THE WESTERN GANGAS OF MYSORE

Contents

THE WESTERN GANGAS OF MYSORE

INTRODUCTION

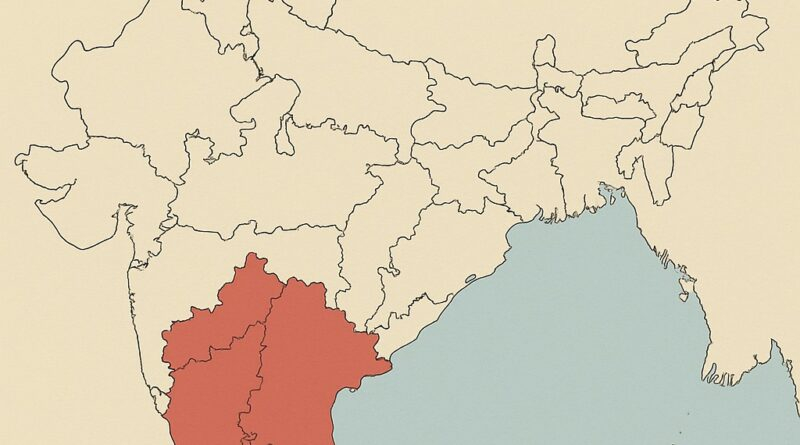

The Western Ganga Dynasty stands as one of the most significant indigenous ruling powers of ancient Karnataka and South India, governing extensive territories from approximately 350 to 1000 CE. These rulers earned distinction from the Eastern Gangas of Odisha (Kalinga), who emerged later in medieval India. The Western Gangas ruled over the region known as Gangavadi, which encompassed present-day districts of Mysore, Hassan, Mandya, Ramanagara, Chamarajanagar, Tumkur, Kolar, and Bangalore in Karnataka state, and at times controlled territories in modern Tamil Nadu (Kongu region) and Andhra Pradesh (Ananthpur district).

Despite their relatively modest territorial extent, the Western Gangas left an indelible mark on South Indian polity, culture, literature, and religion, particularly through their monumental patronage of Jainism and their contributions to early Kannada literature. Their achievements in architecture, religious tolerance, and administrative innovation continue to shape the historical narrative of medieval South India.

ORIGINS AND EARLY HISTORY

Founding and Genealogy

The origin of the Western Ganga Dynasty remains partially shrouded in historical ambiguity, though multiple theories exist regarding their ancestry. Some historians propose that the Gangas were immigrants from northern India, while others contend they were natives of the southern Deccan region. The most prevalent modern theory suggests that the Gangas emerged and consolidated power following the political upheaval caused by Samudra Gupta’s invasion of southern India prior to 350 CE. The Chola confusion and administrative disruption created a power vacuum that ambitious local chieftains exploited to establish their kingdom.

Konganivarman Madhava is recognized as the founder and first king of the dynasty, establishing his capital at Kolar (also called Kuvalala) around 350 CE and ruling for approximately twenty years. The dynasty’s genealogy is described in Sanskrit inscriptions, with early historical clarity emerging from the fourth century onwards. Early inscriptions claim that the Gangas belonged to the Kanvayana lineage (gotra) and Jahnveya connection, though later sources trace them to the Suryavamsa and Ikshvaku dynasties.

Territorial Expansion (4th-6th Centuries)

The early Ganga rulers pursued a strategy of consolidation through both military conquest and matrimonial alliances with neighboring dynasties, particularly the Pallavas, Chalukyas, and Kadambas.

Harivarma (390-410 CE): Consolidated the emerging Ganga kingdom and strategically moved the capital from Kolar to Talakad (Sanskrit: Talavanapura) on the banks of the Kaveri River, approximately 45 km east of Mysore. This strategic relocation contained the growing Kadamba power and facilitated better control of central territories.

Vishmagoppa (410-430 CE): Continued territorial consolidation, securing control over the modern Bangalore, Kolar, and Tumkur districts.

Madhava II (430-469 CE): Expanded Ganga influence further, establishing firmer administrative structures.

Avinita (469-529 CE): Extended Ganga authority into the Kongu region of modern Tamil Nadu by 470 CE and married a Ganga princess to Rajasimha Pandya’s son, establishing peaceful matrimonial bonds that secured the contested region against Pandya encroachment.

