The Western Chalukyas of Badami c. 543-755 CE

Contents

The Western Chalukyas of Badami

Introduction

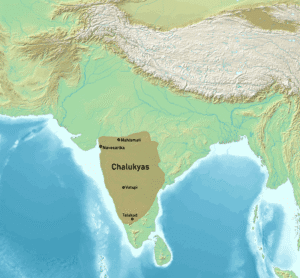

The Western Chalukyas of Badami, also known as the Early Chalukyas or Badami Chalukyas, represent one of the most significant dynasties in medieval Indian history. Ruling from their capital at Vatapi (modern Badami) in Karnataka from 543-755 CE, they established the first major South Indian empire that unified the Deccan plateau and created lasting administrative, cultural, and architectural legacies that influenced subsequent dynasties.

Origins and Rise to Power

The Chalukyas emerged during the decline of the Kadamba kingdom of Banavasi, initially serving as their vassals before asserting independence. The dynasty’s founder, Jayasimha I, was likely a vassal ruler who gradually consolidated power in the region. However, the true architect of Chalukyan sovereignty was Pulakesin I (543-566 CE), who established Badami as his capital by constructing a formidable hill fortress in 543-544 CE. He performed the prestigious Ashvamedha (horse sacrifice) ceremony to assert his sovereign status and adopted the title Vallabheshvara, marking the formal beginning of independent Chalukyan rule.

Major Kings and Their Achievements

Pulakesin I (543-566 CE)

The founder of the dynasty laid the groundwork for Chalukyan expansion by establishing Vatapi as a strategic capital and performing royal ceremonies to legitimize his rule. His choice of the hill-fort location was tactically brilliant, providing natural defenses through surrounding hills and rivers.

Kirtivarman I (566-597 CE)

Son of Pulakesin I, Kirtivarman I significantly expanded the kingdom through systematic military campaigns. He defeated the Kadambas of Banavasi, annexing their capital and breaking up their confederacy. His victories against the Mauryas of Konkana, the Nalas of Nalavadi, and the Alupas extended Chalukyan territory from the Konkan coast to the Shimoga district. The Aihole inscription describes him as “the night of doom” for these enemies, and he was renowned for “fostering justice to his subjects”.

Mangalesha (597-609 CE)

Brother of Kirtivarman I, Mangalesha served initially as regent when Pulakesin II was too young to rule. He continued territorial expansion and consolidated Chalukyan power, establishing control over the region between the two seas and defeating the Kalachuris of Chedi. However, his later attempt to deny the throne to the rightful heir led to civil conflict.

Pulakesin II (609-642 CE) – The Greatest Chalukyan Ruler

Pulakesin II stands as the most illustrious Chalukyan monarch, transforming the kingdom into a vast empire. Born as Ereya, he had to fight his uncle Mangalesha for the throne, ultimately defeating and killing him at modern-day Kolar. His reign marked unprecedented territorial expansion and diplomatic achievements:

Military Conquests:

– Defeated Harshavardhana at the banks of the Narmada River, establishing the river as the boundary between northern and southern India

– Conquered large parts of the Deccan, earning the title Dakshinapatheshvara (Lord of the South)

– Subjugated the Latas, Malavas, and Gurjaras in the north

– Defeated rulers of Dakshina Kosala and Kalinga in the east

– Initially successful against the Pallavas, though later defeated by Narasimhavarman I

Administrative Innovations:

– First South Indian ruler to issue gold coins

– Established his brother Vishnuvardhana as governor of eastern Deccan, founding the Eastern Chalukya dynasty of Vengi

– Maintained a powerful navy with 100 ships

Diplomatic Recognition:

– Exchanged embassies with Persia, indicating international recognition

– Received the Chinese pilgrim Xuanzang at his court

Vikramaditya I (655-680 CE)

After Pulakesin II’s death and a period of Pallava occupation, Vikramaditya I restored Chalukyan power. His major achievement was recapturing Vatapi from the Pallavas and consolidating the fractured empire. He successfully plundered Kanchipuram, the Pallava capital, and restored Chalukyan prestige in the Deccan.

