Seismic waves

Contents

Seismic waves

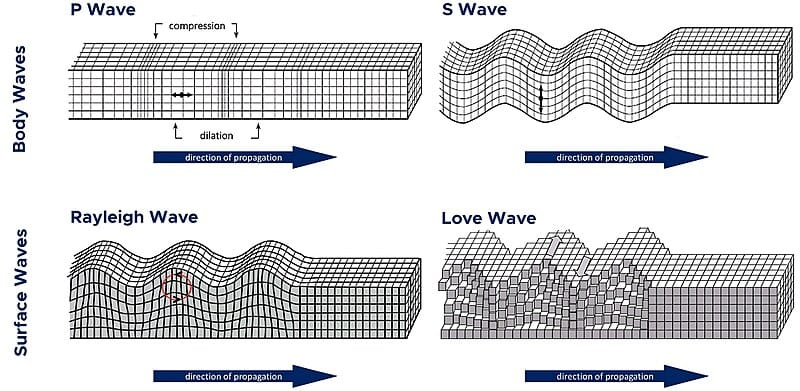

Seismic waves are vibrations that travel through and around the Earth, typically generated by the sudden release of energy during earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, or man-made explosions. These waves serve as our primary window into Earth’s interior, revealing crucial information about its structure, composition, and dynamics that would otherwise be inaccessible. The study of these waves has revolutionized our understanding of our planet, from its crust to its innermost core.

A. Body Waves: Earth’s Internal Messengers

Body waves travel through Earth’s interior rather than along its surface. They are the fastest seismic waves and are the first to be detected following an earthquake. These waves provide critical information about the deep structure of our planet by the way they interact with different materials and boundaries within the Earth.

1. Primary Waves (P-Waves)

Primary waves, commonly known as P-waves, are the fastest traveling seismic waves and thus the first to arrive at seismic stations following an earthquake. These waves derive their name from this “primary” arrival characteristic. P-waves are compressional or longitudinal waves, meaning they cause particles to oscillate in the direction parallel to the wave propagation. This motion creates alternating compression and expansion in the medium through which they travel, similar to sound waves or the movement of a spring when compressed and released1.

One of the most significant properties of P-waves is their ability to travel through all states of matter: solids, liquids, and gases. In air, P-waves travel at approximately 330 meters per second, but their velocity increases dramatically in denser materials, reaching up to 5,000 meters per second in granite1. The speed of P-waves generally increases with depth as they encounter denser materials in the Earth’s interior. This variation in velocity provides valuable information about the composition and density of Earth’s layers.

Despite their high velocity, P-waves typically cause relatively minor damage during earthquakes compared to other seismic wave types. They create a pushing and pulling motion in the ground, causing structures to expand and contract horizontally. P-waves have the highest frequency among seismic waves, but their energy dissipates more quickly than other wave types3. The first sensation experienced during an earthquake is usually the vertical motion caused by P-waves before the more damaging waves arrive.

2. Secondary Waves (S-Waves)

Secondary waves, or S-waves, are the second type of body wave to arrive at seismic stations following an earthquake, arriving after P-waves. S-waves are transverse or shear waves, meaning they cause particles to move perpendicular to the direction of wave propagation. This perpendicular motion creates a shearing effect in the material they travel through, similar to how a rope moves when one end is jerked up and down.

A crucial characteristic of S-waves is their inability to propagate through fluids. Unlike P-waves, S-waves can only travel through solid materials because liquids and gases cannot support the shear stress necessary for transverse wave propagation. This property has profound implications for understanding Earth’s interior, particularly in identifying liquid regions such as the outer core.

S-waves travel more slowly than P-waves, typically at about 60% of P-wave velocity in the same material. However, despite their slower speed, S-waves are considerably more destructive than P-waves. They create a side-to-side or up-and-down motion perpendicular to their direction of travel, which can cause buildings to sway and potentially collapse. The lower frequency of S-waves compared to P-waves allows them to maintain their energy over longer distances, contributing to their destructive potential.