MAJOR RULERS AND POLITICAL ACHIEVEMENTS

Durvinita: The Golden Era (529-579 CE)

Durvinita stands as arguably the most successful and accomplished ruler of the Western Ganga Dynasty. His 50-year reign represented a golden era of military achievement, cultural efflorescence, and administrative stability.

Accession and Consolidation: Durvinita’s path to throne contested by his brother, who enlisted Pallava and Kadamba support. However, through military valor and strategic prowess, Durvinita defeated his rival and consolidated power.

Military Achievements:

Successfully defeated multiple Pallava invasions during repeated conflicts with the Pallava kingdom

Battled the Pandyas of Madurai over control of contested Kongu regions, though ultimately sustaining some territorial losses to Pandyan pressure

Expanded Ganga influence through military campaigns while maintaining stability with neighboring powers

Won the title and prestige of a major regional power

Cultural Patronage: Durvinita was an accomplished ruler who patronized Jainism extensively and was known for literary and scholarly pursuits. He is referenced in 9th century Kannada writings (Kavirajamarga of 850 CE) as an early writer of Kannada prose, making him one of the first documented Kannada literary figures.

Post-Durvinita Period and Feudatory Status

Following Durvinita’s reign, the Ganga dynasty experienced a gradual decline in autonomy as larger imperial powers asserted themselves across the Deccan region.

Rise of Badami Chalukyas (553-753 CE): After the Chalukya empire established dominance in the Deccan, the Western Gangas accepted Chalukya overlordship and fought on their behalf against the Pallavas of Kanchi and other rivals.

Rashtrakuta Period (753-973 CE): With the displacement of the Chalukyas by the Rashtrakutas of Manyakheta in 753 CE, the Gangas initially resisted Rashtrakuta overlordship. However, after a century of struggle for autonomy, the Gangas pragmatically accepted Rashtrakuta supremacy.

Strategic Alliance with Rashtrakutas: A significant turning point occurred when Rashtrakuta Emperor Amoghavarsha I (814-877 CE), recognizing the futility of continuous warfare, offered his daughter Chandrabbalabbe in marriage to Ganga prince Butuga I, son of King Ereganga Neetimarga. This matrimonial bond transformed the Gangas into staunch allies of the Rashtrakutas, a position maintained until the Rashtrakuta dynasty’s eventual decline.

Later Rulers and Territorial Expansion (10th Century)

Butuga II (938-961 CE): Ascended the throne with support of Rashtrakuta Amoghavarsha III (whose daughter he married). Butuga II proved instrumental in Rashtrakuta victories during the Battle of Takkolam (949 CE) against the Chola Dynasty. In recognition of this valor, the Rashtrakutas awarded the Gangas extensive territories in the Tungabhadra River valley, significantly expanding their territorial holdings.

Marasimha II Satyavakya (963-975 CE): Continued Rashtrakuta alliance, aiding them in military campaigns against the Gurjara Pratiharas of Central India and the Paramara kings of Malwa.

Rachamalla IV Satyavakya (975-986 CE): Witnessed the rise of significant cultural and religious patronage during his reign, particularly through his minister Chavundaraya.

Rachamalla V (Rakkasaganga) (986-999 CE): Final significant ruler, maintaining Ganga prestige in the declining years before the dynasty’s fall.

CHAVUNDARAYA: MINISTER, WARRIOR, AND SCHOLAR

Chavundaraya (also spelled Chamundaraya, 940-989 CE) represents one of the most remarkable figures in Western Ganga history and medieval South Indian civilization. Unlike the kings themselves, Chavundaraya achieved lasting fame through his multifaceted talents and contributions spanning military command, administration, literature, and religious patronage.

Life and Service

Chavundaraya served as minister and commander under three Western Ganga kings: Marasimha II (963-975), Rachamalla IV (975-986), and Rachamalla V (986-999). He claims descent from the Brahmakshatriya Vamsa (Brahmin converted to Kshatriya caste). The Algodu inscription (Mysore district) and Arani inscription (Mandya district) detail his family genealogy, indicating his father Mabalayya was a subordinate of King Marasimha II.

