The cost of being wrong is less than the cost of doing nothing

Contents

“The Cost of Being Wrong is Less Than the Cost of Doing Nothing”

“Indecision is the thief of opportunity,” a saying that resonates in today’s fast-paced world where the ability to make decisions can determine success or failure. The philosophy that “the cost of being wrong is less than the cost of doing nothing” challenges our natural aversion to risk and encourages a proactive approach to life’s challenges. While mistakes carry consequences, inaction often breeds stagnation, missed opportunities, and irreversible damage. This essay explores the profound truth that action—even imperfect action—serves as a catalyst for growth, learning, and progress across various domains of human endeavor. By examining historical events, scientific breakthroughs, economic patterns, and personal development, we will demonstrate how the willingness to act and potentially err ultimately proves less costly than the paralysis of inaction.

Historical Perspective on Decision-Making

Throughout history, nations and leaders who took decisive action—even at the risk of being wrong—often fared better than those who hesitated in the face of challenges. The British policy of appeasement toward Nazi Germany in the 1930s exemplifies the devastating cost of inaction. Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain’s reluctance to confront Hitler’s aggression allowed Nazi Germany to grow stronger, ultimately making World War II more catastrophic than it might have been with earlier intervention. In contrast, the United States’ bold decision to enter the war, despite isolationist sentiment, proved crucial in turning the tide against fascism.

Similarly, during the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962, President Kennedy faced immense pressure to launch a military strike against Soviet missile installations in Cuba. Instead, he chose a naval blockade combined with diplomatic negotiations—a risky approach that could have failed. However, this calculated action prevented what might have escalated into nuclear war. Had Kennedy chosen inaction, allowing Soviet missiles to become fully operational in Cuba, or chosen overly aggressive action, the consequences could have been catastrophic.

India’s own history demonstrates this principle. When faced with economic crisis in 1991, the government took the bold step of liberalizing the economy despite significant opposition and uncertainty. This decision, though risky at the time, paved the way for unprecedented economic growth. Had India chosen inaction, clinging to failing policies out of fear of change, the country might have faced economic collapse rather than emergence as a global economic power.

These historical examples illustrate that while decisive action carries the risk of being wrong, the consequences of inaction often prove far more severe and long-lasting. As Winston Churchill aptly observed, “I never worry about action, but only inaction.”

Scientific Progress and Experimentation

The realm of science provides compelling evidence that the cost of being wrong is indeed less than the cost of doing nothing. Scientific progress inherently relies on trial and error—a willingness to form hypotheses, test them, and learn from failures. Alexander Fleming’s discovery of penicillin resulted from a “mistake”—a contaminated culture plate that he chose to investigate rather than discard. Had Fleming been paralyzed by the fear of being wrong or criticized, one of medicine’s most transformative discoveries might never have occurred.

Space exploration represents another domain where action despite uncertainty has yielded tremendous benefits. NASA’s Apollo program faced numerous setbacks, including the tragic Apollo 1 fire. Rather than abandoning the mission out of fear, NASA learned from these failures, implemented crucial safety improvements, and ultimately succeeded in landing humans on the moon—an achievement that expanded human knowledge and capabilities immeasurably.

In the field of medicine, clinical trials frequently yield unexpected results. Many successful treatments were discovered when researchers noticed unintended effects of medications being tested for other conditions. Viagra, for instance, was originally developed as a heart medication before researchers noticed its now-famous side effect. Had researchers been unwilling to pursue unexpected findings out of fear of being wrong, countless life-saving and life-improving treatments might never have been developed.

The scientific method itself embraces the possibility of being wrong as essential to progress. As physicist Richard Feynman noted, “We are trying to prove ourselves wrong as quickly as possible, because only in that way can we find progress.” The alternative—inaction due to the fear of error—would have left humanity without the technological and medical advances that define modern life.

Economic Growth and Entrepreneurship

The business world provides stark contrasts between companies that act decisively despite risks and those that remain inactive out of fear of failure. Amazon, initially an online bookstore, took the bold step of expanding into numerous other retail categories and cloud computing services despite skepticism. Jeff Bezos’s willingness to be wrong—and his famous comfort with failure—transformed Amazon into one of the world’s most valuable companies. Similarly, Tesla’s venture into electric vehicles faced immense skepticism, yet its willingness to challenge the automotive status quo has accelerated the transition to sustainable transportation.

