Basic Structure of the Constitution

Contents

Basic Structure of the Constitution: Comprehensive Study Notes

Introduction

The Basic Structure doctrine represents one of the most significant constitutional principles in Indian jurisprudence. It establishes that while Parliament possesses the power to amend the Constitution under Article 368, this power is not absolute. Certain fundamental features—collectively termed the “basic structure”—are inviolable and cannot be altered or destroyed through constitutional amendments, even by a super-majority in Parliament.

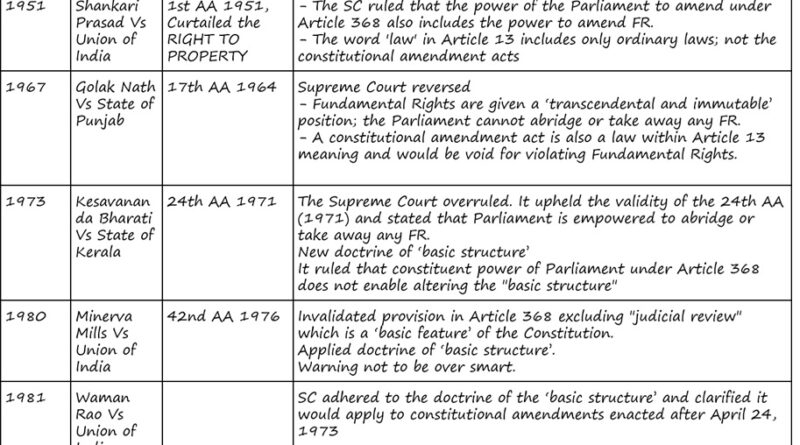

Evolution of the Doctrine: Landmark Cases

1. Shankari Prasad v. Union of India (1951)

Facts: The constitutional validity of the First Amendment Act (1951), which curtailed the right to property, was challenged on the ground that it violated fundamental rights.

Supreme Court’s Ruling:

Parliament’s amending power under Article 368 includes the power to amend Fundamental Rights

The word “law” in Article 13 refers only to ordinary legislation, not constitutional amendment acts

Constitutional amendments cannot be challenged under Article 13

Therefore, Parliament can abridge or take away any Fundamental Right through constitutional amendment

Significance: Established Parliament’s plenary power to amend the Constitution without judicial intervention.

2. Golak Nath v. State of Punjab (1967)

Facts: The constitutional validity of the Seventeenth Amendment Act (1964), which inserted certain state acts in the Ninth Schedule, was challenged.

Supreme Court’s Ruling:

Overturned Shankari Prasad judgment

Fundamental Rights are given a “transcendental and immutable” position

Parliament cannot abridge or take away Fundamental Rights

A constitutional amendment act is also a “law” within Article 13

Any amendment violating Fundamental Rights would be void under Article 13

Significance: Protected Fundamental Rights from parliamentary amendment but was itself later reversed.

3. 24th Constitutional Amendment Act (1971)

Parliamentary Response:

Parliament amended Articles 13 and 368 in response to Golak Nath judgment

Declared that Parliament has the power to abridge or take away any Fundamental Right under Article 368

Such amendment would not be considered a “law” under Article 13

Impact: Restored Parliament’s amending power but invited further judicial intervention.

4. Kesavananda Bharati v. State of Kerala (1973) – The Landmark Judgment

Facts: Constitutional validity of the 24th Amendment Act (1971) was challenged.