Military Achievements

With the title Samara Parasuram (“Battle-Rama wielding an axe”), Chavundaraya earned reputation as a valiant military commander. He:

Suppressed civil rebellions and internal disturbances within the Ganga kingdom

Expanded Western Ganga territories through successful military campaigns

Assisted King Rachamalla IV in suppressing a civil war in 975 CE

Maintained military stability during a period of broader Deccan political realignment

Literary and Scholarly Contributions

Chavundaraya’s intellectual legacy proves equally impressive. A devoted Jain, he was influenced by Jain Acharya Nemichandra and Ajitasena Bhattaraka, yet proved himself a universal scholar.

Major Literary Work: In 978 CE, Chavundaraya composed Chavundaraya Purana (also titled Trishasthi Lakshana Mahapurana) in Kannada prose. This work represents one of the earliest existing prose compositions in the Kannada language and achieved significant importance in early Kannada literature.

Content and Significance:

Summarizes Sanskrit texts Adipurana and Uttarapurana (composed by Jinasena and Gunabhadra during Rashtrakuta Amoghavarsha I’s reign)

Narrates legends of twenty-four Jain Tirthankaras, twelve Chakravartins, nine Balabhadras, nine Narayanas, and nine Pratinrarayanas—encompassing narratives of 63 Jain proponents

Written in lucid, accessible Kannada specifically intended for common people

Intentionally avoids complex Jain philosophical doctrines, making spiritual teachings broadly comprehensible

Shows influences from predecessor Adikavi Pampa and contemporary poet Ranna

Sanskrit Works: Beyond Kannada compositions, Chavundaraya authored Caritrāsāra (Character Essence), a Sanskrit work demonstrating his Sanskrit erudition.

Patronage of Scholars: Chavundaraya actively patronized prominent Kannada grammarians Gunavarma and Nagavarma I, as well as celebrated poet Ranna, whose Parusharama Charite may have been composed as eulogy to his patron.

Greatest Achievement: The Gomateshwara Statue

Chavundaraya’s most enduring and celebrated achievement was commissioning the construction of the Bahubali Gomateshwara statue at Shravanabelagola, one of the world’s most magnificent monolithic sculptures and a paramount symbol of Jain heritage.

Construction Details:

Commissioned: 981 CE

Consecrated: 983 CE

Location: Vindhyagiri (Indragiri) Hill, Shravanabelagola, Karnataka

Material: Single block of granite

Height: 57 feet (17.4 meters)

Significance: One of the tallest free-standing monolithic statues in the ancient world

Artistic Classification: Highest achievement of Western Ganga sculptural tradition

Iconographic Features:

Depicts the meditative form of Bahubali (also called Gomateshwara or Kammateswara), revered Jain figure and son of Rishabhanatha (the first Tirthankara)

Represents Kayotsarga (standing meditation) posture, symbolizing profound spiritual discipline

Depicts climbing vines entwined around limbs, symbolizing complete detachment from worldly concerns

Serene facial expression conveys spiritual enlightenment and transcendence

Cultural Significance:

Embodies Jain principles of peace, non-violence, sacrifice of worldly affairs, and simple living

Represents Jainism’s ideals of renunciation and meditative achievement

Marks Shravanabelagola as one of Jainism’s holiest pilgrimage destinations

In 2007, voted first of “Seven Wonders of India” in Times of India poll (49% of votes)

Mahamastakabhisheka Festival: Every twelve years, the grand Mahamastakabhisheka ritual takes place, wherein the statue is ceremonially bathed in milk, saffron, ghee, sugarcane juice, and other sacred substances. This unique festival sustains the statue’s appearance and spiritual significance. The next scheduled Mahamastakabhisheka will occur in 2030.

Chavundaraya Basadi

Beyond the Gomateshwara statue, Chavundaraya commissioned construction of the magnificent Chavundaraya Basadi on Chandragiri Hill in Shravanabelagola during King Marasimha II’s reign (982 CE) and completed by his son Jinadeva. The temple complex represents exceptional Dravidian architectural achievement and houses the idol of Neminatha (the 22nd Tirthankara).

CAPITAL: TALAKAD

Significance and History

Talakad (Sanskrit: Talavanapura, literally “jungle forest city”) served as the Western Ganga capital from approximately 390 CE until the dynasty’s decline around 1000 CE, spanning over six centuries of significance.