Contrast these success stories with companies that failed due to inaction. Kodak, despite inventing the digital camera in 1975, failed to embrace this technology out of fear of cannibalizing its film business. Nokia dominated the mobile phone market but hesitated to fully embrace smartphone technology. In both cases, the cost of inaction far exceeded the potential cost of making wrong strategic decisions, ultimately leading to their decline.

Start-up culture explicitly recognizes this principle with mantras like “fail fast, fail forward.” Venture capitalists understand that many investments will fail, but the returns from successful ventures outweigh these losses. The alternative—never investing out of fear of failure—guarantees zero return and zero progress.

Economic systems themselves demonstrate this principle. Countries that have embraced economic reform and adaptation, despite short-term disruption, have generally achieved greater prosperity than those maintaining failing systems out of fear of change. China’s economic opening, South Korea’s industrial transformation, and India’s liberalization all involved risk and uncertainty, yet yielded tremendous benefits compared to the certain stagnation of maintaining the status quo.

Political Reforms and Governance

Political history is replete with examples where bold reforms, despite their uncertain outcomes, proved less costly than governmental inaction. The abolition of slavery represented a massive economic and social disruption in many countries, yet few would argue that maintaining this institution would have been preferable to the temporary upheaval of its elimination. Similarly, women’s suffrage faced fierce opposition from those who predicted societal collapse, yet the extension of voting rights strengthened rather than weakened democratic systems.

India’s implementation of land reforms, despite significant opposition from entrenched interests, helped address systemic inequality and poverty. The Green Revolution, which faced initial skepticism, transformed Indian agriculture and helped achieve food security. These examples demonstrate that while political reforms carry implementation risks, they often prevent greater long-term societal costs.

Governance systems that prioritize stability at all costs often fail to address emerging challenges until they become crises. The Soviet Union’s reluctance to reform its economic and political systems led to collapse rather than stability. In contrast, countries like Singapore embraced continuous adaptation and reform, allowing them to navigate changing global circumstances successfully.

Democratic systems inherently recognize this principle by instituting regular elections that force periodic reassessment and change. While this sometimes leads to policy mistakes, it prevents the greater error of perpetuating failed approaches indefinitely. As political philosopher Karl Popper argued, the true advantage of democracy lies not in selecting the best leaders but in providing mechanisms to remove ineffective ones without violence—acknowledging that political action, even when imperfect, is preferable to permanent inaction.

Social Movements and Justice

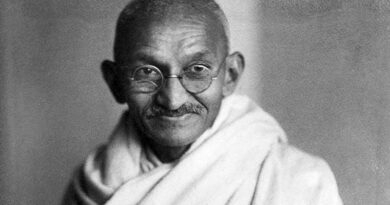

Social progress throughout history has depended on individuals and groups willing to take action despite uncertainty and opposition. The civil rights movement in the United States, led by figures like Martin Luther King Jr., confronted entrenched segregation through direct action rather than waiting for gradual change. While this approach involved risks—including violence against protesters—it catalyzed reforms that might otherwise have taken decades longer.

In India, Dr. B.R. Ambedkar’s advocacy for Dalit rights and against caste discrimination represented a bold challenge to ancient social structures. While his actions and the resulting constitutional protections didn’t immediately eliminate caste prejudice, they established essential legal foundations for equality. The alternative—accepting the status quo out of fear of societal disruption—would have perpetuated injustice indefinitely.

Women’s rights movements worldwide demonstrate similar dynamics. Suffragettes faced ridicule, imprisonment, and violence, yet their willingness to act despite these costs ultimately secured voting rights and began the long process of gender equality. Each step in this journey involved uncertainty and resistance, yet inaction would have maintained systematic discrimination.

Social entrepreneurs and activists constantly face the dilemma of imperfect action versus inaction. Organizations addressing poverty, education gaps, or public health must make decisions with incomplete information. Their programs may sometimes fall short of goals or produce unintended consequences, yet these “mistakes” provide valuable learning that improves future efforts. The alternative—paralysis in the face of complex social problems—guarantees continued suffering for vulnerable populations.

