Linkages Between Development and Spread of Extremism in India

Contents

Linkages Between Development and Spread of Extremism in India: A Comprehensive Analysis

Introduction

The nexus between inadequate development and the proliferation of extremism represents one of India’s most persistent internal security challenges. This relationship is not merely correlative but deeply causal—underdevelopment creates the structural conditions, grievances, and marginalization that extremist movements exploit for recruitment and ideological propagation. Understanding this linkage is critical for developing effective counter-extremism strategies that combine security operations with developmental interventions.

1. Definitions and Explanations: Core Concepts

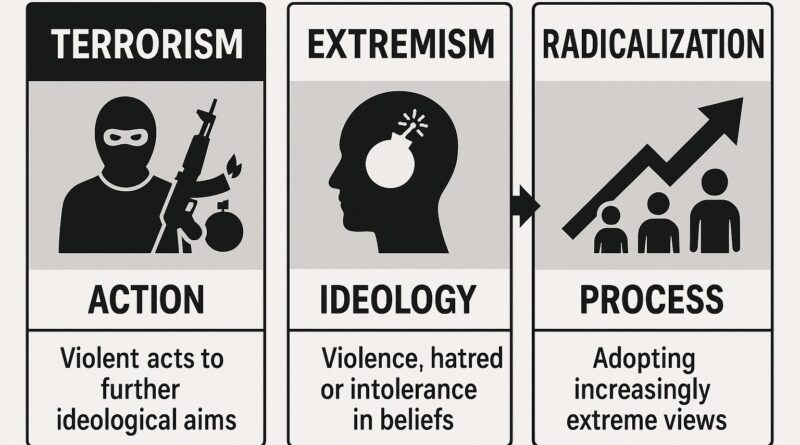

1.1 Terrorism

Terrorism is defined as the use of violent action or threat thereof, designed to influence government or intimidate the public to advance a political, religious, or ideological cause. According to the UK Terrorism Act 2006, terrorism encompasses actions that endanger lives, involve serious violence against persons, cause serious property damage, create serious risks to public health and safety, or disrupt critical systems. Crucially, terrorism is characterized by its action dimension—it represents the violent manifestation of extremist ideology through organized attacks on civilians and state infrastructure.

1.2 Extremism

Extremism represents the ideological substrate underlying terrorism. It is the promotion or advancement of ideologies based on violence, hatred, or intolerance aimed at negating fundamental rights of others, undermining democratic institutions, or creating permissive environments for violent action. Unlike terrorism, extremism operates at the belief level and need not necessarily involve direct violence, though it creates the intellectual justification for violent acts. Extremism is “linked to political, social, or religious beliefs and ideas” and represents the worldview that rationalizes terrorist actions.

1.3 Radicalization

Radicalization is the process by which individuals or groups progressively adopt increasingly extreme ideological positions. It is a transformative journey where persons gradually accept the use of violence—including terrorism—to achieve political, social, or religious objectives. Radicalization operates at multiple levels: the individual develops conviction in radical beliefs; the group reinforces these beliefs through collective identity; and the broader social context of grievance and marginalization provides the enabling environment. McCauley and Moskalenko characterize radicalization as “increasing extremity of beliefs, feelings, and behaviors in directions that increasingly justify intergroup violence.” The critical distinction is that radicalization is procedural—it describes how individuals transition from conventional thinking to violent extremism.

Key Distinctions

| Aspect | Terrorism | Extremism | Radicalization |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nature | Action/Behavior | Ideology/Belief | Process |

| Manifestation | Violent attacks on civilians/state | Ideological worldview promoting violence | Gradual adoption of extreme beliefs |

| Focus | Material violence | Intellectual justification | Psychological transformation |

| Outcome | Casualties, infrastructure damage | Ideological framework | Individual/group indoctrination |

2. India’s Internal Security Situation: Current Status and Emerging Threats

2.1 Overall Landscape

India’s internal security environment in 2025 presents a paradox: significant tactical successes against traditional insurgencies coexist with emerging, technology-enabled threats that challenge conventional security frameworks. The country faces a hybrid threat matrix encompassing left-wing extremism, regional insurgencies, cross-border terrorism, and increasingly, online radicalization amplified by artificial intelligence.