Architectural and Religious Importance

Talakad evolved into a major religious and administrative center, hosting numerous Hindu temples, Jain establishments, and administrative structures:

Panchalingas: Five temples symbolizing the five faces of Shiva, lined along the Kaveri River banks

Panchalinga Darshana: Pilgrimage circuit visiting all five temples, undertaken by thousands of devotees

Archaeological Record: Once comprising seven towns and five mathas (monasteries) by the 12th century

Jain Centers: Multiple Jain establishments, particularly significant after the dynasty’s prominence

Decline and Sand Submersion

Talakad experienced a tragic ecological transformation particularly after 1346 CE when Madhavamantri constructed a reservoir. The catastrophic submersion occurred over subsequent centuries:

Formation: Sand dunes began accumulating significantly during the late Vijayanagar period (17th century onwards)

Growth: Dunes rose to heights approaching sixty feet in many locations

Cause: Deforestation along riverbanks, reservoir construction altering water flow, and geographical factors including Mudukuthore hill and slightly elevated watercourse near Mekedatu

Result: Medieval temples and buildings were completely buried, obscuring the site for centuries

Modern Status: Excavations and archaeological work have begun recovering buried monuments, with numerous structures remaining undiscovered beneath sand

Popular Curse Legend: Local tradition attributes Talakad’s devastation to an ancient curse, though archaeological evidence points to ecological and hydrological factors as primary causes.

ADMINISTRATION AND GOVERNANCE

Political Organization

The Western Ganga administration exemplified a sophisticated centralized monarchy with hierarchical governance structures:

Apex Authority: The Ganga Maharaja (king) wielded supreme authority over realm and subjects, supported by a network of feudal lords, ministers, and administrative officials.

Council of Ministers: The inner circle included key officials:

Mahamantri or Sarvadhikari (Prime Minister)

Sachiva or Shribhandari (Treasurer)

Purohita (Chief Priest)

Senapati or Dandanayaka (Military Commander/Supreme General)

Sandhivirgrahi (Foreign Minister/Diplomat)

Administrative Divisions

The kingdom employed a sophisticated multi-tiered administrative structure:

Territorial Division:

Rashtra: District-level division

Visaya/Nadu: Intermediate administrative units (replaced Visaya with Kannada term Nadu from 8th century onwards)

Desa: Village-level divisions

Numerical Designations: Inscriptions reveal complex territorial nomenclature with numerical suffixes. Examples include:

Sindanadu-8000: Indicating either 8,000 villages, revenue yield in monetary units, fighting men, or revenue-paying hamlets

Gangavadi-96000: Major territory, possibly containing 96 Nadus, each with approximately 1,000 villages

Local Administration

Lower-level officials managed day-to-day governance:

Pergades: Superintendents managing artisans, goldsmiths, blacksmiths, and royal household affairs

Nadabova: Local officials

Nalagamiga: Administrative functionaries

Prabhu and Gavunda: Revenue and administrative officers

Judicial System

The Western Gangas maintained a well-defined legal system based on Hindu Dharmashastra principles and customary laws:

Royal courts presided over by king-appointed judges

King served as highest judicial authority

Authority to adjudicate disputes and dispense justice

Land dispute resolution and contract enforcement

Revenue Administration

Tax Collection System: A sophisticated revenue apparatus ensured state income:

Revenue Officials (Mahamandalesvaras or Deshapatis) supervised tax collection in different regions

Maintained records of landownership and assessed taxes accordingly

Responsible for tax compliance and dispute resolution

Ensured equitable resource distribution

Tax Base: Revenue derived from:

Land taxes computed on fertility and agricultural productivity

Commercial taxation on goods and services

Customs and trade duties

MILITARY AND FOREIGN RELATIONS

Military Structure

The Western Gangas maintained organized military forces under appointed commanders (Senapatis and Dandanayakas) responsible for:

Leading armies into battle

Defending strategic fortifications

Maintaining border security

Suppressing internal rebellions

Major Conflicts and Alliances

Early Period: The Gangas engaged in frequent conflicts with the Pallavas of Kanchi, initially as relatively equal powers, later as subordinates to larger overlords.

Pallava Wars: Sripurusha (726-788 CE) achieved notable success against Pallava King Nandivarman Pallavamalla, temporarily bringing Penkulikottai in North Arcot under Ganga control, earning the title Permanadi (conqueror of Penna).

Pandyan Contests: Competition with the Pandyas of Madurai over Kongu region control ended in contested outcomes, though matrimonial alliances maintained regional stability.