Key Features:

Largest Constitution Bench: 13 judges (record for that time)

Decision: 7-6 majority

Duration: 68 days of hearing

Judgment volume: One complete volume in Supreme Court Cases

Supreme Court’s Historic Ruling:

Upheld the 24th Amendment Act – Parliament can amend Fundamental Rights

Introduced the Basic Structure Doctrine – Parliament’s amending power under Article 368 is not absolute

Fundamental Principle: The constituent power of Parliament does not enable it to alter the “basic structure” of the Constitution

Consequence: Parliament cannot destroy or fundamentally alter those elements that constitute the basic features of the Constitution

Justice Hans Raj Khanna’s Reasoning:

The power to amend is NOT the power to destroy

The Constitution has certain immutable characteristics that reflect its foundational values

The preamble is an intrinsic part of the basic structure

The golden triangle consisting of Articles 14, 19, and 21 forms the basis of the Indian legal system

Significance:

Landmark jurisprudence establishing limits on constitutional amendment power

Introduced the doctrine that would guide constitutional interpretation for decades

Protected the core principles of the Constitution from majoritarian destruction

5. 42nd Constitutional Amendment Act (1976)

Context: Parliamentary response to Kesavananda Bharati judgment during the Emergency period.

Major Changes:

Amended Article 368

Declared that there is NO limitation on Parliament’s constituent power

No amendment can be questioned in any court on any ground

Cannot be challenged for violation of Fundamental Rights

Expanded Article 31C to protect all Directive Principles

Attempt: To nullify the basic structure doctrine and grant absolute amending power to Parliament.

6. Minerva Mills Ltd. v. Union of India (1980)

Facts: Validity of provisions in the 42nd Amendment restricting judicial review was challenged.

Supreme Court’s Landmark Ruling:

Struck Down the 42nd Amendment provisions that excluded judicial review

Reaffirmed the Basic Structure Doctrine

Articulated the Key Principle:

“Since the Constitution had conferred a limited amending power on the Parliament, the Parliament cannot under the exercise of that limited power enlarge that very power into an absolute power. Indeed, a limited amending power is one of the basic features of the Constitution and, therefore, the limitations on that power cannot be destroyed.”

The Doctrine: A donee of a limited power cannot convert that power into an unlimited one

New Elements Added to Basic Structure:

Judicial review (power of courts to scrutinize constitutional amendments)

Balance between Fundamental Rights and Directive Principles

Significance:

Established that judicial review itself is a basic feature

Parliament cannot use Article 368 to remove the Court’s power to judge constitutional amendments

Confirmed that the Constitution is supreme, not Parliament

7. Waman Rao v. Union of India (1981)

Facts: Challenge to the validity of certain constitutional amendments under the basic structure doctrine.

Supreme Court’s Ruling:

Reaffirmed adherence to the basic structure doctrine

Critical Clarification: The doctrine would apply to constitutional amendments enacted AFTER April 24, 1973 (date of Kesavananda Bharati judgment)

Earlier amendments made before this date would not be subjected to basic structure review

Significance: Determined the temporal application of the doctrine, providing clarity on retrospectivity.

8. S.R. Bommai v. Union of India (1994)

Facts: Validity of President’s Rule in several states under Article 356 was challenged during a constitutional crisis involving frequent dismissals of opposition-led state governments.

Nine-Judge Bench Ruling:

Scope of Article 356:

Limited power for extraordinary circumstances

Cannot be used for political convenience

Requires objective material and cannot be mala fide

Federalism as Basic Structure:

State governments are NOT subordinate to the center

Federal balance is a core constitutional feature

Established principle of “Cooperative Federalism”

Secularism as Basic Structure:

Established that secularism is part of the basic structure

President’s Rule can be imposed if a state violates secular principles

Requires clear evidence of communal governance

Judicial Review of Proclamations:

Court can review Article 356 proclamations

Presidential power is not absolute and is subject to constitutional limits

Outcomes:

Struck down President’s Rule in Karnataka, Meghalaya, and Nagaland as unconstitutional

Upheld proclamations in other states where breakdown was evident

Significance:

Reinforced federalism as inviolable feature

Expanded application of basic structure doctrine

Established checks on executive power

Recognized secularism as core constitutional principle

9. Indra Sawhney v. Union of India (1992) – Mandal Commission Case

Facts: Constitutional validity of 27% reservation for OBCs was challenged.