2.2 Key Security Challenges

Multiple Insurgency Fronts: India manages concurrent insurgencies across geographically dispersed regions—the Red Corridor (left-wing extremism), the Northeast (ethnic-based insurgencies), Jammu-Kashmir (Pakistan-sponsored militancy), and remnants of the Punjab separatism. This simultaneity strains security resources and prevents comprehensive stabilization.

Development-Security Nexus: A defining characteristic of India’s security crisis is the direct correlation between underdevelopment indices and insurgency intensity. States with low Human Development Index (HDI)—particularly Bihar (0.621), Uttar Pradesh (0.649), Madhya Pradesh (0.656), Chhattisgarh (0.664), and Jharkhand (0.667)—simultaneously host the most severe insurgent activity. These regions score comparably to African nations like Congo, Kenya, and Ghana on HDI metrics, indicating profound structural marginalization.

Youth Alienation and Unemployment: Approximately 70% of Jammu and Kashmir’s population is under age 35, yet the region faces among India’s highest unemployment rates. Kashmir’s alienation index among unemployed youth (57.59) is significantly higher than employed youth (45.27), creating a generation susceptible to militancy recruitment. Similar patterns emerge in the Northeast and LWE-affected areas.

Online Radicalization and AI-Amplified Extremism: A critical emerging threat involves algorithm-driven platforms and generative AI enabling extremist groups to customize multilingual propaganda and target emotional vulnerabilities with unprecedented precision. The November 2025 D-6 terror case exemplified this pattern—young recruits were radicalized through online networks before linkage to foreign handlers.

Structural Security Gaps: Coordination between central and state agencies remains inconsistent, particularly across jurisdictions. Most district police units operate understaffed and overburdened with routine duties, limiting capacity for specialized counter-extremism work. Procurement procedures for advanced equipment (drone detection, cyber tools) move slowly through administrative layers.

3. Left-Wing Extremism (LWE): Development Deprivation as Catalyst

Left-wing extremism, rooted in Maoist ideology originating from the 1967 Naxalbari uprising in West Bengal, represents India’s most persistent internal security challenge, with direct causation traceable to developmental failure and tribal marginalization.

Structural Causes: LWE proliferates in regions characterized by severe poverty, land alienation, and tribal displacement. The Red Corridor—spanning 10 states across Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, Odisha, and Andhra Pradesh—encompasses areas where 25% of populations live below the poverty line. Land acquisition for dams, mining, and industrial projects has systematically displaced tribal communities without adequate rehabilitation, converting them into “encroachers on their own lands.” Constitutional safeguards for tribal autonomy remain largely unimplemented, creating systematic grievance.

Demographic Targeting: Naxalites have deliberately redirected recruitment toward marginalized tribal and Dalit populations in underdeveloped regions, exploiting their exclusion from mainstream economic opportunities and governmental protection.

Quantified Progress Against Development: Recent government initiatives demonstrate the inverse relationship—development interventions correlate with LWE decline. LWE-affected districts have reduced from 126 (2018) to 38 (2024). Violence incidents fell 81% from 1,936 (2010) to 374 (2024), while deaths declined 85% from 1,005 (2010) to 150 (2024). Over 8,000 Naxalites have abandoned insurgency in 10 years. Chhattisgarh’s most-affected districts (Bijapur, Kanker, Narayanpur, Sukma) continue experiencing violence because development infrastructure remains inadequate. The causal mechanism is clear: insufficient development sustains grievance and recruitment pools.

4. North-East Insurgency: Identity, Development Neglect, and Regional Marginalization

North-Eastern insurgency, distinct from LWE though similarly rooted in developmental deprivation, emerges from ethnic fragmentation, historical colonial neglect, and persistent economic marginalization across 200+ ethnic groups.

Development-Insurgency Correlation: The Northeast hosts 80+ active insurgent groups (NSCN, ULFA, NDFB, PLA) exploiting ethnic identities while resource-rich regions paradoxically suffer unemployment, poor infrastructure, and low industrialization. Insurgency functions as an informal “economic industry” for marginalized youth lacking legitimate livelihood. Porous 5,500 km borders with five countries enable arms supply and cross-border sanctuaries, but recruitment fundamentally derives from economic desperation and political alienation.