Chalukyan Period: After Badami Chalukya dominance, the Gangas served as military allies, fighting against Pallava forces on Chalukyan behalf.

Rashtrakuta Alliance: The strategic marriage alliance with Rashtrakuta Emperor Amoghavarsha I transformed the Gangas into dependable military partners, supporting Rashtrakuta campaigns, most notably the Battle of Takkolam (949 CE) against the ascending Chola power.

Chola Conflict: In the late 10th century, as Chola power surged south of the Kaveri, the Gangas engaged in ultimately unsuccessful resistance, leading to their defeat around 999-1000 CE.

RELIGIOUS AND CULTURAL CONTRIBUTIONS

Jainism Patronage

The Western Gangas earned greatest fame for their extraordinary patronage of Jainism, establishing themselves as foremost supporters of the Jain faith throughout their rule.

General Characteristics:

Most Western Ganga rulers were devout Jains, though maintaining tolerance for other faiths

Constructed magnificent Jain temples and establishments (basadis)

Established Shravanabelagola as premier Jain pilgrimage destination

Commissioned colossal religious sculptures and art works

Supported Jain monastic communities and religious scholarship

Major Jain Monuments

Shravanabelagola Complex:

Became paramount Jain center during and after Western Ganga patronage

Contains fifteen Jain temples (basadis) on Chandragiri Hill

Multiple religious establishments on Vindhyagiri Hill

Center for Jain religious learning and practice

Hosts the Mahamastakabhisheka festival

Remains active pilgrimage center with continuing Jain reverence

Panchakuta Basadi (Kambadahalli):

Located in Mandya District, 18 km from Shravanabelagola

Constructed 900-1000 CE during Western Ganga rule

Represents finest example of Dravidian architecture related to Jain faith

Comprises five garbhagudis (inner sanctums) in clustered arrangement

Central shrine faces north with square superstructure (Brahmachhanda girva-sikhara)

East and west shrines with distinct architectural styles

Four ornate central pillars support navaranga ceiling

Contains attractive decorative carvings and sculptures

Brahmadeva pillar (Manasthambha): 50 feet high octagonal structure with intricate carvings

Protected by Archaeological Survey of India as national monument

Described as “landmark in South India architecture”

Later renovated during Hoysala rule

Chavundaraya Basadi (Shravanabelagola):

Erected 982 CE by Chavundaraya, completed by his son Jinadeva

Represents Dravidian architectural excellence

Contains Neminatha idol flanked by Chauri bearers (possibly installed during Hoysala period)

Underwent 12th-century improvements under Chola rule

Pyramidal shikhara with domical finial exemplifies Chola architectural influence

68 by 36 feet structure with ornamental niches

Largest shrine in Shravanabelagola complex

Known as “Sruta-tirtha” (sacred place of scripture) as venue where 10th-century Jain Acharya Nemichandra composed Gommatsāra

Hindu Patronage

While primarily Jain supporters, the Western Gangas demonstrated religious tolerance and sponsored Hindu temples:

Talakad’s Hindu Heritage:

Capital Talakad contains numerous Shaiva and Vaishnava temples

Panchalingas represent Shaiva religious center

Remains important Hindu pilgrimage destination

Attracts lakhs (hundreds of thousands) of devotees during Panchalinga Darshana

Syncretic Approach: The Gangas successfully maintained Jain-Hindu religious coexistence, with rulers making grants to Brahmanas while firmly supporting Jainism, exemplifying medieval Indian religious pluralism.

LITERATURE AND INTELLECTUAL CONTRIBUTIONS

Early Kannada Literary Development

The Western Ganga period marks the crucial emergence and flowering of Kannada as a literary language distinct from Sanskrit, representing a transformative epoch in South Indian literary history.

Major Kannada Writers and Works

Early Period:

Durvinita (6th century, 529-579 CE): Recognized as early Kannada prose writer, referenced in 850 CE Kavirajamarga

Shivamara II (800 CE): Kannada literary contributions

Flourishing Period:

Gunavarma I (c. 900 CE): Authored Shudraka and Harivamsha in Kannada (works now extinct but referenced in later texts)

Ranna (973 CE): Authored Parusharama Charite, likely eulogy to his patron Chavundaraya; significant Kannada poet

Chavundaraya (978 CE): Chavundaraya Purana (Trishasthi Lakshana Mahapurana)

Early existing Kannada prose work

63 Jain biographical narratives

Composition in accessible Kannada for common people

Deliberately simplified religious content

Shows influences from Adikavi Pampa and Ranna

Nagavarma I (990 CE): Kannada grammatical and literary works

Sanskrit Contributions

Concurrent with Kannada development, the Gangas patronized Sanskrit literary production, particularly on religious and philosophical subjects.