Nine-Judge Bench Ruling:

Upheld OBC reservations based on social and educational backwardness

50% Ceiling: Total reservations cannot exceed 50% of available positions

Creamy Layer Concept: Excluded wealthier members of backward communities from reservation benefits

Scope of Application: Reservations apply at initial appointments, not promotions (later modified by 77th Amendment)

Basic Structure Elements Affirmed:

Principle of equality

Social and economic justice

Significance:

Applied basic structure doctrine to reservation jurisprudence

Balanced equality with compensatory justice

Established flexibility in basic structure interpretation

10. Janhit Abhiyan v. Union of India (2023)

Facts: Constitutional validity of 103rd Amendment introducing 10% EWS (Economically Weaker Sections) reservation was challenged on basic structure grounds.

Five-Judge Constitutional Bench (3:2 Majority):

Upheld the 103rd Amendment introducing 10% EWS reservation

Key Findings:

Reservations based exclusively on economic criteria are constitutionally permissible

Economic backwardness is a valid classification ground

The 50% reservation ceiling is NOT absolute and can be exceeded for compelling reasons

Reasonable classification between “economically weaker sections” and existing beneficiaries (SCs, STs, OBCs) is valid

Principle Established:

“Just as equals cannot be treated unequally, unequals also cannot be treated equally”

Basic Structure Application:

Principle of equality remains protected

Economic justice (from Preamble and Articles 38, 46) justified the amendment

The amendment did not destroy the basic structure

Dissent (2 Judges):

Argued that exceeding the 50% ceiling and exclusion of existing beneficiaries violated basic structure principles

Significance:

Demonstrated flexibility of basic structure doctrine

Recognized economic justice as core constitutional value

Showed Court’s pragmatic interpretation of equality

11. Property Owners Assn. v. State of Maharashtra (2024)

Facts: Challenge to Maharashtra Housing and Area Development Act under Articles 14 and 19; protection claimed under Article 31C.

Nine-Judge Bench Ruling (November 2024):

Doctrine of Revival: When a constitutional amendment is struck down, the original provision automatically revives

Continuity Principle: The Court rejected the “pen and ink theory” arguing that original text ceases to exist

Article 31C Status:

Unamended Article 31C survives and continues in force

Protects laws furthering Articles 39(b) and (c) from challenge under Articles 14 and 19

Reasoning:

Basic structure doctrine ensures continuity and coherence of constitutional framework

Automatic revival prevents legal vacuum

The NJAC case and similar precedents support this approach

Flexibility Clause:

In cases where evidence suggests legislature would have repealed original text independently, courts can effect the repeal despite invalidating new text

Significance:

Strengthened constitutional continuity principle

Protected welfare legislation through Article 31C

Applied basic structure to ensure stable constitutional framework

12. Uttar Pradesh Board of Madrassa Education Act Challenge (2024)

Context: Allahabad High Court struck down the UP Madrasa Education Board Act, 2004 for violating secularism.

Supreme Court’s Three-Judge Bench Ruling (November 2024):

Basic Structure and Secularism:

Agreed that secularism is part of basic structure

Clarified that a law is unconstitutional on secularism grounds ONLY if it explicitly violates secularism-related constitutional provisions

Mere contradiction with broad secularism principles does not render law unconstitutional

Test Applied:

The Act does not violate Articles related to secularism

The State can regulate educational standards in minority institutions

Article 28(3) protection ensures students cannot be forced into religious instruction

Significant Clarification:

The basic structure doctrine CANNOT be applied to challenge the validity of ordinary laws

Applied directly to constitutional amendments and extraordinary situations

Significance:

Limited scope of basic structure doctrine application

Clarified that secularism challenge requires explicit constitutional violation

Maintained distinction between amendment review and law validity

13. Article 31C and Preamble Amendment (2024)

Supreme Court’s Ruling (November 2024):

Preamble Amendability:

Parliament has power to amend the Preamble under Article 368

Preamble is part and parcel of the Constitution, not separate

42nd Amendment Validation:

The 42nd Amendment that inserted “socialist” and “secular” in the Preamble has been subjected to extensive judicial review

The Court acknowledged Parliament’s intervention and constitutional legitimacy

Will not nullify Parliament’s Emergency-period actions without compelling reason

Significance:

Affirmed that Preamble, despite fundamental importance, is amendable

Showed judicial deference to legislative judgment in specific circumstances

Elements of the Basic Structure

The Supreme Court, though avoiding a definitive and closed list, has identified the following elements as constituting the “basic structure” of the Constitution:

Foundational Principles:

Supremacy of the Constitution – Constitution is the supreme law; no law or amendment can override it

Sovereign, Democratic, and Republican Nature – India is a sovereign democratic republic

Secular Character – State has no official religion; equal treatment of all religions

Structural Elements:

Separation of Powers – Division of legislative, executive, and judicial functions with checks and balances

Federal Character – Division of powers between Union and States; state autonomy and cooperative federalism

Parliamentary System – Democratic governance through elected representatives; Cabinet accountability to Parliament

Independence of Judiciary – Judicial autonomy in decision-making; protection from executive/legislative interference

Rights and Justice:

Judicial Review – Power of courts to scrutinize laws and amendments for constitutionality

Fundamental Rights – Protected rights of individuals (especially those in Articles 14, 19, 21)

Freedom and Dignity of the Individual – Core human rights protection

Rule of Law – Government operates within constitutional bounds; equal application of law

Democratic Principles:

Free and Fair Elections – Democratic legitimacy based on periodic, transparent elections

Principle of Equality – No discrimination on grounds of religion, caste, gender, etc. (Article 14)

Principle of Reasonableness – Laws must be reasonable and not arbitrary

Welfare and Justice:

Welfare State (Socio-Economic Justice) – State responsibility for social and economic well-being

Directive Principles of State Policy – Socio-economic aspirations and goals of the nation

Balance and Limitation:

Harmony and Balance between Fundamental Rights and Directive Principles – Both Parts III and IV must coexist and support each other

Limited Power of Parliament to Amend the Constitution – Parliament’s amending power itself is limited and cannot be converted into absolute power

Judicial Powers:

Powers of the Supreme Court under Articles 32, 136, 141, and 142 – Protective jurisdiction and remedial powers

Key Principles Derived from Basic Structure Doctrine

1. The Doctrine of Limited Amendment Power

Parliament can amend any part of Constitution (including Fundamental Rights)

But amendments cannot alter or destroy the basic structure

The power to amend is not the power to destroy

2. Judicial Review of Constitutional Amendments

Courts can scrutinize constitutional amendments for validity

Even amendments cannot override the basic structure

Judicial review is itself a basic feature and cannot be removed

3. Temporal Application

Basic structure doctrine applies to amendments after April 24, 1973 (Kesavananda date)

Earlier amendments (before this date) generally not subjected to basic structure review (except in specific circumstances)

4. Case-by-Case Determination

No exhaustive definition of basic structure

Each feature is determined through judicial interpretation

Different judges may have varying views on what constitutes basic structure

5. Flexibility and Evolution

Basic structure doctrine is not static

New elements can be recognized as society and constitutional interpretation evolve

The doctrine balances protection with flexibility

6. Hierarchy of Constitutional Principles

Basic structure principles are hierarchically superior to non-basic elements

A conflict between basic and non-basic features resolves in favor of basic structure

Significance of the Basic Structure Doctrine

1. Protection of Constitutional Identity

Preserves the fundamental character and identity of the Constitution

Prevents majoritarian destruction of constitutional values

Protects minority rights and democratic principles

2. Limitation on Political Power

Checks arbitrary use of amendment power for political gains

Prevents governments from using super-majority to dismantle democracy

Ensures constitutional amendments serve nation-building, not political convenience