Recruitment Patterns: ULFA deliberately targeted remote villages and marginalized indigenous communities after urban educated classes rejected its methods. Paresh Baruah’s faction conducted massive recruitment drives in economically backward districts (Dibrugarh, Tinsukia, Lakhimpur, Nalbari) where developmental services are minimal. ULFA collected Rs. 5 billion through extortion and kidnapping—revenue sources substituting absent legitimate economic opportunities.

Statistical Decline Through Development: Northeast insurgency incidents declined 70% (2013-2019) with civilian deaths dropping 80%. Suspension of Operations (SoO) accords and economic initiatives reduced violence, demonstrating that targeted development and political dialogue address root causes more effectively than security operations alone. Insurgent fragmentation and declining civilian support reflect gradual improvement in governance and service delivery.

5. Jammu-Kashmir Insurgency: Alienation, Development Deficit, and Radicalization of the Educated

Kashmir’s insurgency represents a distinct pattern: despite relative infrastructural development compared to other insurgency zones, psychological alienation and systematic political exclusion have radicalized educated youth—doctors, engineers, scholars—previously insulated from militancy recruitment.

Development Paradox and Alienation: Kashmir faces among India’s highest unemployment rates despite earlier development investments. The 2016 killing of militant Burhan Wani triggered massive youth mobilization precisely because development had created educated but economically excluded cohorts vulnerable to ideological appeals. Unemployment youth alienation scores (57.59) significantly exceed employed youth (45.27), indicating that economic deprivation alone insufficiently explains radicalization—perceived political exclusion amplifies psychological vulnerability.

Ideological Radicalization Mechanism: Post-1989, foreign jihadist funding replaced Sufi mysticism with Salafi/Wahhabi doctrines, radicalizing educated segments through madrasa networks and encrypted online forums. By the 2000s, educated militants (doctors, engineers) replaced earlier uneducated recruits, driven by ideological conviction and perceived religious duty rather than mere economic desperation.

Governance and Rights Violations: Counterinsurgency operations coupled with repression, militarization, pellet gun deployments, custodial deaths, and bureaucratic denial of basic services intensified grievance. Youth perceive central governance as delegitimized and development promises as hollow. Article 370’s abrogation (2019) further entrenched alienation narratives, with unemployment remaining among India’s highest.

6. Other Regional Insurgencies: Punjabi Separatism and Manipur Ethnic Violence

6.1 Punjab Khalistan Movement: Economic-Ideological Nexus

The Khalistan separatist movement, originating in the 1970s and peaking during 1980-1993, demonstrates how economic grievance—particularly agricultural distress, land inequality, and perceived economic marginalization of Sikhs—intersected with religious-identity politics.

Economic-Identity Intersection: Punjab’s agricultural crisis (late 1970s), declining farm incomes, and unequal wealth distribution created economic grievance among rural Sikhs. Separatist organizations exploited this grievance, positioning Khalistan as solution to perceived Sikh economic marginalization. However, unlike LWE or Northeast insurgencies, Punjab’s relatively higher development levels indicate that development alone cannot prevent ideologically-motivated separatism when coupled with identity-based grievance and external sponsorship.

External Sponsorship Factor: Pakistan’s ISI provided refuge, training, arms, and funding, coordinating Khalistan groups with Islamist terrorists and criminal networks. Criminal organizations “opportunistically aligned” with the movement for legitimacy. This illustrates that development gains can be neutralized when external state actors systematize support for insurgent infrastructure.

Quantified Resolution Through Integrated Approach: Punjab’s insurgency declined substantially post-1993 through combined military operations, police professionalization, development initiatives, and community engagement. Current Khalistan resurgence (2020s) reflects international diaspora mobilization rather than mass domestic support, suggesting successful development and governance have reduced the domestic recruitment pool, though overseas radicalization remains a persistent threat.

