Public Distribution System- objectives, functioning, limitations, revamping

Contents

Public Distribution System (PDS): Objectives, Functioning, Limitations, and Revamping

The Public Distribution System is India’s largest food security network, serving as a critical instrument of socialist democracy by guaranteeing the right to food as a legal entitlement. Covering over 80.67 crore beneficiaries, the PDS has evolved from a welfare-based colonial mechanism into a rights-based constitutional framework, fundamentally transforming how India addresses hunger and malnutrition among vulnerable populations.

What is the Public Distribution System?

The Public Distribution System is a centrally-sponsored food security scheme implemented jointly by the central government and state governments to distribute essential food commodities at heavily subsidized rates to economically weaker sections of society. The system was formally established after World War II to increase domestic agricultural production and ensure food security, and has now become one of the world’s largest food distribution networks.

As of 2024-25, the PDS caters to approximately 80.67 crore persons against an intended coverage of 81.35 crore persons, with details of nearly 20.54 crore ration cards maintained across all states and union territories through digitized databases.

Constitutional Basis and Socialist Democracy

The PDS represents India’s commitment to socialist democracy as enshrined in the Constitution. The Preamble of the Indian Constitution explicitly mentions the commitment to establishing a socialist order, and this principle finds operational expression through various provisions:

Article 39(a) of the Directive Principles of State Policy mandates: “The State shall direct its policy towards securing that the citizen, men and women equally, have the right to an adequate means of livelihood.” Food security is fundamental to ensuring an adequate means of livelihood. Article 47 further declares: “The State shall regard the raising of the level of nutrition and the standard of living of its people and the improvement of public health as among its primary duties.”

The landmark judgment in PUCL vs. Union of India (2001) transformed the right to food from a mere aspirational principle into a constitutionally enforceable fundamental right by reading it into Article 21 (Right to Life). This judicial interpretation established that the state has a constitutional obligation to ensure no citizen dies from starvation or malnutrition. The National Food Security Act (NFSA), 2013 crystallized this commitment by converting food access into a legal entitlement for two-thirds of India’s population, marking a paradigm shift from welfare to rights-based governance.

Objectives of the Public Distribution System

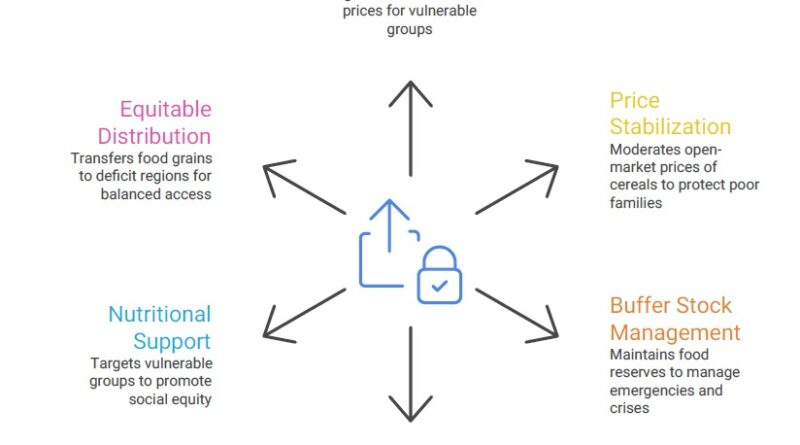

The PDS operates with multiple interlinked objectives aimed at comprehensive food and nutritional security:

Ensuring Food Security for Vulnerable Groups – The primary objective is to provide essential food grains at subsidized prices to protect low-income households from hunger and malnutrition. The system guarantees minimum quantities of food grains at affordable prices to prevent food deprivation.

Price Stabilization – By maintaining substantial buffer stocks and distributing subsidized grains, the PDS exerts a moderating influence on open-market prices of cereals. This shields poor families from inflation and market volatility, particularly during supply shortages or crisis periods.

Buffer Stock Management – The system maintains national-level food reserves to manage emergencies including droughts, floods, natural disasters, and production shortfalls. This reserve capacity ensured the distribution of additional food grains during the COVID-19 pandemic under the Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Anna Yojana, reaching 800 million people.

Support to Agricultural Producers – By procuring food grains at Minimum Support Prices (MSP), the PDS ensures stable and remunerative income for farmers, encouraging sustained agricultural production.

