Conquest of Bengal

Contents

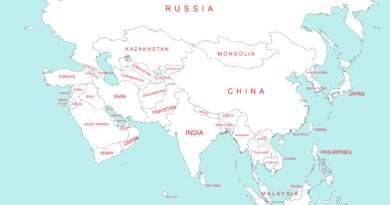

The Conquest of Bengal by the British

The British conquest of Bengal marked a watershed moment in Indian history, transforming the East India Company from a trading entity into a territorial power. This conquest occurred through decisive military victories and strategic administrative arrangements between 1757 and 1765, establishing the foundation for British colonial rule in India.

Background to the Conquest

The East India Company’s growing commercial activities in Bengal increasingly conflicted with the interests of the local Nawab. Several factors precipitated the confrontation between Siraj-ud-Daulah, the last independent Nawab of Bengal, and the British:

Growing British Power: The British victory in the Carnatic wars had already alarmed Siraj-ud-Daulah about the expanding power of the East India Company. He viewed their increasing influence as a direct threat to his sovereignty.

Trade Privileges Misuse: Officials of the Company made rampant misuse of their trade privileges, particularly the dastak system (duty-free trade permits), which adversely affected the Nawab’s finances.

Fortification Without Permission: The British fortified Calcutta without the Nawab’s permission, which he considered a direct challenge to his sovereign authority.

Political Asylum: The Company granted asylum to Krishna Das, son of Raj Ballabh, a political fugitive who had fled with immense treasures against the Nawab’s wishes, further exacerbating tensions.

The Black Hole Tragedy (1756)

In June 1756, an infuriated Siraj-ud-Daulah marched to Calcutta and occupied Fort William. Following the fort’s capture on June 20, 1756, British prisoners were allegedly confined in a small dungeon known as the Black Hole. According to John Zephaniah Holwell, a survivor, 146 people were imprisoned in a room measuring 18 feet by 14 feet with only two small windows. He claimed that 123 prisoners died due to suffocation and heat, though later historical analysis suggests the numbers may have been exaggerated—possibly 64 imprisoned with 21 survivors. Regardless of the exact figures, this incident intensified British determination to reclaim Calcutta and seek retribution.

Battle of Plassey (1757)

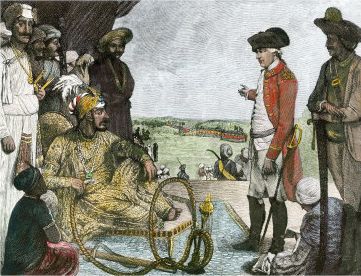

The Battle of Plassey, fought on June 23, 1757, became the decisive turning point in the British conquest of Bengal.

British Forces and Leadership: Robert Clive led approximately 3,000 British and sepoy troops against Siraj-ud-Daulah’s forces of about 18,000 soldiers, which included French allies.

The Betrayal: The battle’s outcome was determined less by military prowess and more by political conspiracy. Clive had bribed Mir Jafar, the commander-in-chief of the Nawab’s army, promising to install him as Nawab in exchange for his betrayal. Other conspirators included the Jagat Seths (powerful bankers), Manik Chand, Aminchand, and Khadim Khan.

The Battle: Despite being significantly outnumbered, the British secured victory in less than eight hours due to Mir Jafar’s refusal to engage his forces. The battle was relatively bloodless from the British perspective, as the betrayal had effectively neutralized the Nawab’s military advantage.

Aftermath: Following the defeat, Siraj-ud-Daulah was captured and executed by Mir Jafar’s son, Miran. Mir Jafar was installed as the puppet Nawab of Bengal. The British extracted enormous compensation—Rs. 17.7 million for the attack on Calcutta, plus substantial personal bribes to Company officials. Robert Clive himself received over two million rupees.

The Puppet Nawabs

Mir Jafar (1757-1760, 1763-1765): Mir Jafar quickly realized that the Company’s demands were boundless. He attempted to break free from British control by secretly allying with the Dutch East India Company. However, the British defeated the Dutch at the Battle of Chinsurah in November 1759 and retaliated by forcing Mir Jafar to abdicate in favor of his son-in-law, Mir Qasim, in October 1760.

