evolution of the Collegium System: The Three Judge Cases

The Collegium System did not emerge overnight. Instead, it evolved through three landmark Supreme Court judgments, collectively referred to as the “Three Judge Cases” or “Judges Cases.”

First Judges Case (SP Gupta vs. Union of India, 1981)

In this foundational judgment, the Supreme Court held that the term “consultation” under Articles 124 and 217 did not mean “concurrence” or binding agreement. Rather, it meant mere advice. This interpretation granted the executive significant discretionary power in judicial appointments, with the government retaining the final decision-making authority.

However, this judgment was heavily criticized for undermining judicial independence by allowing executive dominance in appointments. The judgment essentially gave the executive a decisive hand in choosing judges, which many legal scholars viewed as an erosion of the judiciary’s autonomy.

Second Judges Case (Supreme Court Advocates-on-Record Association v. Union of India, 1993)

Twelve years later, a nine-judge bench of the Supreme Court reversed the First Judge Case in a landmark decision. This case fundamentally altered the landscape of judicial appointments in India.

The Supreme Court held that “consultation” under Articles 124 and 217 actually meant “concurrence”—the opinion of the Chief Justice of India became binding on the government. This judgment established that:

The Chief Justice of India must consult with senior judges before making recommendations

The CJI’s collective opinion, formed in consultation with senior judges, is binding

The government must accept the CJI’s recommendation

This decision crystallized the Collegium System as we know it today. The Second Judge Case essentially transferred appointment authority from the executive to the judiciary, thereby preserving judicial independence. At this stage, the Collegium consisted of the Chief Justice of India and the two senior-most judges of the Supreme Court.

Third Judges Case (In Re: Appointment & Transfer of Judges, 1998)

In 1998, the President referred a question to the Supreme Court seeking clarity on the primacy accorded to the Chief Justice of India in judicial appointments. The Supreme Court’s response further strengthened the Collegium system.

The Court unanimously held that:

The Collegium should be expanded from three members to five members

It should consist of the Chief Justice of India and the four senior-most judges of the Supreme Court

Even if two judges give an adverse opinion, the recommendation should not be sent to the government

This expansion was intended to provide a broader perspective and greater institutional legitimacy to the appointment process. The three-member Collegium was deemed insufficient to represent the institutional opinion of the judiciary comprehensively.

Composition and Functioning of the Collegium

The Supreme Court Collegium currently comprises:

The Chief Justice of India (CJI) – Head of the Collegium

Four senior-most judges of the Supreme Court

This five-member body is responsible for:

Recommending appointments of Supreme Court judges

Recommending appointments of Chief Justices of High Courts

Recommending transfers of High Court judges between different High Courts

The Collegium follows a procedure outlined in the Memorandum of Procedure (MoP) adopted in 1999, which has been updated over time. The government can raise objections to recommendations and request reconsideration, but if the Collegium reiterates its recommendation, the government is legally bound to accept it.

High Court Collegium: Structure and Procedure

The High Court Collegium operates with a slightly different composition and follows specific procedures outlined in the MoP:

Composition:

Chief Justice of the High Court

Four senior-most judges of that High Court

Procedure for HC Judge Appointments:

The High Court Collegium identifies suitable candidates for judicial appointments

The Collegium’s recommendation is sent to the Chief Justice of India

The Supreme Court Collegium reviews and approves the recommendation

The recommendation is forwarded to the Central Government

The government conducts a background check through the Intelligence Bureau (IB)

The government may raise objections or seek clarification

If the Collegium reiterates its recommendation, the government must appoint the judge

The High Court Collegium has primacy in assessing the suitability of local candidates, as members are familiar with the judicial quality, work ethic, and personal integrity of potential appointees within their jurisdiction.

Criticisms of the Collegium System

Despite its role in safeguarding judicial independence, the Collegium system has faced significant criticism from various quarters, including judges, legal scholars, civil society, and former chief justices of India.