Nutritional Support and Social Equity – The PDS targets particularly vulnerable groups including children, pregnant women, lactating mothers, and economically weaker sections, promoting social equity and reducing regional imbalances in food availability.

Equitable Regional Distribution – Food grains are transferred from surplus states to deficit regions, ensuring balanced access across the country and preventing regional disparities.

Functioning and Structure of the PDS

The PDS operates through an integrated supply chain involving multiple stakeholders and stages:

Procurement Phase – The Food Corporation of India (FCI), a government-owned enterprise under the Ministry of Consumer Affairs, procures food grains from farmers at guaranteed Minimum Support Prices. This procurement occurs primarily after the harvest season and covers rice, wheat, and coarse grains.

Storage and Buffer Management – Procured grains are stored in FCI warehouses and state depots to ensure year-round availability. The system maintains strategic buffer stocks to manage seasonal fluctuations and emergency requirements.

Allocation to States – The central government allocates food grains to states based on multiple criteria including population size, poverty levels, and state-specific requirements. This allocation ensures that deficit states receive adequate supplies while surplus states can contribute to national reserves.

Distribution through Fair Price Shops (FPS) – The backbone of retail distribution consists of approximately 505,879 Fair Price Shops across India, operated at the grassroots level by state governments, private retailers, or cooperative societies. These shops distribute subsidized food grains to cardholders on specified dates monthly.

Beneficiary Identification and Ration Cards – State governments identify eligible beneficiaries based on economic status and issue ration cards that serve as both identification and entitlement documents. The NFSA recognizes two main categories of beneficiaries:

Antyodaya Anna Yojana (AAY): Covers the poorest of the poor, with each household receiving 35 kg of food grains monthly at highly subsidized rates.

Priority Households (PHH): Each member receives 5 kg of food grains monthly including rice at ₹3/kg, wheat at ₹2/kg, and coarse grains at ₹1/kg.

The NFSA covers up to 75% of rural population and up to 50% of urban population, totaling approximately two-thirds of India’s population.

Biometric Authentication and Digital Integration – Under the One Nation One Ration Card (ONORC) scheme, beneficiaries’ Aadhaar numbers are linked to ration cards for biometric authentication. Transactions are processed through electronic Point of Sale (e-PoS) devices at Fair Price Shops, with over 97% of transactions recorded biometrically or Aadhaar-authenticated as of 2024.

Key Features Under NFSA and ONORC

National Portability – The ONORC scheme, rolled out across all 36 States/UTs covering nearly 100% of NFSA beneficiaries, allows migrating beneficiaries to access their entitled food grains from any Fair Price Shop across the country. This is particularly significant for migrant workers, tribals, and informal sector laborers who face geographic mobility.

Integrated Support for Life-Cycle Approach – Beyond the PDS, the NFSA mandates complementary schemes including:

Mid-Day Meal Scheme (MDMS): Free nutritious meals to children aged 6-14 years in government schools

Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS): Free meals and nutritional support to pregnant women, lactating mothers, and children up to 6 years

Maternity Entitlements: ₹6,000 maternity benefit to pregnant women and lactating mothers

Limitations and Challenges of the PDS

Despite its expansive reach, the PDS faces significant systemic challenges that diminish its effectiveness:

Substantial Leakages and Diversions – Approximately 28% leakage occurs in the PDS, resulting in an estimated ₹69,108 crore annual loss according to 2022-23 Household Consumption Expenditure Survey data. Nearly one-third of grains lifted from FCI fail to reach Fair Price Shops, with grains diverted during transportation or sold illegally in open markets.

Targeting Errors – The TPDS suffers from both inclusion and exclusion errors:

Inclusion errors: Non-poor households obtain ration cards despite not qualifying economically

Exclusion errors: Deserving poor households remain outside the system, with exclusion rates having declined from 55% (2004-05) to 41% (2011-12)

Examples include migrant laborers and informal workers struggling to obtain ration cards, while some urban middle-income families access subsidized food.

Supply Chain Inefficiencies – Problems persist in storage, transportation, and inter-agency coordination, causing delays and wastage. Inadequate warehouse capacity leads to spoilage of food grains, particularly in remote, tribal, and hilly regions that frequently experience delayed deliveries and periodic stock-outs.