Climate Change and Environmental Policies

Perhaps no contemporary issue better illustrates that the cost of being wrong is less than the cost of doing nothing than climate change. For decades, some argued that climate action should wait for absolute scientific certainty or perfectly designed policies. This inaction has allowed greenhouse gas concentrations to reach levels requiring more drastic and expensive interventions than would have been necessary with earlier action.

Environmental policies always involve trade-offs and uncertainties. Early regulations limiting air pollution faced opposition from industries predicting economic disaster, yet these policies delivered health benefits far exceeding their costs. Similarly, the Montreal Protocol restricting ozone-depleting substances represented action amid scientific uncertainty, yet successfully addressed an environmental threat that could have caused global catastrophe.

While environmental interventions sometimes produce unintended consequences, the ecological systems they protect are often irreplaceable once lost. Extinct species cannot be resurrected, and degraded ecosystems may take centuries to recover, if they can recover at all. This irreversibility makes environmental inaction particularly costly compared to the risks of imperfect action.

The precautionary principle in environmental policy captures this dynamic, suggesting that when activities threaten serious harm to human health or the environment, precautionary measures should be taken even if causal relationships aren’t fully established scientifically. This principle recognizes that the cost of being wrong about environmental threats is typically less than the cost of doing nothing until absolute certainty is achieved—by which time irreversible damage may have occurred.

Personal Growth and Decision-Making

At the individual level, the principle that the cost of being wrong is less than the cost of inaction manifests in countless life decisions. Career changes involve uncertainty and the risk of failure, yet those who remain in unfulfilling jobs out of fear often experience greater long-term costs in terms of satisfaction and development. Educational pursuits, relationships, and personal projects all require action despite imperfect information and the possibility of disappointment.

The psychology of decision-making reveals our tendency toward loss aversion—we feel losses more intensely than equivalent gains. This cognitive bias often leads to inaction, as potential mistakes loom larger in our minds than potential benefits. Recognizing this bias allows individuals to make more rational decisions that account for the hidden costs of inaction.

Consider the person who never pursues entrepreneurship out of fear of failure. While they avoid the potential loss of a failed business, they also forfeit the experience, skills, and potential success that might have resulted. Similarly, those who avoid social situations out of fear of rejection miss countless connections and opportunities that outweigh the temporary discomfort of occasional social missteps.

Learning itself requires a willingness to be wrong. Students who fear asking questions or making mistakes limit their educational development. In contrast, those who embrace a growth mindset—viewing challenges and even failures as opportunities for development—typically achieve greater long-term success. As educational theorist John Dewey observed, “Failure is instructive. The person who really thinks learns quite as much from his failures as from his successes.”

Conclusion

Throughout this exploration of history, science, business, politics, social movements, environmental policy, and personal development, a consistent truth emerges: the cost of being wrong is indeed less than the cost of doing nothing. Mistakes, while sometimes painful and costly, provide opportunities for learning, adaptation, and growth. Inaction, by contrast, often leads to stagnation, missed opportunities, and problems that grow more intractable over time.

This is not to advocate recklessness or disregard for careful analysis. Rather, it suggests that after reasonable consideration, action—even with its inherent risks—typically proves more beneficial than paralysis. As Theodore Roosevelt eloquently stated, “In any moment of decision, the best thing you can do is the right thing, the next best thing is the wrong thing, and the worst thing you can do is nothing.”

The wisdom in this perspective lies in recognizing that errors can be corrected and approaches refined, but time and opportunities lost to inaction can rarely be recovered. Progress in every domain of human endeavor—from scientific discovery to social justice—has depended on individuals and groups willing to act despite uncertainty, learning from inevitable mistakes rather than being immobilized by the fear of them.

As we face personal decisions and collective challenges, we would do well to remember that the path to growth and improvement is paved not with perfect decisions, but with the willingness to act, learn, and adapt. In embracing this truth, we discover that the greatest risk is not in being wrong, but in doing nothing at all.

Discover more from Simplified UPSC

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.