Writing System and Language Policy

Bilingual Practice:

Early period emphasized Sanskrit copper-plate charters with formal genealogies

Second phase (725-1000 CE) witnessed dramatic shift toward Kannada

Lithic (stone) inscriptions in Kannada increasingly outnumbered Sanskrit copper plates

Reflects Jain patronage of Kannada as medium for spreading religious teachings

Encouragement of Literacy: The dynasty fostered scholarly learning and manuscript preservation, establishing their court as intellectual hub.

Literary Content

Beyond religious works, Western Ganga-period literature encompassed diverse subjects:

Religious and philosophical compositions

Jain Tirthankara biographies and legends

Elephant management treatises

Grammatical and linguistic works

Poetry and epic compositions

ECONOMY AND TRADE

Agricultural Foundation

Agriculture formed the fundamental economic base of the Western Ganga kingdom:

Geographical Regions:

Malnad (Western Ghats region): Produced paddy, betel leaves, cardamom, pepper

Plains (Bayaluseemae): Rice and millet cultivation

Semi-malnad: Buffer region with rolling hills

Irrigation and Agricultural Technology

The Western Gangas invested significantly in irrigation infrastructure:

Constructed and maintained irrigation tanks

Advanced water management systems

Enhanced agricultural productivity through engineering

Facilitated agrarian expansion

Trade and Commerce

Regional Trade Networks:

Active engagement in inter-regional commerce

Trade routes connecting various urban centers

Exchange of manufactured goods and agricultural products

Urban Centers:

Perura: Important commercial center

Kovalalapura (Kolar): Early Ganga capital region

Manyapura: Northern commercial hub

Talavanapura (Talakad): Capital city serving administrative and commercial functions

Merchants and Guilds:

Organized merchant communities

Guild-based commercial structures

Commercial regulation and taxation

Revenue System

Multiple Revenue Sources:

Land revenue (primary source)

Commercial taxation on goods and services

Customs duties on trade

Special taxes on particular occupations

Temple donations and religious contributions

State Expenditure:

Administrative salaries

Military maintenance

Temple and religious establishment support

Public works and infrastructure development

Court and palace maintenance

Impact on Urbanization

Recent historical analysis demonstrates that Western Ganga rule contributed significantly to urbanization processes:

State promoted agrarian expansion

Created new revenue collection networks

Supported religious establishments generating demand for goods and services

Facilitated merchant community expansion

Developed urban centers through state patronage

Historiographical Correction: Earlier “Indian Feudalism” model scholars incorrectly characterized the Western Ganga period as economically declining. Modern research reveals robust trade, commerce expansion, and urbanization during their rule, contradicting earlier assumptions.

DECLINE AND FALL

Late 10th Century Political Changes

The final century of Western Ganga rule witnessed dramatic Deccan political transformation:

Contemporary Developments:

Rashtrakuta Empire: Declined and eventually fell to the emerging Western Chalukya Empire north of the Tungabhadra River

Chola Revival: The Chola Dynasty renewed its power south of the Kaveri River, expanding northward into Western Ganga territories

Power Vacuum: Regional balance shifted decisively against the Gangas

Defeat and Termination

Chola Victory (999-1000 CE): The Western Gangas suffered decisive military defeat at the hands of the expanding Chola Dynasty around 999-1000 CE. Despite their long history and cultural achievements, military pressure from the ascendant Cholas proved insurmountable. The dynasty’s rule effectively terminated, ending approximately 650 years of Ganga sovereignty.

Talakad Rename: After conquest, the city was renamed Rajarajapura in honor of the Chola victor.

Subsequent History

Hoysala Conquest (1117 CE): Over a century later, the renowned Hoysala king Vishnuvardhana conquered Talakad from Chola control and assumed the title Talakadugonda (“Conqueror of Talakad”). He commissioned the construction of the Keerthinarayana temple to commemorate this military achievement.