Body Waves

- Definition: Seismic waves that travel through Earth’s interior.

- Types: Primary waves (P-waves) and Secondary waves (S-waves)

Longitudinal (compressional) waves.

Fastest seismic waves; first to arrive at seismic stations.

Travel through solids, liquids, and gases.

Cause particles to move parallel to wave propagation (push-pull motion).

Higher frequency but less destructive compared to S-waves.

Velocity increases with depth due to denser materials.

Transverse (shear) waves.

Slower than P-waves; arrive second at seismic stations.

Can only travel through solids (cannot propagate through liquids or gases).

Cause particles to move perpendicular to wave propagation (side-to-side or up-and-down motion).

More destructive than P-waves due to greater amplitude and energy retention.

Velocity is about 60% of P-wave velocity in the same medium.

| Characteristic | P-Waves | S-Waves |

|---|---|---|

| Type | Longitudinal (compressional) | Transverse (shear) |

| Speed | Faster | Slower |

| Medium | Solids, Liquids, Gases | Only Solids |

| Arrival | First | Second |

| Damage | Less destructive | More destructive |

| Particle Motion | Parallel to wave direction | Perpendicular to wave direction |

| Frequency | Higher | Lower than P-waves, higher than surface waves |

| Penetration | Can pass through all layers of Earth with refraction | Cannot pass through liquid outer core |

This distinct behavior of P-waves and S-waves, particularly their different velocities and ability to travel through various materials, enables seismologists to identify the boundaries between Earth’s layers and determine their composition and physical state.1

B. Surface Waves

Surface waves travel along the Earth’s surface rather than through its interior. These waves are generally slower than body waves but often cause more damage due to their larger amplitudes and longer durations. Surface waves are typically generated when body waves reach the Earth’s surface and transfer their energy. The two primary types of surface waves are Love waves and Rayleigh waves, each with distinctive motion patterns and properties.

1. Love Waves

Love waves, named after the British mathematician A.E.H. Love who predicted their existence, are a type of surface wave characterized by horizontal motion perpendicular to the direction of wave propagation. These waves cause the ground to move side-to-side in a horizontal plane that is perpendicular to the direction the wave is traveling5. This horizontal shearing motion makes Love waves particularly damaging to structures that are not designed to withstand lateral forces.

Love waves require a velocity gradient to exist – they form in environments where the wave velocity increases with depth. They are essentially trapped S-waves that travel parallel to the Earth’s surface and bounce between the surface and a higher velocity layer below. Love waves can only exist in solid media as they involve shear motion, which fluids cannot support.

Among surface waves, Love waves are generally faster than Rayleigh waves, though both travel more slowly than body waves. The horizontal motion of Love waves can be especially damaging to the foundations of structures and can cause significant ground displacements during major earthquakes. The motion is confined to the surface layers, with amplitude decreasing with depth.

2. Rayleigh Waves

Rayleigh waves, named after Lord Rayleigh who mathematically predicted their existence in 1885, are complex surface waves that combine both longitudinal and transverse motions to create an elliptical rolling motion similar to ocean waves. In Rayleigh waves, particles near the Earth’s surface move in retrograde elliptical paths – counterclockwise when the wave travels from left to right. This rolling motion decreases exponentially with depth below the surface.

One distinctive characteristic of Rayleigh waves is that they can exist at the interface between a solid and a vacuum or fluid, making them ubiquitous in natural environments. They can travel along any free surface, including the boundary between the Earth and the atmosphere. The depth of significant particle motion in Rayleigh waves is approximately equal to their wavelength, meaning longer wavelength Rayleigh waves affect deeper portions of the Earth’s crust.

Rayleigh waves typically travel slightly slower than Love waves in the same medium. Their speed is slightly less than that of S-waves by a factor dependent on the elastic constants of the material. In metals, Rayleigh waves typically travel at speeds of 2-5 kilometers per second, while in near-surface ground materials, their speed ranges from 50-300 meters per second for shallow waves (less than 100m depth) and 1.5-4 kilometers per second at depths greater than 1 kilometer.