3. Judicial Role in Constitutional Governance

Establishes courts as custodians of constitutional values

Grants judicial review over amendments

Balances between legislative supremacy and constitutional supremacy

4. Constitutional Continuity and Stability

Ensures constitutional framework remains coherent and stable

Prevents fragmentation through repeated fundamental amendments

Maintains constitutional trust and legitimacy

5. Democratic Safeguard

Protects democratic institutions and processes from dismantling

Ensures periodic elections and civilian rule

Guards against authoritarian constitutional change

Criticisms and Challenges

1. Subjectivity and Judicial Overreach

Different judges define basic structure differently

Raises concerns about judicial activism

Gives unelected judges power to override elected Parliament

2. Lack of Clear Definition

No exhaustive list provided by courts

Case-by-case determination creates uncertainty

Ambiguity in application and scope

3. Conflict with Separation of Powers

Violates strict separation of powers principle

Judiciary interferes in legislative amendment power

Creates tripartite tension in constitutional governance

4. Criticism of Emergency Period Application

Some argue doctrine was unduly invoked during 1975-1977 Emergency

Courts faced pressure to validate or invalidate Emergency amendments

Political circumstances influenced judicial interpretation

5. Practical Implementation Issues

Difficulty in determining when amendments violate basic structure

Different benches may reach different conclusions

Creates scope for strategic litigation

Application in Practice: Recent Trends (2023-2025)

Narrower Scope Application:

Recent judgments suggest courts apply basic structure doctrine more conservatively

Clear violation required, not merely inconsistency with basic principles

Courts show deference to Parliament’s legislative judgment in certain areas

Specific Sectoral Applications:

Reservation Policy: Flexibility shown in economic criteria reservation

Welfare Legislation: Article 31C protection for welfare laws

Fundamental Rights: Continued protection but with reasonable restrictions allowed

Secularism: Requires explicit violation of constitutional provisions, not general inconsistency

Emerging Principles:

Doctrine of Revival: Original provisions revive when amendments struck down

Composite legislative intent: Courts respect Parliament’s overall legislative purpose

Proportionality Test: Amendments must be proportionate to their objectives

Conclusion

The Basic Structure doctrine represents a sophisticated constitutional principle balancing competing values in Indian democracy:

Parliamentary sovereignty with constitutional supremacy

Majoritarian will with minority rights protection

Democratic flexibility with constitutional permanence

Legislative power with judicial review

The doctrine has evolved from its 1973 inception in Kesavananda Bharati to become a cornerstone of Indian constitutional jurisprudence. Recent judgments demonstrate both its enduring importance and its contextual application, as courts navigate the tension between respecting legislative power and protecting foundational constitutional values.

For UPSC aspirants and constitutional scholars, the basic structure doctrine represents the intersection of constitutional law, political philosophy, and judicial statesmanship—making it essential for understanding modern Indian constitutional governance.

Important Timeline

| Year | Case | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| 1951 | Shankari Prasad | Parliament can amend Fundamental Rights |

| 1967 | Golak Nath | Fundamental Rights not amendable |

| 1971 | 24th Amendment | Parliament restores amending power |

| 1973 | Kesavananda Bharati | Basic Structure Doctrine introduced |

| 1976 | 42nd Amendment | Parliament attempts absolute power |

| 1980 | Minerva Mills | Judicial review is basic feature |

| 1981 | Waman Rao | Doctrine applies post-April 1973 |

| 1992 | Indra Sawhney | Applied to reservation jurisprudence |

| 1994 | S.R. Bommai | Federalism and secularism as basic features |

| 2023 | Janhit Abhiyan | Economic criterion reservation upheld |

| 2024 | Property Owners Assn. | Doctrine of revival affirmed |

| 2024 | UP Madrasa Education Act | Basic structure doctrine limits clarified |

Discover more from Simplified UPSC

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.