6.2 Manipur Ethnic Insurgency: Development Deficit and Inter-Community Competition

Manipur’s insurgency differs from ideological movements—it primarily reflects ethnic competition for resources, autonomy, and state patronage among Meitei and tribal communities (particularly Kuki, Naga populations).

Development Disparity and Ethnic Competition: Unequal development distribution across ethnic groups intensified inter-community tensions. State funding through per-capita transfers primarily benefited the leading Meitei ethnic group, marginalizing tribal populations. This structural inequality created perceived relative deprivation among Kuki and tribal communities, fueling demands for autonomy, separate administrative structures, and resource control. Multiple insurgent groups (PLA, UNLF, NSCN factions) weaponized these grievances.

Casualty Escalation in Underdeveloped Context: May 2023 onwards, ethnic clashes between Kuki and Meitei communities escalated dramatically. By 2024 (April), 27 out of 29 Northeast fatalities occurred in Manipur alone. Since May 2023 outbreak, 186 insurgency-linked deaths (94 civilians, 19 security personnel, 72 insurgents) were recorded. This localized violence demonstrates how development failures, combined with administrative mismanagement and inter-ethnic resource competition, can trigger explosive communal violence despite being geographically limited to one state.

Recruitment in Poverty Context: Insurgent groups in Manipur and broader Northeast collectively budget approximately Rs. 3,600 crore annually—substantial resources enabling recruitment of youth lacking legitimate economic opportunities. Multiple groups (PLA, UNLF, NSCN variants) operate parallel “administrations” providing welfare services that substitute for absent state development, deepening youth organizational allegiance.

7. Linkages Between Development and Extremism: Analytical Framework

7.1 Causal Mechanisms

Horizontal Inequality and Relative Deprivation: Violent extremism emerges not from absolute poverty alone but from horizontal inequalities—systematic disparities between ethnic, regional, or religious groups. UNDP research identifies growing horizontal inequalities as “consistently cited drivers of violent extremism.” When specific groups perceive themselves systematically disadvantaged relative to others in resource access, development opportunities, and governance representation, radical movements become more likely to erupt and achieve mass mobilization.

State Capacity Failure and Non-State Actor Substitution: State failure to provide basic rights, services, and security creates vacuums that non-state actors fill, establishing parallel governance structures. LWE organizations provide land redistribution, wage enforcement, and dispute resolution. Northeast insurgents operate welfare services and “taxation” systems in ungoverned territories. Kashmir militant networks offer identity validation and purpose to alienated youth. These non-state substitutions entrench insurgent legitimacy and deepen community dependence.

Grievance Accumulation: Multiple deprivations—economic exclusion, political marginalization, perceived injustice, human rights violations, corruption, denial of autonomy—collectively create radicalization environments far more effectively than single factors. When “all these horizontal inequalities come together for a particular group,” radical movements become normalized within community discourse.

7.2 Development as Counter-Extremism Strategy

Quantified Evidence: Government statistics demonstrate development’s counter-extremism efficacy:

- LWE Violence Reduction: 81% decrease in incidents (1,936 to 374) from 2010-2024 correlates directly with integrated security-development operations.

- Northeast Incident Reduction: 70% decrease in violent incidents (2013-2019) through Suspension of Operations, economic initiatives, and governance improvements.

- Naxalite Surrenders: Over 8,000 insurgents have abandoned violence in 10 years, coinciding with welfare scheme expansion and livelihood programs targeting tribal communities.

- Affected District Compression: Reduction of most-affected LWE districts from 12 to 6 reflects concentrated development focus in core conflict zones (Chhattisgarh’s Bijapur, Sukma, Kanker; Jharkhand’s West Singhbhum; Maharashtra’s Gadchiroli).

Integrated Security-Development Model: Successful counter-insurgency increasingly combines military operations with welfare expansion, livelihood schemes, political inclusion, and local governance empowerment. India’s “Whole-of-Government Coordination” approach pairs security operations with development initiatives—notably in Kashmir (post-2019) and LWE zones (Integrated Action Plan).

7.3 Limitations and Complexities

Not All Poverty Drives Terrorism: Research consensus indicates poverty alone does not predict terrorist participation. Educated, middle-class recruits appear in wealthy countries. However, weak and failed states—many poorest countries—face heightened terrorist harboring risk, suggesting that state capacity failure combined with poverty creates more dangerous conditions than poverty in functionally governed societies.