Census-Based Exclusion – Current beneficiary identification relies on the 2011 Census data, despite India’s population growing to approximately 140 crore by 2024. This creates a gap of potentially 15% more eligible beneficiaries (approximately 13 crore persons).

Biometric Authentication Failures – Many individuals lose access to entitled rations due to Aadhaar-based biometric mismatches during verification, causing wrongful exclusion from beneficiary rolls.

Urban Bias – The PDS functions more efficiently in urban areas with better infrastructure and monitoring, while rural, tribal, and remote regions experience irregular supply and weaker administrative oversight. For example, urban ration shops in metros receive regular stock while tribal districts face transport bottlenecks.

Crop Monoculture and Nutritional Limitations – MSP-driven procurement focuses heavily on rice and wheat, discouraging crop diversification and limiting nutritional variety. This impacts long-term health outcomes and soil sustainability.

Fiscal Strain – The PDS involves substantial subsidy burdens, with over ₹8,700 crore released to states in 2023-24. Budget allocation for 2025 stands at ₹2.03 lakh crore, creating fiscal pressures for state governments.

Poor Quality and Corruption at Fair Price Shops – Issues include under-weighing of food grains, selling poor-quality commodities, charging prices higher than prescribed rates, and manipulation by shop owners and corrupt officials.

Revamping Initiatives and Modernization

Recognizing these challenges, the Government of India has launched comprehensive modernization initiatives to enhance transparency, efficiency, and coverage:

End-to-End Computerization and Digital Supply Chain – The entire supply chain from FCI procurement centers to state depots and ultimately Fair Price Shops is now tracked digitally, significantly reducing diversion and leakage.

GPS Tracking of Transport Vehicles – Truck movements are monitored via GPS to prevent route diversions, delays, or pilferage during grain transportation.

Smart Ration Cards and Biometric Authentication – Secure electronic ration cards with embedded biometrics prevent counterfeiting and ghost beneficiaries, while biometric Point-of-Sale machines authenticate beneficiaries at shop-level transactions.

SMS-Based Monitoring System – Beneficiaries receive real-time SMS alerts when grains are dispatched from depots or arrive at Fair Price Shops, enabling public oversight and reducing corruption.

Bhandaran 360 Platform – Launched in November 2025, this cloud-based ERP platform built on SAP S/4HANA integrates 41 modules across the Central Warehousing Corporation (CWC), covering HR, finance, warehouse management, contract management, and project monitoring. The system links with 35 external systems including ICEGATE and port systems, modernizing warehousing operations.

Anna Darpan Cloud Platform – The FCI’s integrated grain operations platform enables real-time monitoring of storage, movement, and distribution, improving supply chain visibility.

ASHA (Anna Sahayata Holistic AI Solution) – Launched in partnership with the Wadhwani Foundation and backed by the India AI Mission via Bhashini’s multilingual infrastructure, this AI-based platform allows beneficiaries to provide real-time feedback on ration distribution through automated calls in their preferred languages. ASHA reaches 20 lakh beneficiaries monthly across India, substantially improving accountability.

Expansion of Food Basket – Several states including Tamil Nadu and Kerala have introduced diversified food baskets that include pulses, edible oils, iodised salt, and fortified foods through PDS, enhancing nutritional security and reducing dependence on rice and wheat alone.

Universal PDS Models – States like Tamil Nadu and Kerala provide subsidized food grains to all households (universal coverage) rather than targeted distribution, minimizing targeting errors and ensuring comprehensive coverage.

Direct Benefit Transfer (DBT) Pilots – Cautious pilots of direct cash transfer of food subsidies to beneficiary bank accounts have been implemented in select regions to reduce storage and transport-related leakages.

One Nation One Ration Card (ONORC) Expansion – Starting from just 4 states in August 2019, ONORC has been extended to all 36 States/UTs as of 2024, achieving 100% NFSA population coverage. This enables inter-state and intra-state portability, benefiting millions of migrant workers. In Maharashtra alone, approximately 521,696 ration card holders from other states have accessed PDS benefits between January 2020 and December 2023.

Social Audits and Community Monitoring – Local communities, Self-Help Groups (SHGs), and NGOs participate in monitoring Fair Price Shop functioning and reporting irregularities to strengthen grassroots accountability.