A notable property of Rayleigh waves is their slow decay with distance compared to body waves. While body waves spread out in three dimensions from a point source, Rayleigh waves are confined near the surface and their amplitude decays only with the square root of distance. This slower decay allows Rayleigh waves to circle the globe multiple times following major earthquakes and still maintain measurable amplitudes.

In seismology, Rayleigh waves are sometimes referred to as “ground roll” and can be produced not only by earthquakes but also by ocean waves, explosions, railway trains, vehicles, or even a sledgehammer impact. Their rolling motion and relatively high amplitude make them among the most destructive seismic waves during major earthquakes.

Surface Waves

: Seismic waves that travel along Earth’s surface; slower but more destructive than body waves.

: Love waves and Rayleigh waves.

Horizontal motion perpendicular to wave propagation (side-to-side shearing).

Faster than Rayleigh waves among surface waves.

Confined to the Earth’s surface layers.

Cause significant damage to structures due to lateral forces.

Rolling motion combining longitudinal and transverse movements (retrograde elliptical motion).

Slower than Love waves but longer-lasting.

Can travel along solid-fluid interfaces like the Earth’s surface.

Affect deeper layers depending on wavelength; amplitude decreases exponentially with depth.

| Characteristic | Love Waves | Rayleigh Waves |

|---|---|---|

| Particle Motion | Horizontal shear | Elliptical (up & down, side-to-side) |

| Speed | Faster among surface waves | Slightly slower |

| Movement | Side-to-side | Rolling motion |

| Occurrence | Confined to surface | Also near surface |

| Motion Direction | Perpendicular to wave propagation | Complex: both parallel and perpendicular components |

| Decay with Depth | Rapid | Exponential, affecting depth equal to wavelength |

| Medium Requirements | Requires velocity gradient | Can exist at solid-fluid interface |

| Named After | A.E.H. Love | Lord Rayleigh |

Both types of surface waves can exhibit dispersion, where different frequencies travel at different speeds. This dispersive nature causes surface waves to spread out over time and distance, creating the extended shaking felt during earthquakes.

Shadow Zones

Regions where seismic waves are not detected directly due to Earth’s internal structure.

Occurs between 103° and 142° from the earthquake epicenter.

Caused by refraction of P-waves at the mantle-core boundary due to the liquid outer core.

Covers a larger area from 103° to 257° angular distance from the epicenter.

Exists because S-waves cannot propagate through the liquid outer core.

Shadow zones are regions on the Earth’s surface where certain seismic waves do not arrive directly after an earthquake. These zones exist due to the interaction of seismic waves with Earth’s different layers, particularly the core. The existence and characteristics of shadow zones provided some of the first evidence for the layered structure of Earth’s interior and continue to be valuable tools in understanding the composition and properties of these layers.

P-Wave Shadow Zone

The P-wave shadow zone is a region on the Earth’s surface where P-waves are not detected directly following an earthquake. This zone exists between approximately 103° and 142° angular distance from the earthquake epicenter6. The primary reason for this shadow zone is the presence of Earth’s liquid outer core and the behavior of P-waves when they encounter the boundary between the mantle and the outer core.

When P-waves traveling through the mantle encounter the liquid outer core, they experience significant refraction due to the abrupt change in density and elasticity between these layers. This refraction causes the P-waves to bend sharply, creating a region on the surface where no direct P-waves arrive. Although P-waves can travel through liquids, the severe bending at the mantle-core boundary creates this shadow zone6.

However, some P-waves do eventually reach parts of the shadow zone after being refracted through the outer core and back into the mantle. These twice-refracted waves arrive later than direct P-waves would and have different characteristics, allowing seismologists to identify them as waves that have traveled through the core.

S-Wave Shadow Zone

The S-wave shadow zone is considerably larger than the P-wave shadow zone, covering almost half of the Earth’s surface. It begins at approximately 103° from the earthquake epicenter and extends to about 257°, encompassing a total angular distance of 154°6. The existence of this extensive shadow zone is due to a fundamental property of S-waves: they cannot propagate through liquids.