Physical Decline: Talakad gradually declined as a major urban center. Beginning in the 17th century, sand dunes increasingly encroached upon the city, eventually burying medieval temples and structures beneath extensive sand deposits extending over a mile, creating the dramatic archaeological site visible today.

LEGACY AND HISTORICAL SIGNIFICANCE

Political Legacy

The Western Gangas established the first indigenous state in southern Karnataka, demonstrating that regional powers could maintain sophisticated governance, administer complex administrative structures, and contribute to broader South Indian political developments despite subordination to larger empires. Their administrative innovations influenced subsequent dynasties.

Cultural Achievements

Their patronage catalyzed the emergence of Kannada as a literary language, moving beyond Sanskrit’s monopoly and facilitating vernacular literary development. The monuments they commissioned remain among South India’s finest architectural achievements, accessible to modern visitors and scholars.

Religious Contributions

The Western Gangas transformed Shravanabelagola into Jainism’s premier pilgrimage center and created the Gomateshwara statue—among the world’s most impressive monolithic sculptures. Their Jain temples at Kambadahalli and other sites preserve architectural traditions and spiritual heritage.

Administrative Innovation

Their hierarchical governance structure, revenue collection systems, and administrative divisions influenced later South Indian administration. The sophisticated organization of territories into Nadus with revenue calculations, judicial systems, and minister councils established models followed by subsequent dynasties.

Scholarly Heritage

Early Kannada literary works composed under Western Ganga patronage established literary traditions continuing to the present. The preservation of texts like Chavundaraya Purana maintained intellectual continuity linking early medieval to later Kannada literature.

Historiographical Importance

Recent scholarly reassessment has elevated Western Ganga significance within early medieval South Indian historiography. They demonstrate that:

Indigenous state-building occurred without requiring external conquest or colonization

Economic development and urbanization progressed during their rule, contrary to earlier feudal decline theories

Religious pluralism and cultural heterogeneity characterized medieval Indian society

Administrative sophistication existed in pre-colonial Indian political systems

CONCLUSION

The Western Ganga Dynasty, despite their historical eclipse by more powerful empires, represents a crucial chapter in South Indian history. Their 650-year rule witnessed the development of indigenous Karnataka state structures, the flowering of early Kannada literature, and the creation of enduring Jain religious monuments. Through figures like Chavundaraya and rulers like Durvinita, they demonstrated that regional powers could achieve cultural and intellectual distinction while navigating complex political circumstances.

The Gomateshwara statue at Shravanabelagola and the temples of Kambadahalli stand as visible reminders of their legacy. Modern Talakad, though partially buried beneath sand, continues revealing secrets of their capital city. Their administrative systems influenced subsequent dynasties, and their literary patronage shaped Kannada’s development as a language of intellectual and religious expression.

The Western Gangas remind historians that historical significance extends beyond military conquest and territorial extent. Cultural patronage, administrative sophistication, religious tolerance, and intellectual contribution constitute equally important measures of a civilization’s lasting impact on human history. In these dimensions, the Western Gangas stand among South India’s most distinguished dynasties.

KEY POINTS:

Chronology:

Founded: c. 350 CE (Konganivarman)

Peak: 529-579 CE (Durvinita); 938-975 CE (Butuga II, Marasimha II)

Decline: 10th century; ended c. 999-1000 CE

Capitals: Kolar (350-390 CE) → Talakad (390-1000 CE)

Region: Gangavadi (Mysore, Hassan, Mandya, Tumkur, Kolar, Bangalore)

Key Rulers: Konganivarman, Harivarma, Durvinita, Sripurusha, Butuga II, Marasimha II, Rachamalla IV

Important Figure: Chavundaraya (940-989 CE) – Minister, commander, author

Cultural Contributions:

Gomateshwara statue (57 feet, 983 CE)

Panchakuta Basadi, Kambadahalli

Early Kannada literature (Chavundaraya Purana, 978 CE)

Jain patronage and monuments

Political Status:

Independent (350-550 CE) → Subordinate to Chalukyas → Subordinate to Rashtrakutas (allies) → Defeated by Cholas (1000 CE)

Administration: Centralized monarchy, hierarchical divisions (Rashtra, Nadu/Visaya, Desa), council of ministers

Economy: Agriculture-based, trade networks, urban centers

Decline: Defeated by Cholas around 999-1000 CE; later ruled by Hoysalas

also read: Early Medieval India

Discover more from Simplified UPSC

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.