Mir Qasim (1760-1763): Mir Qasim proved to be both able and independent-minded. In his first act, he ceded Chittagong, Burdwan, and Midnapore to the East India Company. However, his attempts to assert independence soon raised British suspicions. He relocated his capital from Murshidabad to Munger in Bihar and raised an independent army with European officers. The immediate cause of conflict was Mir Qasim’s opposition to the abuse of dastaks by Company servants for private trade. He formed a powerful alliance with Shuja-ud-Daula (Nawab of Awadh) and Mughal Emperor Shah Alam II to resist British expansion.

Battle of Buxar (1764)

The Battle of Buxar, fought on October 22, 1764, was even more decisive than Plassey.

The Alliance: The combined forces of Mir Qasim, Shuja-ud-Daula, and Shah Alam II numbered between 40,000 to 60,000 troops. This alliance represented the last real chance of resisting British expansion across northern India.

British Victory: Major Hector Munro commanded approximately 7,000 British forces. The battle was closely contested with heavy casualties on both sides, but superior British military discipline and tactics secured victory. The British forces, consisting mainly of Indian sepoys and cavalry, employed superior musket volleys and tactical maneuvering to encircle and defeat the larger Indian force.

Significance: This victory firmly established the British as masters of Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa, and placed Awadh at their mercy. Mir Jafar was reinstalled as Nawab by the British in 1764, holding the position until his death in 1765.

Treaty of Allahabad (1765)

Following the British victory at Buxar, Robert Clive negotiated two separate treaties at Allahabad in August 1765:

Treaty with Shah Alam II (Mughal Emperor):

The Emperor granted the British East India Company Diwani rights—the authority to collect revenue from Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa

The Company agreed to pay an annual tribute of Rs. 26 lakh to the Emperor

The Emperor was granted the districts of Kora and Allahabad and would reside at Allahabad under Company protection

The Company received Rs. 53 lakh for performing Nizamat functions (military defense, police, and administration of justice)

Treaty with Shuja-ud-Daula (Nawab of Awadh):

Awadh was restored to Shuja-ud-Daula with a subsidiary force and guarantee of defense

The Nawab paid Rs. 50 lakh as war indemnity

Allahabad and Kora districts were ceded to Shah Alam II

The frontier was drawn at the boundary of Bihar

Impact: The Treaty of Allahabad marked the political and constitutional involvement of the British in India. It transformed the Company from a trading enterprise into a political and administrative power. The treaty effectively legitimized British control over Bengal through the Mughal Emperor’s grant, while Clive preserved Awadh as a buffer state.

Administrative Changes After the Conquest

Dual Government System (1765-1772)

Robert Clive established the infamous Dual System of Government following the Treaty of Allahabad.

Structure of Dual Government:

Diwani (revenue collection rights): Granted by the Mughal Emperor Shah Alam II, exercised by the Company

Nizamat (police and judicial functions): Retained by the Nawab of Bengal, but controlled through the Company’s right to appoint the deputy subahdar

The Company collected revenues as the Diwan, while the Nawab handled criminal, civil, and police administration for a fixed payment

Characteristics of the System:

Authority was completely divorced from responsibility

The Company enjoyed power without accountability for governance

The Nawab held responsibility for administration without adequate financial resources

Indian officials appointed by the Company collected revenue, leading to widespread corruption and oppression

Consequences of Dual Government:

Administrative Chaos: Neither the Company nor the Nawab took responsibility for efficient governance. The system created confusion and lack of accountability.

Rampant Corruption: Company servants made full use of private trading privileges to enrich themselves through corrupt practices.

Peasant Exploitation: Excessive revenue collection and oppression of the peasantry became widespread. Greedy collectors used harsh measures, forcing those unable to pay to abandon their villages.

Economic Devastation: The Bengal Famine of 1770, which affected approximately 30 million people (one-third of the population), killed between 1-10 million people. The famine resulted from crop failures in 1768-1769, but was severely worsened by the Company’s policies—they provided little relief, did not reduce taxes, purchased large quantities of rice for their army, and created local grain monopolies through their servants. The lack of administrative accountability under the dual system prevented effective famine relief measures.