Kirtivarman II (746-753 CE)

The last ruler of the dynasty, Kirtivarman II faced the rising power of the Rashtrakutas under Dantidurga. Continuous warfare with the Pallavas had weakened the empire economically and politically, leading to the assertion of feudatory powers. His defeat in 753 CE marked the end of the Badami Chalukyas and the rise of Rashtrakuta supremacy.

Political System and Administration

Government Structure

The Chalukyas established a hereditary monarchical system with the king as the supreme authority. The ruler held titles such as Paramabhattaraka, Maharajadhiraja, and Parameswara, emphasizing their elevated status.

Central Administration:

– King: Head of administration and highest judicial authority

– Mahamatya: Prime Minister who advised the king

– Council of Ministers (Mantrimandala): Advisory body for governance

Administrative Divisions

The empire was organized into a hierarchical system :

– Maharashtrakas: Provinces

– Rashtrakas (Mandalas): Regional divisions

– Vishayas: Districts headed by Vishayadhipatis

– Bhogas: Groups of ten villages

– Gramas: Individual villages

Military Organization

The Chalukyas maintained a well-organized military system:

– Chaturangini: Four-winged army (infantry, cavalry, elephants, chariots)

– Dandanayaka: Chief military commander

– Mahaprachanda Dandanayaka: Senior military officers

– Samantas: Feudatory rulers maintaining separate armies

Unique Administrative Features

Unlike other South Indian dynasties, the Chalukyas exercised paternalistic control over village administration, reducing local autonomy. This centralized approach differed significantly from the Pallava and Chola systems, which allowed greater village self-governance.

Revenue System

The primary source of income was land revenue, typically assessed at one-sixth of agricultural production. Additional taxes included pilgrimage taxes, trade duties, and various ceremonial levies. The dynasty introduced systematic land grants (agraharas) to Brahmins and temples, supporting religious institutions and scholarship.

Art and Culture

Architecture: The Birth of Vesara Style

The Chalukyas made revolutionary contributions to Indian temple architecture by developing the Vesara style, a synthesis of North Indian Nagara and South Indian Dravidian architectural traditions.

Key Architectural Sites:

Aihole – “Cradle of Hindu Rock Architecture”:

– Contains approximately 125 temples dating from the 6th century

– Served as an experimental center where architects blended different styles

– Notable temples include Durga Temple, Lad Khan Temple, and Ravana Phadi Cave

Badami – Rock-cut Cave Temples:

– Four magnificent cave temples carved directly into sandstone cliffs

– Features three basic elements: pillared veranda, columned hall, and deep-cut sanctum

– Contains intricate sculptures and running friezes of Ganas in various postures

– Bhutanatha Temple Group represents later Chalukyan structural architecture

Pattadakal – UNESCO World Heritage Site:

– Coronation city of Chalukyan kings

– Contains ten 7th-8th century temples showcasing architectural maturity

– Perfect blend of northern and southern styles, with six temples in Dravidian style and four in Nagara style

Architectural Innovations:

– Vesara towers: Modified Dravidian vimanas with reduced height and descending order storeys

– Elaborate mandapas: Halls with domical or square ceilings featuring mythological carvings

– Ornate pillars: Miniature decorative pillars with distinctive artistic value

– Stellar plans: Star-shaped temple layouts

Literature and Learning

The Chalukyan court was a center of literary patronage and scholarly activity:

Sanskrit Literature:

– Ravikirtti, a Jain monk and court poet of Pulakesin II, composed the famous Aihole Inscription (634-635 CE). This eulogy is considered one of the finest examples of Sanskrit epigraphic poetry and provides crucial historical information about Chalukyan achievements.