When S-waves reach the boundary between the mantle and the liquid outer core, they cannot continue through the liquid material because liquids have no shear strength and cannot support the transverse motion of S-waves. Instead, some S-wave energy is converted to P-waves that can travel through the liquid outer core, while the rest is reflected back into the mantle. As a result, no direct S-waves are detected beyond approximately 103° from an earthquake’s epicenter.

The S-wave shadow zone provided crucial evidence for the existence of Earth’s liquid outer core. The complete absence of S-waves in this region can only be explained by the presence of a liquid layer that blocks S-wave propagation, contributing significantly to our understanding of Earth’s internal structure.

Importance of Seismic Waves in Understanding Earth’s Interior

Seismic waves are crucial for studying Earth’s structure and dynamics:

Reveal Earth’s layered structure (crust, mantle, core) through wave behavior at boundaries.

Provide information about material properties like density, elasticity, and composition using wave velocities.

Help identify liquid and solid regions within Earth:

S-wave absence indicates a liquid outer core.

P-wave refraction confirms a solid inner core.

Enable seismic tomography for creating 3D images of Earth’s interior, revealing features like mantle plumes and subducting slabs.

Aid in earthquake hazard assessment and engineering for designing earthquake-resistant structures.

Used in resource exploration (oil, gas, minerals) via controlled seismic surveys.

Contribute to global monitoring systems for nuclear test ban treaty verification.

Seismic waves serve as invaluable tools for scientists seeking to understand the Earth’s internal structure, composition, and dynamics. Without the ability to directly observe deep Earth, seismologists rely on how these waves travel through and around our planet to infer its properties. The importance of seismic waves in Earth science research spans multiple dimensions of scientific inquiry and practical applications.

Seismic waves provide the primary means for determining the Earth’s internal layered structure. The way different wave types travel, refract, reflect, and attenuate at various depths allows seismologists to identify major boundaries within the Earth, such as the crust-mantle boundary (Mohorovičić discontinuity), the mantle-outer core boundary, and the outer core-inner core boundary. The precise arrival times of P-waves and S-waves at seismic stations around the world enable the creation of detailed models of Earth’s interior structure.

The behavior of seismic waves reveals physical properties of Earth materials at different depths. The velocity of seismic waves depends on the density and elasticity of the materials they travel through. By measuring wave velocities at different depths, scientists can infer changes in composition, temperature, and pressure throughout the Earth. The inability of S-waves to propagate through the outer core provided crucial evidence that this region is liquid, while their propagation through the inner core indicates its solid state despite extremely high pressures and temperatures.

Seismic tomography, a technique analogous to medical CT scanning, uses seismic wave data to create three-dimensional images of Earth’s interior. This has revealed complex structures such as subducting slabs, mantle plumes, and variations in core-mantle boundary topography. These images help geologists understand mantle convection, plate tectonics, and the thermal evolution of our planet. The detection of regions with anomalously high or low seismic velocities has led to discoveries about compositional heterogeneities within the Earth.

From a practical perspective, understanding seismic wave propagation is essential for earthquake hazard assessment and engineering. Knowledge of how different wave types affect structures helps engineers design buildings and infrastructure that can withstand seismic events. Seismic wave analysis also contributes to early warning systems that can provide critical seconds to minutes of advance notice before damaging waves arrive at populated areas.

Beyond studying natural earthquakes, controlled seismic surveys using artificial sources like explosions or vibrating trucks create smaller seismic waves used in exploration geophysics. These techniques help locate valuable resources like oil, natural gas, groundwater, and mineral deposits by mapping subsurface structures. The petroleum industry, in particular, relies heavily on seismic reflection surveys to identify potential hydrocarbon reservoirs.

The global network of seismographs continuously monitors seismic waves from earthquakes worldwide, contributing to our understanding of global tectonics and Earth dynamics. This network also serves as a verification system for nuclear test ban treaties, as underground nuclear explosions generate distinctive seismic signatures that can be distinguished from natural earthquakes.

Discover more from Simplified UPSC

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.