Lack of Transparency

The most prominent criticism is the opaque functioning of the Collegium. Collegium decisions are made behind closed doors, with no publicly available criteria, detailed reasoning, or justification for appointments or rejections. Until 2017, Collegium resolutions were not published at all. Even after publishing began, the resolutions often lack substantive reasoning, leaving the decision-making process shrouded in mystery.

This opacity fuels public distrust and raises questions about whether decisions are made on merit or based on personal networks and favoritism.

Absence of Accountability

The Collegium operates without formal external oversight or accountability mechanisms. Unlike other constitutional bodies with built-in checks and balances, the Collegium remains entirely self-regulated. There is:

No external review mechanism

No grievance redressal system

No mechanism for judicial review of Collegium decisions

No representation from stakeholders such as the legislature, executive, bar associations, or civil society

Allegations of Favoritism and Nepotism

The closed nature of the Collegium has invited persistent allegations of nepotism, favoritism, and regional bias. Critics argue that judicial appointments may be influenced by personal relationships and networks rather than pure merit. Notable judges, including Justice J. Chelameswar, who dissented in the NJAC case, publicly criticized the system, stating it was “absolutely opaque and inaccessible both to the public and history.”

Lack of Diversity

The Collegium system has been criticized for under-representation of women judges, judges from marginalized communities, and judges with diverse professional backgrounds. The senior-most selection criterion, while ensuring experience, may inadvertently perpetuate historical biases and limited diversity.

Constitutional Ambiguity

Critics argue that the Collegium system is not constitutionally mandated and has entirely emerged through judicial precedent. This creates constitutional ambiguity and raises questions about whether judges have overstepped their authority by creating an appointment system not explicitly provided for in the Constitution.

The National Judicial Appointments Commission (NJAC): An Attempted Reform

Recognizing the deficiencies of the Collegium system, the Indian government attempted a significant institutional reform through the 99th Constitutional Amendment Act, 2014, which established the National Judicial Appointments Commission.

Why Was NJAC Introduced?

The government argued that the Collegium system lacked:

Transparency and accountability

Broader participation and representation

Objective criteria for appointments

Democratic legitimacy

The NJAC was proposed as a more inclusive, transparent, and accountable mechanism for judicial appointments that would balance judicial independence with broader stakeholder participation.