Vernacular Literature:

– Early development of Kannada literature during this period

– The Kappe Arabhatta record (700 CE) represents the earliest work in Kannada poetics using the tripadi (three-line) meter

– Karnateshwara Katha, a literary work featuring Pulakesin II as the hero

Other Literary Works:

– Saptavataram: A Sanskrit grammar work by a chieftain of Pulakesin II

– Kaumudi Mahotsav: Written by Vijjika, Pulakesin II’s daughter-in-law

– Prabhrita: Authored by Syamakundacharya around 650 CE

Religious Policy and Patronage

The Chalukyas demonstrated remarkable religious tolerance while being primarily Hindu rulers:

Religious Diversity:

– Though Vaishnavite Hindus, Chalukyan rulers patronized Buddhism and Jainism

– Pulakesin II had Jain scholars like Ravikirtti in his court

– Construction of temples for multiple faiths, including Jain sanctuaries

Religious Centers:

– Badami, Aihole, Pattadakal, and Mahakuta emerged as major centers of religious art and architecture

– Groups of mahajanas (learned Brahmins) managed educational institutions called ghatikas

– 2000 mahajanas served at Badami while 500 served at Aihole

Cultural Synthesis

The Chalukyan period witnessed significant cultural synthesis:

– Integration of North and South Indian architectural elements

– Patronage of multiple religious traditions

– Development of distinctive artistic styles in sculpture and painting

– Creation of a cosmopolitan court culture that attracted scholars and artists from various regions

Economic Foundation

Agriculture and Trade

Agriculture formed the backbone of the Chalukyan economy, with sophisticated irrigation systems including tanks, wells, and canals supporting crop production. The dynasty facilitated extensive maritime trade with Persia, Arabia, and Southeast Asia, leveraging their strategic coastal location.

Commercial Organization:

– Powerful merchant guilds (shrenis) like Manigramam and Ayyavole regulated trade and provided financial services

– These guilds contributed to public works projects, including temple construction and water tank development

Decline and Fall

The decline of the Badami Chalukyas resulted from multiple factors:

Continuous Warfare:

The prolonged Chalukya-Pallava conflict drained the empire’s resources and weakened central authority. The rivalry with Narasimhavarman I and subsequent Pallava rulers created constant military pressure on the southern borders.

Rise of Feudatories:

The Rashtrakutas, initially loyal feudatories, gradually increased their power while the Chalukyas were preoccupied with southern campaigns. Dantidurga of the Rashtrakutas took advantage of Chalukyan weakness to establish control over Maharashtra and Gujarat.

Economic Strain:

Continuous military campaigns and territorial losses created economic instability, reducing the empire’s ability to maintain control over distant territories.

Final Defeat:

In 753 CE, Kirtivarman II was defeated and killed by Krishna I, Dantidurga’s successor, marking the end of the Badami Chalukyan dynasty. The empire was subsequently absorbed into the expanding Rashtrakuta kingdom.

Legacy and Historical Significance

The Western Chalukyas of Badami left an indelible mark on Indian civilization:

Political Legacy:

– Established the template for large-scale Deccan empires

– Created administrative systems that influenced later dynasties

– Demonstrated the viability of South Indian imperial power competing with North Indian empires

Cultural Contributions:

– Developed the Vesara architectural style that became the foundation for later Deccan temple architecture

– Fostered religious tolerance and cultural synthesis

– Patronized literature and learning, contributing to the development of regional languages

Architectural Heritage:

The rock-cut and structural temples at Badami, Aihole, and Pattadakal remain UNESCO World Heritage sites, representing some of the earliest and best-preserved examples of evolved Indian temple architecture.

Historical Importance:

The Chalukyan period marked the transition from smaller regional kingdoms to large territorial empires in South India, establishing patterns of governance, culture, and interstate relations that would characterize medieval Deccan politics for centuries.

The Western Chalukyas of Badami thus represent a pivotal chapter in Indian history, bridging the ancient and medieval periods while creating lasting institutions and cultural forms that shaped the subsequent development of South Indian civilization.

Source: Maharashtra Gazetteers

also read: Early Medieval India

Discover more from Simplified UPSC

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.