Online Grievance Redressal Mechanisms – State-level portals and toll-free helplines enable beneficiaries to lodge complaints and track resolutions, with dedicated grievance redressal officers at district levels mandated under NFSA.

Impact and Effectiveness Evidence

Despite operational challenges, research demonstrates significant positive impacts:

Prevention of Stunting – A 2024 peer-reviewed study found that PDS expansions under NFSA prevented approximately 1.8 million cases of childhood stunting among children under five, demonstrating substantial nutritional benefits.

Dietary Diversity and Wage Improvements – The same research, utilizing panel data from eight states spanning three years pre- and post-NFSA implementation, found that when households spent less on staples through PDS subsidies, they redirected savings toward more diverse diets, particularly animal protein, with wage earnings increasing by more than the transfer amount itself.

Crisis Response – During the COVID-19 pandemic, the PDS buffer stocks enabled distribution of 5 kg additional free food grains per person under the Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Anna Yojana, reaching 800 million people and demonstrating the system’s critical role as a safety net during economic shocks.

PDS as an Instrument of Socialist Democracy

The PDS embodies India’s commitment to economic democracy as articulated in Articles 39 and 47 of the Constitution. As noted by influential development economist Jean Drèze, the right to food forms one of the basic economic and social rights essential to achieve ‘economic democracy’ in India.

By converting food security into a legal right rather than discretionary welfare, the NFSA ensures that citizens can seek judicial remedies if entitlements are denied. This represents a paradigm shift from the colonial rationing system → universal welfare scheme → targeted system → legal rights framework.

The Amartya Sen capability approach, referenced in modernization frameworks, emphasizes that food security is not merely about handouts but about expanding real freedoms. Digital PDS reforms increase accessibility of entitlements, enhance dignity through reduced humiliation, improve transparency in distribution, and enable participation through grievance feedback mechanisms—transforming technology into a means of enhancing human capability rather than mere survival.

Suggested Further Reforms and Future Directions

To strengthen the PDS and fulfill its socialist democratic mandate, several reforms warrant consideration:

Updating Census Data for Beneficiary Identification – Given the 2011 Census basis leaves approximately 13 crore eligible persons uncovered, incorporating updated population estimates would enhance inclusion accuracy.

Strengthening Last-Mile Logistics – Modernizing warehouses in remote regions, expanding scientific storage facilities (silos), and improving transportation infrastructure would reduce spoilage and ensure consistent supply in underserved areas.

Combating Biometric Exclusion – Refining Aadhaar-seeding processes and providing alternative authentication mechanisms for marginalized groups would prevent wrongful exclusion.

Nutritional Basket Expansion – Nationwide inclusion of pulses, fortified grains, edible oils, and micronutrient-rich foods would address undernutrition comprehensively rather than relying solely on rice and wheat.

Digitalization and Real-Time Monitoring – Complete implementation of GPS tracking, e-PoS systems, and AI-based feedback mechanisms across all Fair Price Shops would enhance transparency and accountability.

Conclusion

The Public Distribution System represents one of India’s most significant institutional expressions of socialist democracy, operationalizing the constitutional promise that every citizen has a right to adequate food and nutrition. From its post-independence origins as a colonial rationing mechanism to its current rights-based framework under NFSA, the PDS has evolved to serve over 80 crore beneficiaries, preventing millions of cases of hunger, malnutrition, and stunting.

While substantial challenges—including 28% leakages, targeting errors, supply chain inefficiencies, and urban bias—persist, recent modernization initiatives utilizing AI, digital integration, and blockchain-based tracking offer credible pathways to enhance effectiveness. The successful expansion of ONORC to achieve 100% national portability, coupled with emerging platforms like Bhandaran 360 and ASHA, demonstrate institutional commitment to transforming the system into a transparent, efficient, and truly inclusive food security network.

The PDS’s critical role during the COVID-19 pandemic and its demonstrated impact on nutritional outcomes, dietary diversity, and wage improvements underscore its importance as both a safety net and a development instrument. As India progresses toward eliminating hunger and achieving Sustainable Development Goal 2 (Zero Hunger), strengthening the PDS through data-driven reforms, technological innovation, and constitutional commitment remains imperative.

AGRICULTURE AND FOOD PROCESSING

Discover more from Simplified UPSC

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.