Neglect of Public Welfare: Both the Company and Nawab remained indifferent to people’s welfare, focusing only on revenue extraction.

Abolition: Recognizing the system’s failures, Warren Hastings abolished the Dual Government in 1772, establishing direct British administrative control over Bengal.

Warren Hastings’ Reforms (1772-1785)

Warren Hastings, appointed first as Governor of Bengal (1772-1774) and then as Governor-General of Bengal (1774-1785) under the Regulating Act of 1773, introduced comprehensive administrative reforms.

Administrative Reforms:

Abolition of Dual System (1772): Hastings ended the dual administration, bringing both revenue and administrative powers under direct British control.

Board of Revenue: Established at Calcutta in 1772 to centralize revenue management and enhance efficiency.

District Administration: Bengal was divided into districts, each headed by a British Collector responsible for revenue collection. An Accountant General was also appointed.

Capital Shift: The treasury and administrative capital were moved from Murshidabad to Calcutta, making Calcutta the effective capital of Bengal in 1772.

Removal of Deputy Subedars: These positions were eliminated to establish direct British administrative control.

Judicial Reforms:

Abolition of Zamindar Courts: Zamindars’ judicial powers were removed.

Civil and Criminal Courts: Separate district courts were established for civil (Diwani Adalat) and criminal (Faujdari Adalat) cases.

Appellate Courts: Two appellate courts were established at Calcutta—Sadar Diwani Adalat for civil cases and Sadar Nizamat Adalat for criminal cases.

Personal Laws: Muslims were tried according to Islamic law (Quran) and Hindus according to Hindu law (Shastras). A code of Hindu law was prepared by Hindu Pandits and translated into English.

Written Proceedings: Judicial proceedings were required to be in writing.

Indian Judges: Indian judges were appointed in criminal courts.

Revenue Reforms:

British Revenue Officers: Appointment of British land revenue officers to ensure better collection and supervision.

Five-Year Settlement: Initially introduced a five-year land revenue settlement (1772), later changed to one-year settlement based on highest bidding through the position of Rai Rayan.

Financial Reforms:

Reduction of Expenses: The Nawab’s pension was reduced from Rs. 32 lakhs to Rs. 16 lakhs.

Stoppage of Tribute: The annual tribute of Rs. 25 lakhs to Shah Alam II was stopped.

Territorial Sales: Districts of Kara and Allahabad were sold to Shuja-ud-Daula for Rs. 30 lakhs.

Currency Improvement: The currency system was reformed and improved.

Trade and Commercial Reforms:

Abolition of Dastaks: The misused system of duty-free passes was abolished.

Uniform Tariff: A uniform tariff of 2.5% was enforced for both Indian and foreign goods.

Restriction on Private Trade: Private trade by Company officials was restricted to reduce corruption.

Abolition of Customs Posts: Large numbers of customs posts were removed to facilitate trade.

Regulating Act of 1773

The British Parliament passed the Regulating Act of 1773 in response to the Company’s misgovernment, bankruptcy, and the threat of financial collapse.

Key Provisions:

Governor-General of Bengal: The Governor of Bengal was redesignated as Governor-General of Bengal. Warren Hastings became the first Governor-General.

Executive Council: A four-member Executive Council was created to assist the Governor-General. Decisions were taken by majority vote, with the Governor-General having a casting vote in case of ties but no veto power.

Centralization of Power: Governors of Madras and Bombay were made subordinate to the Governor-General of Bengal in matters of foreign policy and defense, establishing centralized authority for the first time.

Supreme Court at Calcutta: A Supreme Court of Judicature was established at Fort William in Calcutta in 1774, comprising a Chief Justice (Sir Elijah Impey) and three judges from England. The court had civil and criminal jurisdiction over British subjects but not Indian natives.

Control over Corruption: Company officials were forbidden from engaging in private trade or accepting bribes and gifts from locals.

Parliamentary Oversight: The Company was required to send detailed reports on revenue, civil, and military affairs to the British Government, strengthening parliamentary control.

Financial Regulation: The dividend payable to shareholders was capped at 6% until the Company’s debts were cleared.