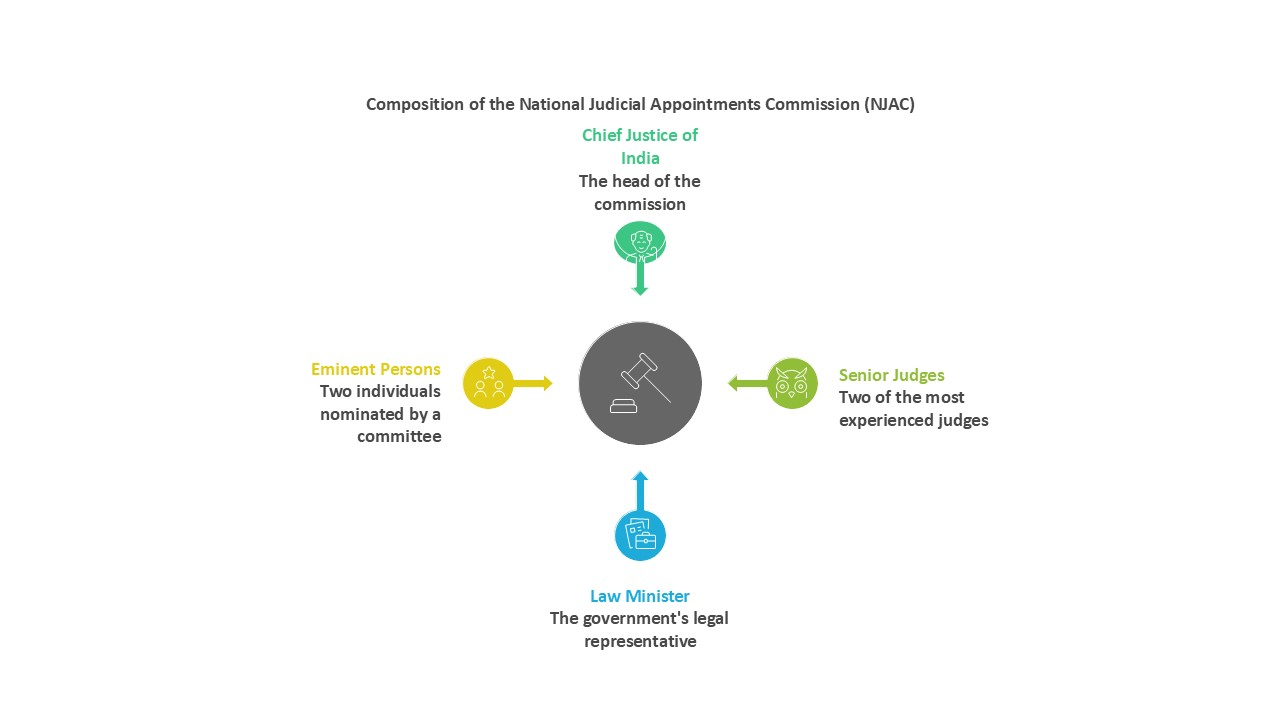

Composition of NJAC

The NJAC was designed to be a six-member constitutional body comprising:

Chief Justice of India – Head of the Commission

Two senior-most judges of the Supreme Court

Union Minister of Law and Justice

Two eminent persons – nominated by a committee consisting of the Prime Minister, the Chief Justice of India, and the Leader of the Opposition (or Leader of the single largest opposition party if no official opposition leader existed)

Key Features of NJAC

The NJAC Act provided for:

Merit-based selection: Candidates would be selected based on merit, seniority, judicial experience, and integrity

Broader consultation: The Commission would consult state authorities, bar associations, and other stakeholders

Veto provision: If any two members of the NJAC disagreed with a recommendation, it could not be forwarded

Reconsideration: The President could request reconsideration of recommendations

Why Was NJAC Struck Down?

The NJAC faced immediate constitutional challenge. The Supreme Court Advocates-on-Record Association (SCAORA) filed a petition challenging the constitutionality of the 99th Amendment. This case came to be known as the Fourth Judges Case.

The Supreme Court, in a 4:1 majority judgment in October 2015, declared both the NJAC Act and the 99th Amendment unconstitutional and null and void. Justice J.S. Khehar delivered the majority judgment.

Grounds for Striking Down NJAC:

Violation of Basic Structure Doctrine: The Court held that the NJAC violated the “basic structure” of the Constitution, particularly the principle of judicial independence and separation of powers

Erosion of Judicial Primacy: The NJAC structure gave equal power to the executive and judiciary in the appointment process. The inclusion of the Law Minister and eminent persons (who could be influenced by the executive) threatened judicial primacy

Problematic Veto Power: The veto provision allowed any two members to block a unanimous recommendation by the CJI and senior judges. This meant that the “eminent persons” could exercise disproportionate power, potentially blocking appointments even when all judges unanimously agreed

Vagueness on “Eminent Persons”: The NJAC Act did not define who qualified as “eminent persons” or specify their qualifications. Their selection would be entirely at the discretion of the nominating committee, making it vulnerable to political influence

Supersession Risk: The requirement that the CJI be found “fit” by the Commission opened the possibility of superseding senior judges, undermining the seniority-based system that protected judicial independence

Separation of Powers: The Court emphasized that the appointment of judges is fundamentally a judicial function, and allowing the executive equal say would blur the separation between the judiciary and executive, contrary to constitutional principles