Ideological Extremism Transcends Development: Khalistan’s resurgence among diaspora elites and Kashmir’s radicalization of educated youth demonstrate that ideological conviction, religious fervor, and identity politics can mobilize individuals irrespective of personal economic circumstance. Development gains cannot neutralize externally-sponsored ideological movements or diaspora-driven separatism without concurrent political legitimacy and inclusion strategies.

External Sponsorship Amplifies Domestic Grievance: Pakistan’s systematic support for Kashmir and Punjab insurgencies, China’s support for Northeast groups, and Gulf funding for ideological indoctrination show that international geopolitics can weaponize domestic grievances, making development alone insufficient for resolution.

8. Policy Implications: Integrated Counter-Extremism Framework

8.1 Development Priorities

- Targeted HDI Enhancement in Conflict Zones: Priority investment in LWE-affected districts (Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, Odisha) and Northeast states to achieve convergence with national development averages. Current development indices in these regions match African underdeveloped nations—urgent acceleration required.

- Tribal Empowerment and Land Rights: Implement long-delayed constitutional provisions for tribal autonomy, forest rights, and resource management. Land redistribution to landless laborers, enforcement of land ceiling laws, and tribal participation in mining/industrial project decisions address core Naxalite grievances.

- Youth Employment and Skill Development: Establish livelihood programs targeting educated unemployed youth (particularly in Kashmir, Northeast) to prevent radicalization. Economic inclusion of educated cohorts particularly critical given recruitment of doctors, engineers into militant ranks.

- Equitable Resource Distribution: Address horizontal inequalities through development that reaches last-mile beneficiaries. Welfare scheme implementation must reach poorest segments rather than benefiting leading ethnic/regional groups—this reduces relative deprivation perceptions.

8.2 Governance and Security Integration

- Decentralized Governance: Political inclusion through local governance empowerment (particularly autonomy arrangements in Northeast, Kashmir) reduces alienation and insurgent legitimacy claims.

- Judicial Reform and Rights Protection: Eliminate custodial violence, extrajudicial killings, and human rights violations that intensify grievance. Establish accountability mechanisms for security force excesses.

- Intelligence-Development Coordination: Data fusion centers tracking radicalization patterns, particularly online extremism, must coordinate with development agencies to identify vulnerable populations for proactive engagement rather than reactive securitization.

- De-escalation and Negotiation: Suspension of Operations accords, peace processes (particularly with Northeast groups), and dialogue-based conflict resolution demonstrate development efficacy when coupled with political will.

9. Conclusion

The linkage between development and extremism in India is neither coincidental nor tangential—it represents a structural relationship where systematic marginalization, relative deprivation, and state capacity failure create ideological and practical recruitment environments that insurgent organizations systematically exploit.

India’s experience across multiple insurgency contexts—LWE’s tribal targeting, Northeast’s ethnic mobilization, Kashmir’s ideological radicalization, and Punjab’s separatism—demonstrates consistent patterns: underdeveloped regions with poor governance, horizontal inequality, and limited legitimate opportunity become extremism breeding grounds. Conversely, quantified evidence shows that integrated security-development strategies achieve substantial violence reduction.

However, development alone proves insufficient when coupled with ideological conviction, external state sponsorship, or identity-based grievance transcending economic calculation. Comprehensive counter-extremism requires simultaneous pursuit of: targeted development addressing horizontal inequality; governance improvements ensuring political inclusion and institutional legitimacy; judicial reform eliminating rights violations; and security operations containing immediate threats. This integrated framework recognizes that sustainable extremism suppression requires addressing not merely violent manifestations but the underlying structural conditions enabling radicalization processes.

UNDP (2017). “Preventing Violent Extremism: Practice, Promise, and Persistence”

South Asia Terrorism Portal (2024-2025). “Maoist Insurgency and Northeast Insurgency Assessments”

Brookings Institution (2010). “Poverty, Development, and Violent Extremism in Weak States“

Discover more from Simplified UPSC

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.