Significance:

First intervention by the British Parliament in the Company’s territorial affairs

Marked the beginning of parliamentary control that culminated in the complete takeover of India in 1858

Recognized for the first time the political and administrative functions of the Company

Established the groundwork for centralized administration in India

Defects: The act had several flaws, including the Governor-General’s lack of veto leading to quarrels with councillors, and the Supreme Court’s undefined jurisdiction leading to legal disputes.

Cornwallis Reforms (1786-1793)

Lord Cornwallis, who served as Governor-General from 1786 to 1793, introduced sweeping reforms that further transformed British administration in Bengal.

Permanent Settlement (1793):

The Permanent Settlement, also known as the Zamindari System, was introduced in Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa in 1793.

Background: The idea was first conceived by Philip Francis during Warren Hastings’ regime but was initially rejected. After successive revenue experiments failed, the concept was revived. The Pitt’s India Act (1784) specifically mentioned that land should be settled with zamindars on a permanent basis.

Key Features:

Zamindars were declared absolute proprietors of land with hereditary rights

Land became private property, freely transferable and inheritable according to Hindu and Muslim laws

Government revenue demand was fixed permanently based on the 1790 assessment

Zamindars had to pay 89% of land revenue to the British, retaining only 11%

Land revenue was fixed for perpetuity (initially for ten years, then made permanent)

Farmers were reduced to the status of tenants who could be evicted

Defaulting zamindars’ property could be sold in public auction for recovery of arrears

Impact:

Created an Indian landed class interested in supporting British authority

Provided social and political stability to Bengal

Revenue remained fixed while expenses increased, reducing Company income over time

Neglected rights of lesser landholders and undertenants

Zamindars often failed to provide land deeds (pattas) to farmers

Led to famines as zamindars forced cultivation of cash crops (cotton, indigo, jute) rather than food crops

Failed to generate expected private investment in agricultural infrastructure

Civil Service Reforms:

Anti-Corruption Measures: Strict rules were enforced, including banning private trade and gifts for civil servants.

Merit-Based Appointments: Only qualified persons could enter service, with seniority-based promotions.

Salary Increases: Salaries were raised to reduce bribery and corruption.

Racial Discrimination: Top administrative posts were reserved exclusively for Europeans, while Indians were given only lower positions like clerks and peons.

Father of Indian Civil Service: Cornwallis is regarded as the “father of the Indian civil service” due to these reforms.

Judicial Reforms:

Court System: Established courts at district, provincial, and state levels, with the Supreme Court of Calcutta as the highest court.

Separation of Courts: Created separate courts for civil and criminal cases.

Accountability: Government servants could be sued by people for their mistakes.

Abolition of Torture: Banned torturous punishments like chopping off limbs, nose, and ears.

Court Fees: Abolished court fees, with lawyers prescribing their own fees.

Police Reforms:

Centralized Control: Transferred police control from zamindars to the District Superintendent of Police.

Thana System: Established thanas (police stations) to maintain law and order.

Anti-Slavery Measures: Proclaimed in 1789 that people practicing slavery would be prosecuted by law.

Cornwallis Code (1793):

The comprehensive set of regulations issued on May 1, 1793, became known as the Cornwallis Code, which provided the administrative framework for British India until the Charter Act of 1833.

Service Division: Company personnel were divided into three branches—revenue, judicial, and commercial.

Compensation: Members of revenue and judicial branches were forbidden from private trade but compensated with generous salaries.

Local Administration: Revenue collectors became district administrators.

Judicial Reorganization: District judges had magisterial powers, responsible to provincial courts in civil cases and courts of circuit in criminal cases.

Law Applied: Hindu and Muslim personal law and modified Muslim criminal code were administered.

European Monopoly: Higher ranks were restricted to Europeans, excluding Indians from responsible office.

The British conquest of Bengal through the battles of Plassey and Buxar, followed by comprehensive administrative reforms, fundamentally altered the political landscape of India. These developments transformed the East India Company from a commercial entity into a sovereign power, laying the foundation for nearly two centuries of British colonial rule. The administrative systems established during this period—from the exploitative Dual Government to the more systematic reforms of Warren Hastings and Cornwallis—shaped the governance structures that would persist throughout the colonial era.

Discover more from Simplified UPSC

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.