Collegium vs. NJAC: A Comparative Analysis

| Aspect | Collegium System | NJAC |

|---|---|---|

| Constitutional Basis | Evolved through judicial precedent (not constitutionally mandated) | Established through 99th Constitutional Amendment |

| Composition | 5 members: CJI + 4 senior judges | 6 members: CJI + 2 judges + Law Minister + 2 eminent persons |

| Primacy | Judicial primacy maintained; executive cannot override collegium reiterations | Shared power between judiciary and executive |

| Appointment Power | Judges appoint judges | Mixed body with executive participation |

| Transparency | Opaque; limited reasoning provided | Proposed to be more transparent |

| Accountability | No external accountability mechanism | Limited accountability |

| Executive Role | Verification through IB; can seek reconsideration once | Equal participant in commission |

| Diversity Consideration | Limited diversity mechanisms | Proposed broader consultation |

| Judicial Independence | Strongly protected | Supreme Court deemed threatened |

| Status | Currently operational | Struck down (2015); unconstitutional |

Dissent and Alternative Perspectives

While the majority of the Supreme Court struck down NJAC, there was a notable dissent that offers valuable insights into the debate.

Justice Jasti Chelameswar’s Dissent acknowledged that the Collegium system suffered from lack of transparency, accountability, and objectivity. He argued that the NJAC, despite its flaws, represented an attempt to address these deficiencies. He believed that the concerns about judicial independence were overstated, particularly given that the CJI retained a significant voice in the commission.

Justice Kurian Joseph, while concurring with the majority judgment striking down NJAC, explicitly stated that “the present collegium system lacks transparency, accountability and objectivity.” He suggested that these deficiencies were “curable” through internal reforms rather than replacing the system entirely.

Recent Concerns and the Revival Debate

Recent controversies have reignited the NJAC debate. The Justice Yashwant Varma incident (involving a cash-in-house controversy) led to calls for reviving NJAC. Vice President Jagdeep Dhankhar suggested that greater executive participation through NJAC might have prevented such controversies.

However, the Supreme Court has consistently maintained that the collegium system is the constitutionally sound mechanism for preserving judicial independence, emphasizing the need for internal reforms rather than structural overhaul.

Potential Reforms to the Collegium System

Rather than scrapping the Collegium, many judicial observers and constitutional experts advocate for internal reforms that maintain judicial independence while addressing transparency concerns:

Codification of Criteria: Establish clear, objective criteria for judicial appointments based on merit, experience, integrity, and potential

Enhanced Transparency: Publish reasoned Collegium resolutions explaining the rationale for appointments and rejections

Diversity Initiatives: Implement mechanisms to ensure adequate representation of women judges and judges from marginalized communities

Stakeholder Consultation: Formally include consultations with bar associations and civil society in the appointment process

Prescribed Timelines: Enforce strict timelines for appointments to reduce pending vacancies

Appeal Mechanism: Establish a limited review mechanism for grievances related to judgmental decisions (without compromising independence)

Enhanced Background Verification: Strengthen the background verification process to identify unsuitable candidates early

Conclusion

The Collegium System and NJAC debate represents a fundamental tension in constitutional governance: the need to preserve judicial independence while ensuring transparency, accountability, and democratic participation in institutional decision-making.

While the Collegium System, despite its flaws, has proven effective in insulating the judiciary from executive interference and maintaining the independence of judicial appointments, its opaque functioning and lack of accountability remain significant concerns. The Supreme Court’s rejection of NJAC demonstrated its commitment to judicial independence, but the judgment also acknowledged the need for reforms.

The path forward likely lies not in replacing the Collegium with a commission that risks executive dominance, but in reforming the Collegium itself—maintaining its core strength of preserving judicial independence while introducing greater transparency, accountability, and inclusivity. Such balanced reforms could strengthen public trust in the judiciary while safeguarding the constitutional principle of separation of powers.

Discover more from Simplified UPSC

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.